MASTERPIECE OF MYSTERY

When lensing Mare of Easttown, Ben Richardson ASC embraced the opportunity to play a part in telling a human story within a classic mystery framework. The cinematographer discusses incorporating scale in small, domestic spaces, embracing simplicity, and capturing moments of accidental beauty.

Mare of Easttown – the HBO limited series starring Kate Winslet as Mare Sheehan, a detective investigating a murder in a small, bleak town in Philadelphia – has gripped, moved, and charmed audiences in equal measures. It’s also received critical acclaim and 16 Emmy nominations, including an Outstanding Cinematography for a Limited or Anthology Series or Movie nomination for the episode Illusions. The appeal of the unglamourous yet compelling portrayal of small-town rural America and authentic, complex, and damaged characters was clear from creator and writer Brad Inglesby’s script.

Login to continue reading

This content is exclusively for digital magazine subscribers.

Start your subscription today, or login below to continue.

When British cinematographer Ben Richardson ASC (Beasts of the Southern Wild, Yellowstone) read the first few episodes’ scripts before interviewing to shoot the series, he was instantly enthralled. He also had one request for the producers: “Whether you hire me or not, please promise you’ll let me read the remaining episodes’ scripts. I can’t wait a year to find out what happens.”

Above all else, Richardson – who is “always on the lookout for human dramas” – was desperate to find out how the captivating story evolved. “What I find most compelling about filmmaking is its direct connection to the great history of people trying to understand what it is to be alive and the losses and difficulties we encounter along the way,” he says. “The scripts were a perfect combination of the classic murder mystery framework and a wonderful human story, particularly in the form of Mare and her personal journey. Ultimately, that was the real story of the show, above and beyond the mystery she was trying to solve.”

As well as feeling elated to tell Inglesby’s story alongside director Craig Zobel and a skillful crew, Richardson was intimidated by the task of incorporating scale and scope into a project with many characters where the action played out predominantly in small, domestic spaces. “Having worked on productions set against a more expansive natural backdrop over the last few years I was a little nervous as so many of Mare of Easttown’s heightened emotional human moments take place in living rooms, bedrooms and small-town exteriors,” he says.

Richardson discovered if he embraced the naturalism and simplicity of the characters’ lives, he could “find richness within the details of the spaces.” “Close allies” such as production designer Keith Cunningham helped bring the spaces to life, giving the audience a sense of the characters’ personalities and environments. Within that framework, Richardson found ways to create scope.

Director Zobel aimed to “find balance and the threads that mattered in the totality of the huge story”. Many of his conversations with Richardson focused on where to place emphasis. “The seven hour-long episodes feature a huge number of characters and locations, so it was very much about finding the right places to be restrained, or to give emphasis to a point, or help the audience go with a certain character,” explains Richardson.

The filmmakers were mindful not to exaggerate moments or provide too many overt red herrings. “It’s a murder mystery so there are beats where the audience find themselves slightly misdirected,” says Richardson. “But we were conscious to never make those moments artificial or to use a creepy low-angle push in on someone’s face at the end of an episode only to reveal in the next episode that they were a nice character. The audience would feel cheated.”

Instead, focus was placed on how to keep spaces alive using the camera and lighting design, giving themselves free rein when exploring styles of camera movement and balance of shot sizes. “We discussed what constituted a close-up and what do we save extreme close-ups for, which we use a handful of times in the series,” says Richardson. “What does a close-up mean for an audience? And how heightened did we want to make a moment beyond what the performers were already giving us?”

In support of the performance

Phenomenal casting was a lynchpin in the series’ success. “As soon as I saw the wall of faces during pre-production I just thought, ‘Oh my god, we’ve got this show.’ From Kate Winslet all the way through the superb line-up, there was a wonderful combination of compelling but real-looking people,” says Richardson. I realised that was the anchor for how we would shoot the series. I could treat it like a type of portraiture, allowing the camera to embrace and explore the nuances of the different faces and personalities.”

The entire crew acknowledged that everything needed to be in support of the performances. “The camerawork just became another part of that puzzle,” says Richardson. “It was about what would invisibly heighten the audience’s experience of these performances. What movement – that they’re not even aware is happening – adds something extra to what is already a wonderful moment?”

From the initial meeting with Winslet, Richardson recognised the way she read the character of Mare was completely aligned with what Ingelsby and Zobel had intended. “This series was one of the most satisfying production experiences I’ve had because I believe we were all on the same page,” says Richardson. “The design of each day and every scene became more fluid and fun because we rarely disagreed.”

Lens tests determined that the 40mm was perfect for most of the close-ups of characters. “Close-ups in many of my recent projects have been on 135mm or sometimes 180mm lenses – which I love – but that just didn’t feel right in the spaces we were shooting,” he adds. “If we shot close-ups of people on long lenses, all the environmental information about them disappeared. And we found moving a little closer, and not necessarily changing lens, brought us into a very intense emotional space with the characters. But we had to be careful about when to use this.”

One sequence that justified this approach – one of Richardson’s favourite shots – was a slightly high-angle close-up of Mare in her therapist’s office as she revisits the memory of her son’s suicide. Shot choice was “born from the performance”. “I watched Craig working with Kate in rehearsals and saw her enter this reverie moment. She looked up and away and drifted into this meditative state as she let the words out,” he says. “I felt that if we placed a camera above to catch her in that moment, we could invite the audience into her experience in a way nothing else in the series could. The shot is on screen for 45 seconds – it’s one of the most compelling, beautiful moments with Kate. It was just about where the camera needed to be to best support this special performance.”

Freedom to explore the environment

Shooting Mare of Easttown only 30 miles south of Philadelphia and near the places detailed in Inglesby’s script enhanced the production’s authenticity. When shooting on location, this gave Richardson freedom to point the camera anywhere. “You often find yourself hemmed in, with only a small window that really works with the show’s aesthetic, but the locations were exactly how Brad had written them,” says Richardson.

The locations’ accuracy allowed the crew to achieve the stillness they set out to convey in the first few opening episodes. As the narrative evolved, the aim was to demonstrate that Mare is the one character willing to break that stillness, make a change and seek the truth.

Aesthetically, Richardson enjoyed the quality of light experienced when shooting in Pennsylvania. “It is similar to the UK’s natural and unique quality of light which I adore – low heavy cloud with a softness and depth to the shadows.”

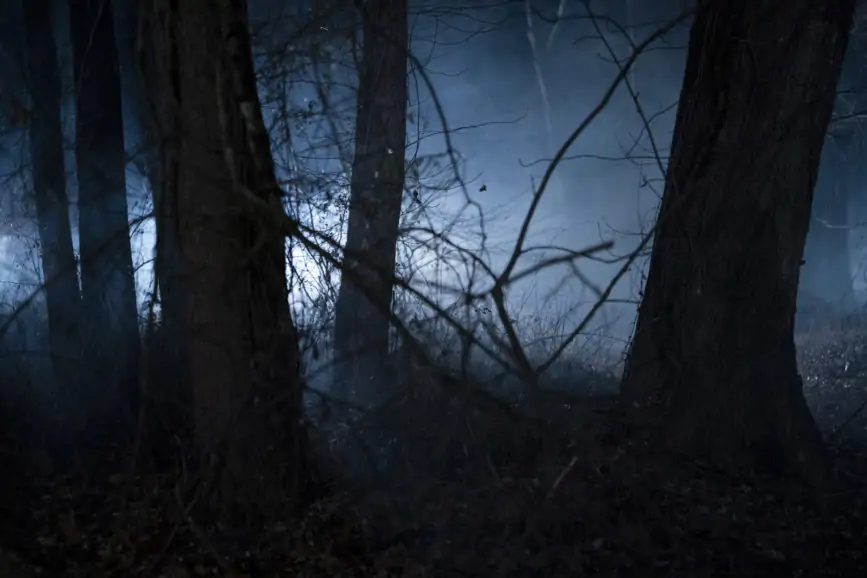

The series comprised an equal amount of location work and set builds – Mare’s house and the police station being the two largest stage builds. Difficult locations encountered included the large underpass where the first episode’s night-time party in the woods takes place. “Lighting the large area and moving equipment was difficult, but I love how that scene looked. It reminded me of my teenage years and had the vibe of being freezing cold, but still everyone is just hanging out and having fun.”

Shooting a sequence in Coatesville which sees teenager Jess being chased was especially tough. Although it was one of Richardson’s favourite visual locations, those nights were some of the coldest times he has worked. “Equipment stopped working, dollies wouldn’t boom, the lift hydraulics froze up. Shooting Wind River in Utah was pretty damn cold, but it strangely didn’t compare to this. We recreated the moment where Jess hides under the car on stage because we couldn’t ask her to crawl around in those conditions.”

Moments of accidental beauty

Drawn to source-driven naturalism, Richardson endeavored to justify where the light was coming from in every scene. When telling character-focused, authentic stories such as the one that unfolds in Mare of Easttown, he wants the audience to feel like they are in a grounded environment. “You don’t want viewers to sense there are additional lights because that kind of artifice allows an audience to take it for an unreal story. I want them to feel like everything we’re capturing is real and happening in real time.”

This was realised through broad, soft light sources, and judicious use of hard light where appropriate, “bringing the sun in occasionally”, often to make a scene look hard and cold. “The Philadelphia winter sun is so low on the horizon. It stabs in through the windows at very low angles and is not exactly comforting,” says Richardson. “Its hardness makes you aware of how cold it is outside, and we really played that low hard, sun in the series. For the more lighthearted scenes, we could also play it as a warm sun, bringing the sun angle up another 20 degrees so it felt safer and more inviting.”

The tungsten-heavy production relied on many open-faced 10K and 20K sources to recreate the sun. Richardson also discovered the Lupo Superpanel – a bi-colour, fully dimmable, battery-powerable 1×1 LED panel which was valuable for interiors and often used as the primary bounce source. “Their diodes have a beautiful spectral output and do wonderful things to skin tones, with many of the same qualities as tungsten while being simple to use and lightweight.”

For some sunlit scenes, particularly in Mare’s therapist’s office which is supposed to be on a high floor in the building, Richardson and gaffer Nina Kuhn used Cine Reflect Lighting System (CRLS) aluminium bounce reflectors. “The finely polished aluminium, mirror-like surfaces are not just hard mirrors. They have grades in the middle that create beautiful, softened light which is also very specular,” he explains. “Plus, when you bounce a source into them, you extend the distance and so have less fall off. Instead of the lamp being outside the window, the reflector is, and the lamp is another 12 feet away. The quality of light feels more like natural sunlight than anything I’ve used.”

Although Mare of Easttown marked the first time that gaffer Kuhn collaborated with Richardson, she quickly understood and embraced the lighting aesthetic he searched for and adapted in location and stage environments to maintain it. “She always pulled out my favourite units and was terrific at texturing the deeper backgrounds in our exteriors. Nina has a real artist’s eye,” he says.

As with many of his previous productions, Richardson experimented with broad, soft, low intensity sources and their ability to model a face, the aim being for the audience to never feel like characters were intentionally being made to look beautiful or frightening. “Once you learn a handful of techniques to make somebody look just beautiful and glamorous, it’s almost harder to find ways to make them look beautiful and natural, which was important here,” he says. “I wanted it to be a coherent visual experience – that this was how the world looked and we just happened to be there to capture it.”

The cinematographer revels in embracing the “complexity of natural light” as he looks for that “moment of almost accidental beauty”. “I want spaces to feel as rich and as textured as the magical moments we experience as we go through our everyday lives,” he says.

Production designer Cunningham’s influence in realising a plausible on-screen reality was also undeniable. He and Richardson dedicated many hours to exploring wallpaper, paint textures, and the types of practical lamps that could feature in the spaces. “We looked at locations that would help us play out certain scenes just using practical lights, some that would be good motivators for a more cinematic style of lighting, through to environments where there’s a requirement for the location to provide exactly what the audience sees on screen.”

Pandemic practices

When production was forced to shut down in mid-March 2020, a little over half of the series had been shot and as scenes were filmed out of sequence, no complete episodes had been captured. “Unlike most episodic TV – which tends to return to locations periodically throughout the season – we needed to visit many places and incorporate a lot of characters. There were scheduling issues due to actor and location availability, so we cross boarded, and block shot all seven episodes, filming at each location once and shooting out of sequence.”

Tracking emotional beats throughout this process demanded incredible skill and determination from the cast and crew throughout the 119-day shoot. “There are scenes in episode seven, for example, where footage from day eight is cut with footage from day 118. While tracking that was difficult, it also gave us a framework so we could evaluate what we had done previously and look at how we could play off certain things,” says Richardson. “With one director and one DP, prep was always a bit of a rolling process, but when we returned after the forced break, we had an opportunity to evaluate what we had accomplished and explore what to emphasise. We were like a well-rehearsed band and could riff off previous ideas explore new ideas within a framework we already knew was working.”

When the production returned to Philadelphia in August, everything was rescheduled based on a desire to shoot as much as possible on stage for safety reasons. During this period, the Girard College campus provided many controllable exteriors. As the crew was justifiably concerned about COVID and the consequences of an infection spreading throughout the production, team members were always masked and socially distanced.

Richardson began using Riedel’s Bolero radio communications system to talk to the camera operators, electric department, director Zobel and 1st AD Kayse Goodell. “We couldn’t talk face-to-face. I spent most of my time sitting 10 feet away from Craig. We had to learn how to collaborate without being able to just turn to one other to discuss a take,” says Richardson.

Communication for the second half of the shoot was over radio, which worked well under the circumstances, but is not something Richardson would normally encourage because “it’s a strange and isolating way to work”. For him, one of the most enjoyable aspects of being on a film set is “the camaraderie between the group”. “The Bolero was incredibly flexible though. I’m using it on the show I’m currently shooting too,” he says. “At the push of a button, I can speak individually to camera operators, my gaffer, director, and AD.”

Recently, the use of atmosphere has been widely discussed in the film and TV industry due to safety concerns that droplets added to the air could behave as a carrier of coronavirus. The initial feeling was that atmosphere would not be allowed on the Mare of Eastown set. “I don’t use it much, but I think having a touch of atmosphere in a space helps a camera see the world more like we do,” says Richardson. “Cameras have a tendency to show the world a little too clinically and I believe having a sense of depth is important.”

Atmosphere was explored by the ASC’s Future Practices Committee – created in May 2020 in response to the challenges the pandemic presented. Their investigation revealed one type of atmosphere commonly used on film and TV sets – Triethylene glycol (TEG) – is a common ingredient in air sanitizer products, regulated by the EPA. “Luckily, this product had been one of our primary atmosphere choices, so we receive approval from the studio to continue using it,” says Richardson.

The cinematographer has used remote heads for some time, finding working with a simple remote head on a small jib offers a fluid, straightforward way to achieve dynamic camera moves with the A-camera. For the first half of Mare of Easttown, the B-camera was typically on a traditional fluid or geared remote head, operated from the dolly. “After the pandemic hiatus, we switched to using two remote heads because the camera operator and dolly grip are normally physically close, and we had to avoid that whenever possible,” says Richardson. “By putting a remote head on the cameras that are on the dolly, only the dolly grip needed to be there while the camera operator could be further away from set.”

Revealing information

The Alexa Mini’s “bulletproof image” made it an obvious choice for capturing the series. “It offers everything I need from a motion picture camera, and I love the range of lenses it’s compatible with,” says Richardson. “It’s robust, no matter what the environment or colour temperature is or whether you are working with mixed lighting. The under-exposure capabilities are impressive too, although I don’t like to live on the bleeding edge of exposure. I’d rather give the camera a healthier amount of light.”

After embarking on a lens deep dive to assess numerous models, the Leitz Summilux-C came out on top, supplied, along with the cameras, by ARRI Rental in New Jersey. “The lenses are beautifully sharp where they need to be, the fall off is gorgeous, but the backgrounds are a little imperfect,” says Richardson. “They have some life to them, they don’t just disappear into a haze of defocused mush, like many modern lenses do.”

Zobel and Richardson primarily keyed camera movement off performances. “I never wanted it to feel like the camera was trying to spoon feed the audience or tell them how to see a scene,” says Richardson. “You can give an audience a tremendous amount through subtle camera movements. Keeping a moment at a distance or bringing them into character’s intimate space and thoughts.”

Handheld is used sparingly, one of two occasions being during a flashback sequence that is a pivotal plot point surrounding Mare recalling her son’s suicide. “It felt like going handheld for that moment was absolutely the right move,” says Richardson. “There was an intensity to that scene which was a composite of three elements shot in three different locations. We did things in that sequence we didn’t do anywhere else because it was such an important part of the story – when Mare confronts something significant from her past with her therapist for the first time.”

Other action-packed sequences peppered throughout the series which unearth vital details required in-depth conversations about the beats and amount of information to reveal. “We didn’t want the audience to feel like we were withholding anything in a way that would be frustrating, but we also didn’t want to give too much away,” says Richardson. “You want to let the audience have these moments. It became focused on the specifics of the composition and whether we should frame or obscure something.”

A gripping and significant scene which sees Mare being chased and hiding in an attic called for meticulous storyboarding. Richardson, Zobel and ADs Kayse Goodell and Blair Howley spent a day in the location exploring the best angles for every shot. “Due to the pace at which things would unfold and how it would be edited, we knew we had to give the audience the important moment through careful shot composition. When you’re dealing with that kind of action, you don’t want to rely solely on quick cuts to provide the energy – every shot must be designed to fulfil a role,” says Richardson.

“We also didn’t want it to suddenly feel like a different show and to be running around with a handheld camera like Jason Bourne. But we wanted that energy and Mare’s desperation, so we worked closely with Keith on the design of those spaces, finding things we could shoot through and around without changing the style of the show.”

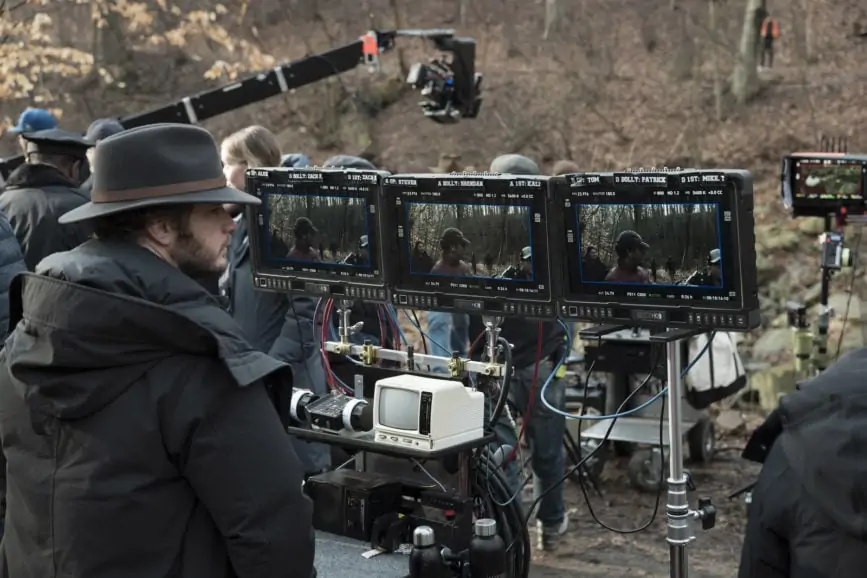

Richardson worked with “terrifically talented operators and incredible allies” – A camera operator and 2nd unit DP Steven Finestone, B camera operator and Steadicam operator for the pre-pandemic block Kyle Wullschleger, and for the post-hiatus block Alex Kornreich – to capture every beat. “It’s so reassuring to have a reliable and skilled team because when shooting multiple camera shows, I don’t tend to operate the camera anymore. I do miss it, but once you have more than one camera in play, I like to be able to keep eyes on them and know what I’m crafting is exactly what my first and second camera is capturing.”

It was also a “delight to collaborate with absolute legend of a grip” Mitch Lilian and his talented team. “When you find a grip team that really understand that efficiency is a key part of filmmaking, it is incredible,” says Richardson. “I could ask Mitch to put a camera anywhere and move it in any direction, and it would just happen without me having to worry about the mechanics.”

Looking for the lightness

While Mare of Easttown tackles hard-hitting subjects and is far from glamourous in its portrayal of characters, director Zobel still “searched for the lightness”. “Aware you can’t grind people down for hours at a time, he looked for moments that could ease the tension such as the light-hearted scene when Mare calls a family meeting,” says Richardson. “We looked at the way the scene blocked out and decided capturing it in a oner was best. We could afford this moment of the camera being a weird observer of the dynamics between the fractured and fragmented family whilst actively connecting them.”

Similarly, it was important the show did not feel heavy and grey throughout. “Craig was adamant it couldn’t just be an overall desaturation or feel muddy and muted,” says Richardson, who shared the director’s goal. “Going back to my first movie, Beasts of the Southern Wild, I’ve always loved building towards a look with a natural baseline of saturation. This lets you pop colour out much more effectively when those moments of colour do come.”

To achieve this in the grade, Richardson worked with Company 3’s Mitch Paulson, who he has collaborated with for the past five years. “His overall aesthetic taste is the same as mine – everything must be grounded in a natural look. It should feel realistic and plausible, but within that framework you have a lot of flexibility,” says Richardson. “This series was mostly about moderating the overall colour temperature. The winter sun in Philadelphia isn’t soft. It’s a little sharp and dazzling, more on the pink side than yellow. Knowing we had those things to play with and that we could keep this coolness and hard-edged quality of light, meant when we decided to pop it out and warm things up, the audience felt real relief.”

The process of creating the series emphasised that simplicity is key. As the crew moved deeper into production, the lighting, or the way the camera moved became simpler, and yet the results on screen felt richer, more textured, and more in tune with the scene or performance. “It was interesting to do something so small, domestic and urban and to leave it feeling we’d done justice to that world and made it feel as complex and meaningful to an audience as it did to the characters,” says Richardson. “It felt like it was hitting all the beats and had all the intended emotional strength and resonance. Our ambitions for the cinematography were there on screen. It was simple, mostly invisible, and supported the performances and the world being created.”