Artful Eyes

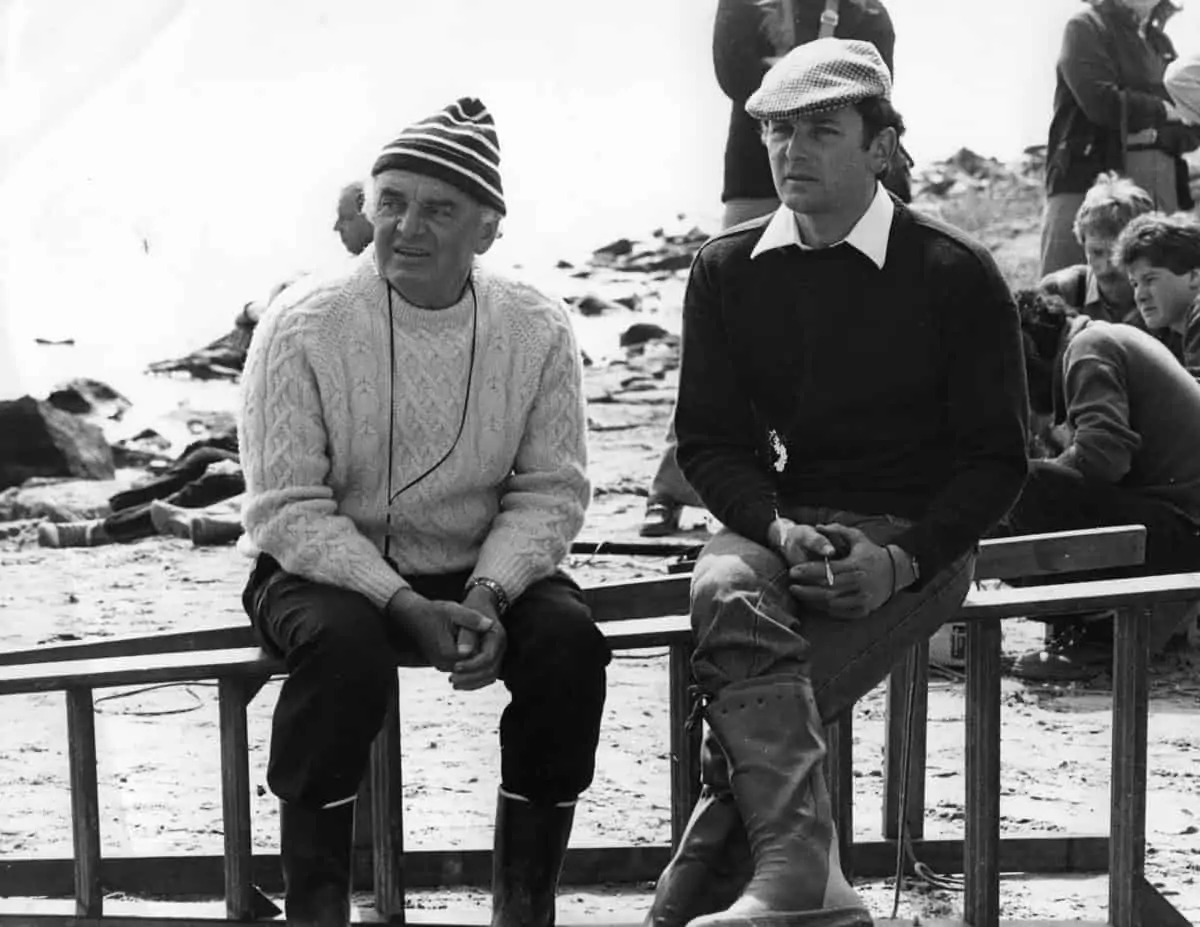

Clapperboard / Chris Challis

Artful Eyes

Clapperboard / Chris Challis

BY: David A. Ellis

Chris Challis was born in 1919 and was keen on films from an early age. He was educated privately at King’s College in Wimbledon, London. As a schoolboy he was very interested in stills photography, writes David A Ellis.

His father was a motorcar designer, who had an American friend who would come to England each year to watch and film motor racing on 16mm film. One year he gave Challis a 16mm camera and it was used to film events at his school. His father knew the managing director of Gaumont British (GB) News, a man by the name of Castleton-Knight, his first name unknown. Challis’s father mentioned to him that his son was interested in working with films and had shot some film. Challis was invited to meet and show his films to Mr Castleton-Knight. Challis went to Film House in Wardour Street, screened the films and got a job with GB.

He said: “It was around 1936, I was eighteen and I had just left school. For the first year I would get tea and rolls for the cameramen from the Sudbury Dairy café, which was next door to Film House. Occasionally, I was allowed to touch a camera.”

He spent around eighteen months with GB and then moved on to Technicolor, which were making its first film in England called Wings Of The Morning (1937). Challis said: “I got a job as a loader. My visions of being on the studio floor and mixing with the stars didn’t happen. I ended up working in the dark room loading the three black and white negatives.”

Challis worked for Technicolor until the outbreak of war. He then went into the RAF as a cameraman. After the war he went to work on A Matter Of Life And Death (1946) with Jack Cardiff. Cardiff suggested to Michael Powell, the director, that Challis could work on the second unit.

“I had to go up and see Mickey, as he was called, rather dauntingly, because I wasn’t really all that experienced. I got the job, and then the job of camera operator on the main unit, Geoff Unsworth was offered a film as a DP. I then took over as the operator on the main unit.”

The next film he operated on for Cardiff was Black Narcissus (1947). After that he went off as DP on End Of The River (1947). “After I had finished that film they were preparing to make Red Shoes (1948). I love ballet and wanted to work on the film. Jack Cardiff was the DP and I persuaded them to let me come back as operator on the film. I did Red Shoes and wouldn’t have missed it for the world,” said Challis.

After this, Powell, who had directed Red Shoes offered him The Small Back Room (1949). From then on he shot a number of pictures for Powell and Emric Pressburger. Pressburger was a writer and with Powell they ran a company called The Archers.

Describing Powell, Challis said: “Mickey was a hard taskmaster, he could be very unkind. He was out to judge people, I think pretty quickly. Once he had made a decision he never altered it. If he didn’t like you for one reason or another it was best to leave. On the other hand the people he liked and respected he was wonderful and was very loyal. He was one of those people that liked to be challenged. He liked people to stand up to him and most ran away.”

Asked what it was like working with Vistavision, Challis replied, “It was horrible, I hated it. My first contact with it was on The Battle Of The River Plate (1956). The cameras were awful and badly designed.”

When asked about his most difficult film, he said, “It was Saadia (1953), shot in Morocco and directed by Albert Lewin. I think it was the first Technicolor feature made entirely on location. All locations Al had picked were totally unsuitable. They were too small. One of the opening scenes was set in a small room housing eight or nine characters. With the blimp and a couple of lamps you couldn’t get in the room.”

Talking about 65mm, Challis said, “Shooting on 65mm wasn’t that much different to shooting on 35mm, except you needed more light. I worked on the 65mm Mitchell camera and was DP on two productions. First, Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines (1965) and then Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). It was fun on both films. Magnificent Men was difficult because of the process work. We didn’t have the sophisticated things they have now. We used a lot of travelling matte, which entailed a lot of problems, including depth of focus. Some of the problems were due to the wire rigging on those old planes, which disappeared in the making of the matte. So we had to increase the diameter of it all, making it much bigger so it worked on the blue backing. We then had depth of focus problems because most of the shots were on a pilot in the cockpit and behind him was the rudder and the tail plane. We couldn’t hold the depth of focus because the light level on the blue screen would only give us the maximum of T4. We needed a lot more, so all the sets had to be re-designed so they would be brought into the depth of field.”

Asked about his Rank days he said, “For a short period I was employed by Rank, which I absolutely hated. John Bryan an art director who became producer, whom I liked, did a picture called The Spanish Gardener (1956), which I photographed. John said, ‘Why don’t you sign a contract with Rank? You will only work with me and photograph my pictures.’ I did that, then John had a row with Rank and left. I was then left with this contract.”

"I got a job as a loader. My visions of being on the studio floor and mixing with the stars didn’t happen. I ended up working in the dark room loading the three black and white negatives."

- Chris Challis

Giving his thoughts on working for the great director Billy Wilder Challis commented, “I worked with Wilder on The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes (1970). Wilder was very tough with the actors, he didn’t allow any individual interpretation of the script. What was in it was what they had to say. He was a wonderful director, he shot long takes and he didn’t cover. He didn’t shoot anything he didn’t use.

“Another one like Wilder was Carol Reed. He was like a watchmaker, he knew exactly what he was going to use and how he was going to use it in the final cut. So you shot very little extra.”

Did he have a favourite director? “I liked working with Stanley Donen and Michael Powell. Not because they were the best directors. They were ardent filmmakers and fun to work with. They were very creative and they both had a very good visual sense, which made it very interesting from a cameraman’s point of view.”

Asked if he usually kept the same crew, he said: “As much as I possibly could. We were all freelance of course, so sometimes there were periods where you didn’t have work. If your operator had a chance of another film he had to take it so you did lose people. I was very lucky I managed to keep people for quite a long while. Freddie Frances was my operator for quite a while and then the late Austin Dempster, who was a wonderful operator.”

Challis’s last film was Steaming (1985).