A researcher from Bournemouth University has solved a mystery that has baffled the film industry for over one hundred years by identifying the first motion picture ever copyrighted in the US.

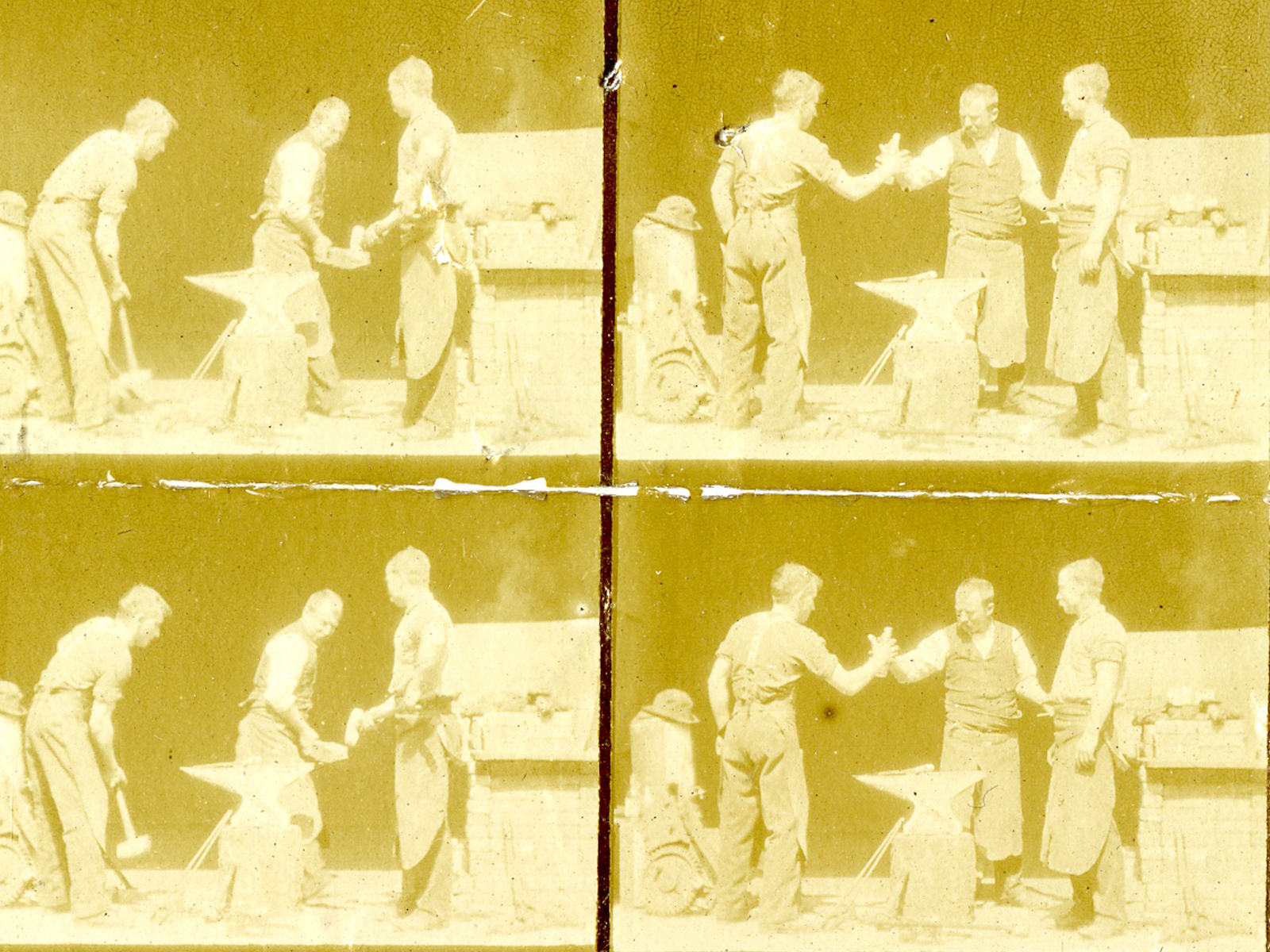

Dr Claudy Op den Kamp discovered that the film in question was “The Blacksmith Shop” made by W.K.L. Dickson, head photographer at Thomas Edison’s plant, in 1893.

The discovery by Dr Op den Kamp, Principal Academic in Film at Bournemouth University, also offers insights into how copyright law had to adapt to keep up with the pioneering filmmakers of the 19th century. Today, that process has evolved to register nearly 41,000 films a year – from independent producers up to the large movie studios.

Motion pictures were not covered by US copyright law until 1912, so early filmmakers made use of protection given to photographs by including copies of frames from their films alongside their copyright application letters.

Scholars have known for some time that a film registration had been made in late 1893 but the official copyright record book only describes it as “Edison Kinetoscopic Records.”

Despite decades of mining the archives, researchers have never found the related registration letter and accompanying frames, so no one has been able to tie it to an actual motion picture — until now.

Over the summer, Dr Op den Kamp undertook a six-month Kluge Fellowship at the Library of Congress in Washington DC – home to the US Copyright Office – to seek an elusive record that could answer one of cinema’s oldest questions.

The scale of her task was immediately apparent.

“This is the largest library in the world. It has one hundred and seventy-five million items, and its collection grows by twenty thousand items every day!” she said. “As soon as I got on site I realised how ludicrous the idea that I was about to go in there and look for this thing must have seemed.”

Of particular interest to her quest was the work of Librarian of Congress, Ainsworth Rand Spofford. As part of his many roles, Spofford would personally sign copyright registrations and was instrumental in developing US copyright policy at that time.

“Previously, people have been looking for the original copyright deposits – the application letter and the frames – and those are still missing,” explained Dr Op den Kamp.

“I decided to take a different approach in how I went about this and see if there was another piece of the puzzle I could find. I was convinced that Spofford must have had further conversations with the filmmaker because both the product and technology were completely new. There is no way it could have simply gone through the usual registration process without any hitches or discussions – he must have been involved at some point,” she continued.

She therefore set about her hunt for clues by looking at the story through a different lens – the work of Spofford who, despite his key role, is rarely mentioned in history books. This involved an extensive search of 250 boxes of correspondence to Spofford – each box relating to around 2,000 registrations.

“Unlike others who have tried to find the answer, I was fortunate to have this fellowship that gave me six months to focus on the task and explore every rabbit hole. The history of these documents is a complicated puzzle that involves, for instance, many relocations. Others would not have had the luxury of that much time,” she added.

With just one week left on her secondment at the Library, Dr Op den Kamp finally found the box where the secrets were hiding. She came across a letter sent from Dickson, dated November 1893.

Dickson was chasing Spofford for an update on a copyright application he had made a month earlier. The letter was accompanied by 18 images of Edison’s film “The Blacksmith Shop.” On the back of the prints, Dickson had written “sample sent last for copyright.”

Dr Op den Kamp’s conviction that further correspondence must exist that could reveal the secrets was correct as this letter proved that The Blacksmith Shop must be the film that the mysterious entry in the copyright record book relates to.

Recalling the moment when it dawned on her what she had uncovered, Dr Op den Kamp said, “It was nuts, it felt like I broke down physically! People came rushing over thinking I was hurt – I had to say ‘no, no, these are happy tears!’ It was magical that this happened whilst I was sitting in the Motion Pictures Department. The people that came running over understood immediately what I was holding in my hands, and it was wonderful to be able to share the moment with those restorers and archivists who live and breathe film.”

Previously, the earliest surviving film to be registered for copyright was “Fred Ott’s Sneeze”, also made by Edison and Dickson, in January 1894. This is now confirmed as the second film to be registered for copyright. Like other motion pictures in the early days of filmmaking, it would have gone through the same copyright application process that we now know was developed for “The Blacksmith Shop.”