Cinematographer Trevor Forrest discusses combining the Millennium DXL camera with Primo 70 optics for the series Tell Me Your Secrets.

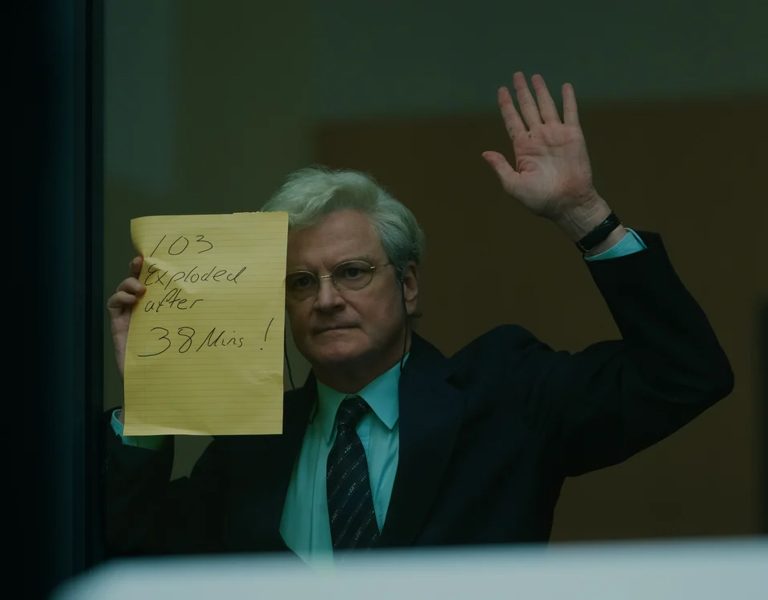

The 10-episode series Tell Me Your Secrets interweaves the stories of three characters whose troubled pasts have set their moral compasses adrift and their destinies on a collision course. Following a stint in prison that stemmed from her relationship with a serial killer, Karen (Lily Rabe) has been placed in witness protection and given the name Emma. Meanwhile, in a no-holds-barred push to find her long-missing and likely deceased daughter, Mary (Amy Brenneman) sets John (Hamish Linklater) on a mission to unearth Karen’s whereabouts — an assignment that forces him to navigate between his equal desires to atone for his sordid past and give in to his baser criminal instincts.

“Lily was really playing two people, so you have two portraits of the same person, which was our entry point into the psychological thriller we had in our hands,” says cinematographer Trevor Forrest, who shared cinematography duties on the pilot with Denis Lenoir ASC AFC. “In witness protection, she has a home, but it’s not her home. She can’t be herself, so it becomes another type of prison. That was really exciting to play with.”

Working with Panavision New Orleans to source a Millennium DXL camera package and Primo 70 large-format lenses, Forrest and John Conroy, ISC alternated the remainder of the series, with Forrest handling the even-numbered episodes and Conroy tackling the rest. “Shooting large format with the DXL was great,” Forrest reflects, “because we could capture these amazing landscapes that feel epic — we shot T11 on the landscapes, with deep focus to convey the world of the swamps and the thundery skies — but then we could bring the camera down, put it on a shoulder and sit on a stool in front of Lily, and we had this whole landscape of her face to look at.”

Principal photography took place in and around New Orleans during the latter half of 2018 and into early 2019, with eight to 10 days of shooting per episode “depending on the scale,” Forrest notes. Originally produced for TNT, the series ultimately landed on Amazon Prime Video, where it’s now available to stream. Panavision caught up with Forrest shortly after the series premiered.

Panavision: How did you originally come to be involved in this show?

Trevor Forrest: I interviewed for it. Harriet Warner, the showrunner, had seen a film called Noble that I shot in Vietnam and Ireland and that had flashbacks and time shifts. She liked the period work, and that was partly the reason I got the interview. Another was through Sarah Aubrey, who’s now the head of [original programming] at HBO Max. We had just done [the TNT series] I Am the Night, and I had a great relationship with her and head of production Meredith Zamsky. They put in a friendly word for me, and they gave me the confidence to go in full bore. I thought, ‘If I don’t, I’ll regret it.’

When I went to interview, I knew they’d shot a pilot but were reimagining some of it. I was given a few words of their intentions, ‘epic and intimate,’ and that’s something I always try to play with. So I had this whole archive of images, things I had photographed myself or that I admired in other films, and I was able to put together a deck to illustrate my ideas. That’s where I pushed for the DXL. I really wanted to shoot with a large-format camera. I was excited by that as a photographer and DP. Large format wasn’t the norm at the time, so in my deck, I showed the difference between a 35mm photograph and a medium-format photograph. We ended up shooting DXL with the full sensor, but instead of 8K, we only recorded 2K ProRes 4:4:4:4, which was a mandate from TNT.

Shooting large format with the DXL was great because we could capture these amazing landscapes that feel epic — we shot T11 on the landscapes, with deep focus to convey the world of the swamps and the thundery skies — but then we could bring the camera down, put it on a shoulder and sit on a stool in front of Lily, and we had this whole landscape of her face to look at.

When the camera’s close to the characters, the shallow depth of field places them within what feels like an ocean of secrets — it gives visual form to the hidden truths that surround each of them. Even in a shot-reverse-shot, the foreground actor will be completely out of focus, suggesting that these characters are unknowable to one another.

Forrest: Going into this with the large format, I spoke with Harriet and director John Polson about how sound had to be similarly ‘out of focus.’ We wanted the ambience to close away and Lily’s breathing to come up so we could transition from the exterior world to this interior one. It needed that emotional layering with all of the storytelling tools to be successful.

What led you to pair the DXL with Primo 70 lenses?

Forrest: I’d heard about them a lot, and it’s the Primo brand, which I know well. It’s like an old friend — I know exactly how they’re going to behave. They’re such a strong workhorse. I can take Primos into battle and do anything with them. Even though I hadn’t used the 70s before, I’d used the Primo elements many times in different guises.

I knew we were going to be working fast — we used two cameras continuously — and I knew I wanted a lens that worked well at T8 as well as at T2. I knew those lenses could do that, and they’d match the Primo 11:1 [24-275mm zoom].

Were there any preferred focal lengths within your lens package?

Forrest: The 50mm was our main lens, and we would shift to a 35mm or a 100mm for moments that needed more action or to isolate Emma and go close to a detail — although we would use diopters on the 50mm before we would use the 100mm. The B camera would keep a similar setup, sometimes going to something longer if we needed them out of the way for a particular shot.

How did the DXL’s native 1600 ISO affect your approach to lighting the show?

Forrest: We used a lot of NDs in New Orleans! We actually used 800 ISO many times, but we definitely used 1600 often, especially for night scenes and to capture the tone of dusk. In some of our locations, we could barely get a light half a mile away down a muddy road, but we were still able to shoot in depth. So the 1600 was a game-changer. When we went out to the swamps, we even went to 2400, which was great.

How much time did you have to prepare before you started shooting?

Forrest: I had about four weeks. John Polson was on the ground already, which was great. I did a week at home, reading scripts and pitching ideas to him. Once I was in New Orleans, I was out photographing whenever I could, morning and night. John wanted to bring scale to the New Orleans landscapes. The moisture from the morning rain and the steam that would come off the road — we wanted to start fitting all these things into the story to build texture. My eyes were wide open daily.

Did you and John Conroy share any visual references as you were designing the look?

Forrest: I shared my reference deck, and he was definitely building on things he had done before, like Penny Dreadful and Broadchurch. This project was really about two cinematographers sharing something. It’s a design job in some respects; you want to curate something clear that you can pass onto somebody else. That’s something I learned from Matt Jensen [ASC]. He had done that for me with I Am the Night in terms of, ‘These are the film stocks, Cyan 60 on all the HMIs at nighttime, PVintage lenses, and slightly wider focal lengths for portraits.’ It’s just your top-line visual remit, and off you go. So I handed John that top line of DXL, epic landscapes, intimate portraits, and the beginnings of the flashbacks, which John took further because they more often landed in his episodes. It was nice the way it fell together with the even- and odd-numbered episodes having their own character. The duplicity of Karen and Emma was emulated in that handing off of the baton from one episode to the next.

John is such a good, gregarious, talented guy. We were both on the same page when it came to ratcheting up the suspense and tightening the grip of the thriller. We charted that in terms of more handheld, or more kinetic movement, or tighter lenses or closer wides, and intensifying on those levels [as the series progressed]. Within the thriller genre, we wanted something present and creeping, so we were in studio mode a lot of the time until the wheels come off in episodes 8 and 9, and then everything changed to handheld.

With the DXL being part of your plan from the beginning, you knew from the outset that you wanted to reteam with Panavision for this series. Beyond the camera, what brought you back?

Forrest: I’ve been so well treated by Panavision in my life, so I feel very comfortable there. Starting out, I was a clapper loader and an assistant to a lot of people, and Hugh Whittaker [at Panavision London] actually showed me how to load a magazine when I was about 21! I was also an artist before I was a cinematographer — I was a painter and sculptor and photographer — so I always find myself wanting to create something that gets you closer to the story, and Panavision really allow me to do that. Plus it’s one company around the globe, so if you want something from another part of the world, they’ll get it to you. It’s a really tightly run family.

Images courtesy of Amazon Studios. Words and interview courtesy of Panavision. Published with Panavision’s permission.