Passion Player

Clapperboard / Philip Sindall

Passion Player

Clapperboard / Philip Sindall

BY: David A. Ellis

Camera operator Philip Sindall was born in London in 1953. As a young child his parents bought him a simple stills camera. Before long he was mixing up chemicals in his mother’s kitchen and using it as a darkroom, printing pictures to show at his local photographic society.

Dreams of becoming a professional stills photographer rapidly changed direction when, aged 15 he saw 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film completely blew him away, and after seeing it five times, he knew cinematography was his future.

In 1973 he attended Harrow College of Technology and Art, to study film production, before securing a post as an assistant cameraman with the BBC. Working with cameraman Philip Bonham-Carter, on documentaries and music and arts, taught him to think quickly on his feet and how to handle sometimes-delicate situations.

Whilst shooting a documentary about the making of the film Gandhi, Sindall felt persuaded to work in features as an operator. He says, “Witnessing the monumental and emotional funeral scene, I watched the crew in action; this was definitely something I wanted to be a part of. To pursue this further I would have to leave the BBC, which wasn’t easy, as I loved the Ealing Film Unit with its incredible cross section of work and huge pool of inspiring cameramen.”

Sindall left in 1984 when the world of MTV was exploding: he started focus-pulling on pop videos for George Michael, Simply Red, The Human League, Ozzy Osbourne and hundreds more. During this time he met a number of DPs, including former BBC man Mike Southon BSC. He pulled focus for him on the feature Captive and later went on to operate for him on six films. Sindall says he will always be extremely grateful to Southon for, “putting faith in me and giving me that all-important break as an operator.”

Southon said: “Philip first operated for me on Elphida a one-hour drama for C4. What was apparent from day one was how natural he was, both with the way he could dance with the camera, whether it was handheld or on the doll, and in the way he listened and interacted with Tundi Ikoli, our director, in his quiet unassuming way. He also immersed himself in achieving what the DP wanted from the frame. I've always trusted him as second set of cinematographic eyes. He immerses himself in achieving what the DP wants from the frame. His punctilious note taking of every shot including position, lens and brief sketches of the frame, must make his copies of the scripts of the copious movies he has worked on valuable source material for anyone analysing what has been shot, compared to what finishes up in the movie. On a personal level a nicer guy you'd be hard to find, and I consider him a friend as well as an esteemed colleague.”

So what advice would Sindall give to aspiring camera operators? “Use your stills camera, experiment with composition and your lens choice. Although shooting stills isn’t quite the same as shooting moving pictures, it’s an excellent place to start. Watch as many films as you can from as many genres as possible and most importantly, spend time with an editor in the cutting room. It’s a fantastic place to see sequences constructed and how those shots you’ve beautifully framed don’t necessarily always cut together,” he said.

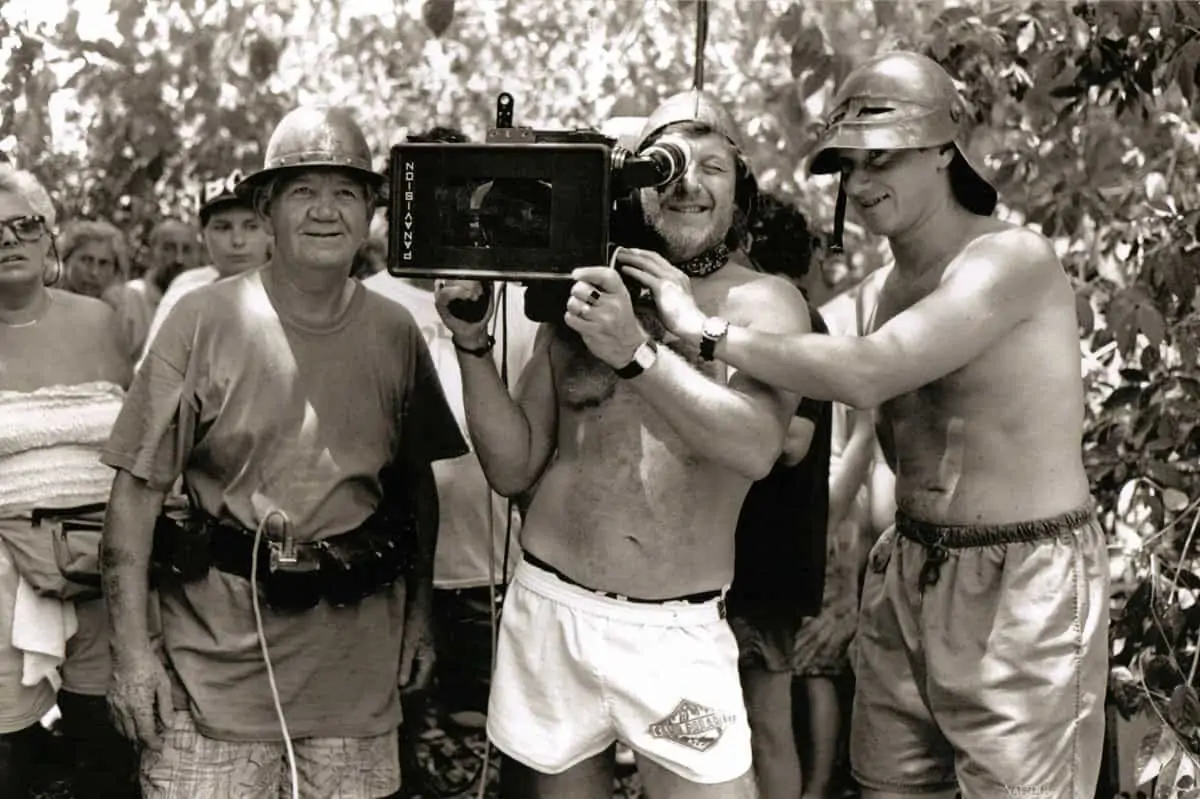

Asked about his favourite films, he replied, “It’s difficult to choose because I’ve been very fortunate to have been part of more than my fair share. Paperhouse was my first feature with Mike Southon, and as such will always have a place in my heart. The first shot was on a python crane mounted on top of a 20-foot tower and I still remember to this day, the buzz I felt on the first take.

“I have always enjoyed working with Michael Coulter BSC. One of the five films we collaborated on was Sense And Sensibility, directed by Ang Lee, who bravely took on this very quintessential English novel with amazing gusto. It starred actress and writer Emma Thompson, who permeates amazing warmth around the entire set. I was also lucky enough to work with her on the two Nanny McPhee films.

“Shakespeare In Love had an amazing cast plus DP Richard Greatrex and director John Madden who both made it an incredibly enjoyable experience. It won the Oscar and luckily for me the BSC Operators’ Award that year. Another is Elizabeth with Remi Adefarasin OBE BSC, a wonderful man, who produced its amazing images and rightly received the BAFTA for Best Cinematography. The film also had an array of talented actors, including Sir Richard Attenborough. Without knowing, it was he who initially persuaded me to be an operator when I saw him working on Gandhi. He was one of the most charming people I’ve ever met. Director Shekhar Kapur had this incredible talent of making the script leap off the page. He could translate his vision to you in a very different way to anyone I’d worked with before, which then inspired one to find the right photographic images for the script.

"Many of the films I have worked on are about people’s lives and emotions and the difficult choices that sometimes we all have to make, portraying that is something which appeals to me."

- Philip Sindall

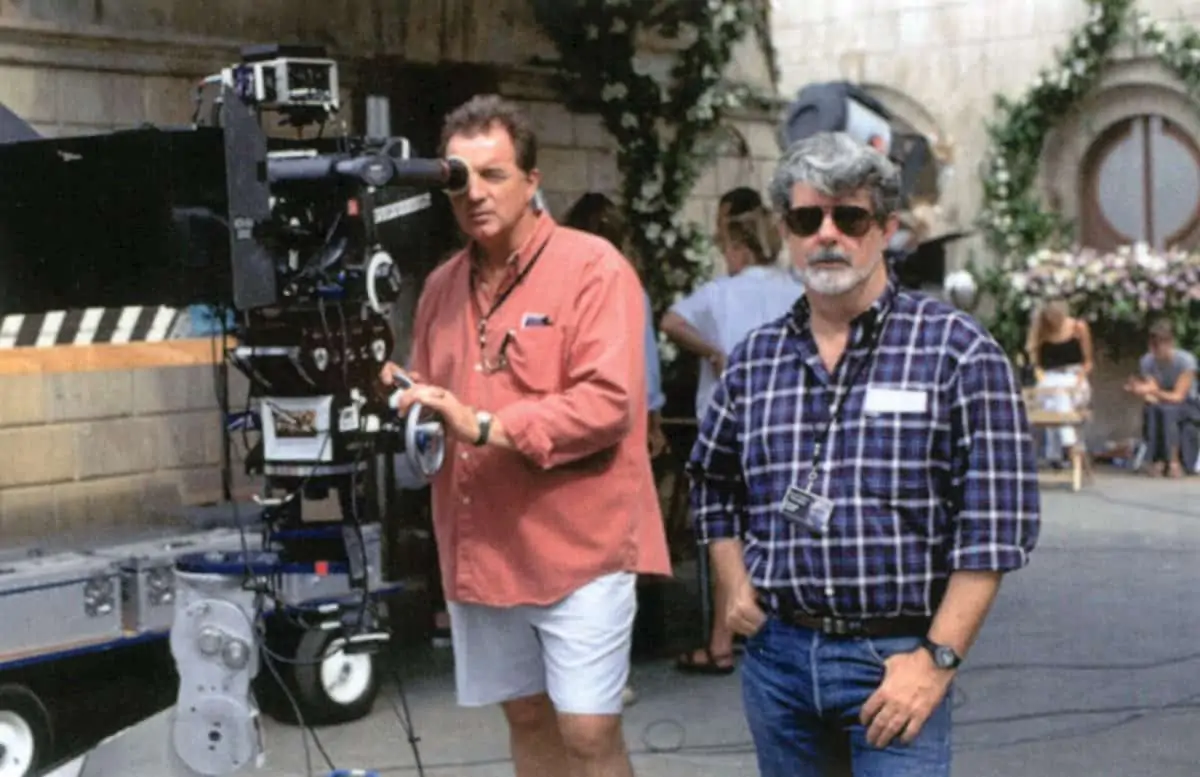

“As I once heard Freddie Francis BSC say: ‘There’s good photography, bad photography and the right photography.’ That’s something I have always tried to bring to my operating. Mama Mia had a lot of complex dance sequences, skilfully directed by Phylida Lloyd, who knew the show inside out, having been with it since its inception. Haris Zambarloukos BSC did an incredible job of making our tavern, hillside and several interiors on Pinewood 007 stage blend in with the exteriors, shot on the Greek Islands.”

Speaking about Sindall, Zambaloukos said, “Philip is an absolute professional and one of the most dedicated and conscientious operators out there, but what’s unique about Phil is his method of preparation. He keeps a diary and notebook containing ideas and thoughts about blocking and conversations that have been discussed in prep. It also helped that he had a good musical background. It’s evident in some of the crane shots, how in tune the camera is to the songs.”

Sindall says, “If I had to choose one film it would be The Hours, because of the complexity. It was shot over a year in four sections because of artists’ availability, with three separate stories set in three time zones, and yet constantly weaving in and out of each other, as the story unfolded. I loved the experience of designing the shots with Seamus McGarvey BSC ASC and director Stephen Daldry and how to construct it over that long period of time. I am very proud of the finished film, it’s a very emotional piece of work.”

He talks of having been very lucky in the business speaking highly of the cinematographers and crew he has worked with; only wishing there was space to mention them all and their constant support that every operator needs.

“Many of the films I have worked on are about people’s lives and emotions and the difficult choices that sometimes we all have to make,” said Sindall. “Portraying that is something which appeals to me.”

Did he ever consider becoming a cinematographer? “I have thought about it. I‘ve often lit sequences where extra footage is required, after the film’s been edited and the original DP isn’t available for the re-shoots. Personally, I always saw the natural progression was to direct, but I never really wanted to make that giant leap. At the end of the day, I just love being behind the camera and working with actors. I so enjoy framing the image and telling the story.”

As well as features, Sindall has done a lot of television work, and is currently working on Downton Abbey. He is a board member of the Association of Camera Operators and also teaches part time at the MET Film School in Ealing, where he first started out with the BBC in 1976.

He said, “It’s a wonderful thing to be able to help future filmmakers find their voice,” which is also something he is helping the ACO to do, by organising screening events with operators talking about their experiences.