Brendan Steacy ASC CSC uses ZEISS Supreme Primes on Painkiller

Aug 15, 2023

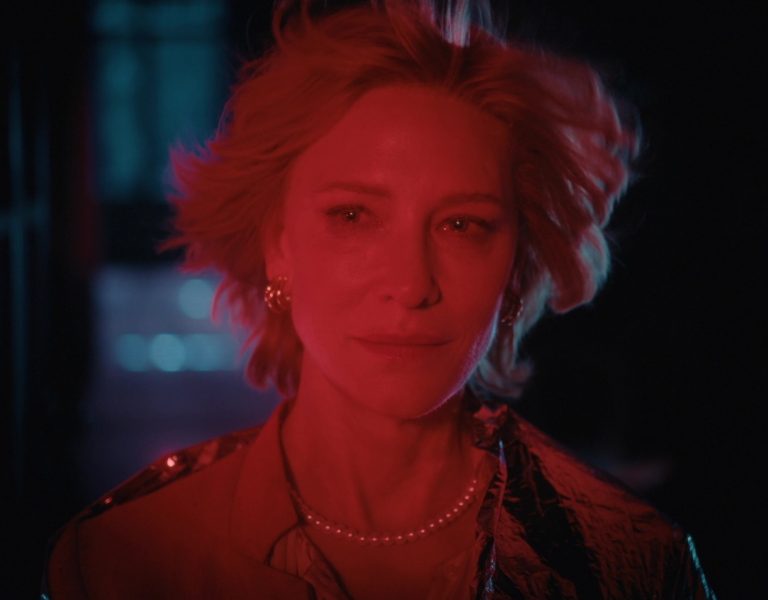

Newly initiated into the American Society of Cinematographers, Brendan Steacy ASC, CSC has been recognised for his beautiful cinematography that pushes the boundaries of style and storytelling, on features like Stockholm and Flashback, as well as series work on Alias Grace, Titans, and Clarice. Meticulous and scrupulous cinematic control has characterised his filmmaking, a status quo which was turned on its head with Painkiller, the just-released Peter Berg limited series, starring Uzo Adbua, Matthew Broderick and West Duchovny. To help embrace the often impromptu and performance-first series oeuvre, Steacy trusted ZEISS Supreme Primes with the ARRI LF to achieve his creative vision.

Painkiller explores the origins of the opioid epidemic and the devastating effects it renders across the nation. It interweaves the stories of an addict, an investigator, corporate pill-pushers, and that of the Sackler family. Steacy explains, “You take these individual stories that would otherwise be completely unrelated, and then you realise how one thing is connected to another. It’s told the way it is to bridge the intersection of these stories. Even peripherally, characters pass each other’s frames, and you see little nuggets–like someone who has not been introduced yet, visible in the background approaching a pill mill, who winds up becoming an addict later.

“Painkiller was a really unusual and interesting project for me,” says Steacy. Director Peter Berg is known for immersive, character-first works, and brings a one-of-a-kind philosophy to filmmaking. “I knew I was in for a crazy ride. Pete is vehemently opposed to any contrivance at all. He wants to feel like it’s discovered in the moment, all the time. In an instance like that, you have to let go of a lot of the control you’re used to.”

The production was unusually structured, with the intention to react to acting on the day rather than meticulously plot out every beat in advance. If a sequence that might have taken place over several scenes could be combined into a one, then often it would be, with the cameras taking their cues from blocking to catch cast moving between interiors and exteriors of a location. “By the time we blocked, we’d just roll it all as one long scene. We’d pull irises in and out of buildings and in and out of cars and it would be all connected. You roll two or three cameras, each with 25-minute cards then that would be the scene.” Finessing sets and lighting took a back seat to maintaining fluid performance.

Steacy needed a camera package that would let his team work nimbly and creatively in this anomalous environment. “The main consideration was to go small and light because the show is entirely handheld. We needed something that was fast because I really needed to be able to control where people were looking in frame.” That’s why he chose ZEISS Supreme Primes with the Arri Mini LF. “The lenses were one of the only tools we had left to us, and I needed to at least be able to control where someone’s eye goes and to make some of the background go out of focus.”

The lens set offered Steacy its own opportunity for him to let go of preconceptions and embrace what worked best in the moment. “I had tested the whole set and I thought I was going to use the 40mm the most, along with the 65mm. The 50mm is kind of the messiest and tests the worst, but I ended up shooting almost the whole show on it. I fell in love with it. It renders faces absolutely beautifully. It has the most aberrations, which actually gives it the most organic feel.” The dynamic, constantly fluid nature of Painkiller led him to treasure the lenses capable of both beautifully rendering a close-up then offering a wide frame of view when the camera shifted to a new set up mid-take.

Armed with this lightweight lens and camera body, the camera operators were able to accomplish long, intricate takes, that could last a full 25 minutes uninterrupted. Steacy recounts, “We had a big courtroom scene that was seven pages with all the leads and 200 extras. Camera operators, Iain Baird, and Bret Hurd, had incredible chemistry. They had this beautiful sort of ballet going on between them. They would talk to each other the whole time because sometimes they were walking backwards blind, both covering different people. Then they would intersect and suddenly they’d go into profiles and switch people, trying to time it on the fly.”

The long courtroom scene consisted of almost 60 setups between three cameras, which were accomplished in a single 25-minute rush of activity. “Suddenly one camera is going in for closeups and I literally had 1st AC Craig Jewell change the lens while we were rolling, in the middle of a take. If you watch the dailies, you can see the lens comes off and a new one goes on,” recounts Steacy. “The whole scene is handheld. You’re flying around and there’s no adding eye lights or tweaking. This is the room, we’re lit, now grab everything in both directions, including inserts, ultra closeups and giant wides. Everything’s all there in the same single take.”

From Painkiller, Steacy has cultivated a new form of filmmaking zen. “I wound up coming out of the show feeling like there’s a lot more to what we do than lighting, framing, and blocking–which is how I’d been forced to approach so many projects. I felt more like a collaborative storyteller than a technical facilitator.” Having a trustworthy camera package helped give the ASC cinematographer the breathing room to embrace the unfamiliar.