BODY SHOCK

Benjamin Kračun BSC reveals the approach he adopted when shooting The Substance, working with prosthetics and practical effects to realise director Coralie Fargeat’s vision for the body horror.

The script for The Substance is 150 pages and 20 pages of that is dialogue. So when I read it, I thought it was amazing for a DP or for anyone visual. The content of the script, like the film, is not very subtle, so you get it straight away. I wrote down in my notepad, Showgirls meets The Fly meets Death Becomes Her.

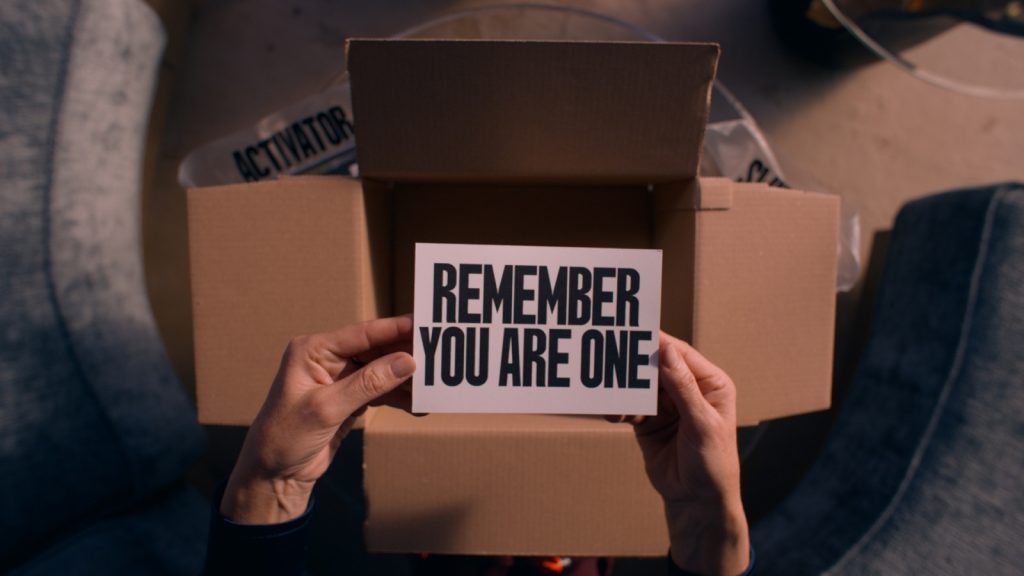

Reading [writer-director] Coralie Fargeat’s script was incredible because it’s all about beauty which is very timely as when you go out people are on their phones on Instagram, and there’s this obsession with image. In the film Demi Moore plays Elisabeth Sparkle, an aging Hollywood star who turns to an injection of luminous fluid called The Substance to generate a younger version of herself – Sue, played by Margaret Qualley.

Coralie talked about doing most of it practically, and we discussed the prosthetic aspect of the film, which made me even more keen to get involved. Most of The Substance was shot on stage and everything was real, with many sequences built using multiple different elements such as stage work, close-up studio, prosthetics, practical effects, and doubles. When I joined, before shooting began in 2022, Coralie had already extensively storyboarded all the effects and prosthetics sequences and had a very clear and distinct style.

The pivotal “birth” scene in a bathroom, where Sue emerges from a split in Elisabeth’s spine, is made up of multiple shots. We built two bathroom sets and part of the sequence plays out as if it’s one shot and then it goes into a POV from Sue’s perspective in the other bathroom where I was operating the camera shooting Sue so it looks like she’s looking at herself in the mirror.

There were days where Demi or Margaret would be in makeup for six to eight hours for the more prosthetic-heavy sequences so when they came on set you could only shoot parts of the scene. When filming all the details and close-ups we worked with doubles and shot two or three months later in what we call the lab – Epinay Studios in the north of Paris where myself, Coralie, two assistants, one art department, and one gaffer filmed for a month.

The best thing about working with prosthetics is it’s real. The tricky part is the time it takes for all involved, including the actors. Because it’s real, you have to find that balance of how much you’re going to see and not see. Prosthetics master Pierre Olivier Persin [special effects coordinator and supervisor] has a studio in Paris, so prior to filming, and especially later in the film when it gets more heavily into the prosthetics, we went into the studio on weekends or evenings to film tests, shooting the prosthetics on an iPhone or camera to work things out and be really specific about which parts to shoot because it would take so long to build.

The prosthetics in the birth sequence were shot in the lab in an almost table top set-up where we had the whole torso and part of the bathroom set. With prosthetics and live effects you’re always limited to the size of what you’re given, whether it’s a tabletop or part of the body, but you don’t want that to influence the way you shoot the scene.

Practical makes perfect

When Sue is born, the sequence begins on a top shot and Elisabeth is on the bathroom floor, writhing around. We’re then on the ground going along the bathroom floor which I captured using a Skaterscope to get really low. The shot moves into her eye and when the eye doubles that’s the only part of that sequence that’s VFX. The shots where the back splits open were filmed in the lab, where we relit the bathroom section. The special effects team could get behind it and press and push it as if a body was emerging. When the body breaks open – even though we only had that torso element – we tracked from left to right, and right to left again. When an arm comes out of the back that was actually someone’s real arm.

The shot then moves onto Sue’s eye as the pupil enlarges before entering a tunnel of light which was also shot completely practically. When shooting a tunnel of light on film there are more techniques you can use like reprinting, but we didn’t have that luxury shooting digital. However, because we were filming on a set in the North of Paris, most evenings after the shoot we would test all the technical aspects of the film as we went along. The tunnel of light ended up being super simple – two bicycle wheels on their side and Astera Titan tubes all the way around, which would spin together at the same speed and the camera was placed in the centre. A POV shot from Sue’s perspective follows and she stitches up the back – with the wider material shot in the bathroom set, and close-up stitching shot in the lab.

At the beginning of that sequence Elisabeth looks at herself in the mirror and injects herself. The injection in that shot was actually into Coralie’s arm and filmed in the lab because she wanted it to be a real injection. For this sequence I wanted to recreate the look of an effect I really like when shooting on film where you drag the film through and process it back at a different frame rate which produces a blurred motion. But you can’t do that digitally, so we filmed it at five frames to create an optical flow effect when the DIT transcoded it. So instead of it playing back at fast speed, it played back as if those five frames were dragged over 24 frames, creating a blurry motion.

The grade was carried out at Lux in Paris with grader Fabien Pascal and they also helped build a very strong LUT which was great but quite heavy and took away at least a stop and a half of light. As well as working with them on a LUT for the prosthetics, another important part of the film was the liquid for The Substance which needed to be fluorescent. The props department created something that looked fantastic but was only fluorescent when you hit it with UV light, so Lux also made a LUT for any time the fluorescent liquid was shot.

Another significant setting in the film where many scenes took place was the apartment which featured a huge panoramic window. Coralie wanted the glass to have nothing in front of it and the big question was whether to choose LED screen or backdrop. I quickly realised the LED technology was so new, expensive, and tricky to use with hard light because if anything bounces back it would make it look grey. So I tested shooting against softdrop which had a kind of romanticism and I thought was more interesting than the LED system.

That also directly influenced the camera package when I tested different cameras and lenses at RVZ in Paris. I wanted to shoot anamorphic at first, but when Coralie started talking me through the sequences she’d already storyboarded, which were the effects sequences, there was so much close-up work I knew it needed to be spherical. I like older glass and ended up with the Canon K35s on an ARRI Alexa Mini LF because the skin looked so good on the ARRI sensor when we projected it. The film has such a microscopic view of skin and beauty, I needed to keep it as clean and natural as possible. I chose the K35s because of the drop off – not even shot wide open, but at 2.8 or 4 – and because they’re vintage lenses it really helped when shooting against that softdrop.

Inventive illumination

Coralie often wanted to go right into the prosthetic and it had to look really good so I used a Leitz Thalia 24mm – a wide lens that can focus almost to the glass – Cooke 90mm Macro, and ARRI Macro 200mm and diopters. Sometimes I would light to hide some of the prosthetic, but Coralie wanted to see way more and all the wrinkles.

I found it trickier lighting the bathroom setting where the birth sequence begins. Coralie wanted the bathroom to be super bright, clinically bright. So sometimes we were adding in a little bit more because we wanted to show all the veins and all the colour. But I found it most effective when we treated it as if it was real or hid some of the prosthetics from the audience.

The bathroom was a mixture of tungsten – for the quality – and LED because of the speed we were going from night to day. Coralie initially wanted the bathroom to be completely tiled but because there were so many sequences in there and we’d have to light from the front, we couldn’t move a big bank of frontal light every time. So we built six ARRI SkyPanel S-360 lights into that set and one mirror light which was a smaller Astera tube with a cover on it. When working with gaffer Guillaum Lemerie, because the shots are essentially beauty, every time we moved in closer it was all about how we could soften and shape the light as much as possible.

But in the living room of the apartment Coralie wanted to create hard LA sunlight during the day which was another reason we went with the backdrop. There we used four 24K ARRI fresnels on movers so we could move them and change the light. We had around 50 SkyPanels and for the night work we mixed Orbiters and Astera tubes to pick out little streets.

Coralie likes to move the camera 360, especially around a character, and I was lucky to have a great Trinity operator, Benjamin Groussain, to achieve that. When you move the camera in that way there are not many places you can put lights, so we had to come up with inventive ways to light scenes such as one of the sparks moving in with a light.

Coralie was also very specific about wanting to shoot every shot and for most of the film to be single camera. It’s the kind of film that, if you were shooting in America, you would get half or a third of the days we had and I would get three units which I would run. While a 100-day shoot might seem like a lot – and it was my longest film shoot – when you take into account the prosthetics, that Coralie wanted to largely shoot single camera and for us to capture every shot, with three weeks of that in a lab and another three on location in Nice and Cannes doubling for LA, it was really like three or four different shoots.