With no end in sight to the strikes, the Emmys are shifting from their usual September slot to what it hopes are less turbulent times. Nominees Natalie Kingston and Jon Joffin ASC give us the lowdown on their shortlisted projects.

“It’s quite surreal,” says Emmy nominee Natalie Kingston, whose work on the Apple TV+ series Black Bird scored her a first-ever nod in the Outstanding Cinematography for a Limited or Anthology Series or Movie category, for the “Hand to Mouth” episode.

Her comment about the surreality of it all came in answer to our question not just about how it felt to get nominated in general, especially for a first time, but also how it felt to get nominated now, in the midst of a strike. The emailed query – Kingston was on location, so kindly wrote back when she wasn’t busy shooting – came just ahead of SAG-AFTRA joining the writers, and bringing most of what was left of working Hollywood, to say nothing of the current award season, to a standstill.

Even more so since swapping those missives, as the Emmy awards have now officially been delayed to a “TBD” slot sometime in the future – perhaps October, as some hopeful prognosticators have suggested, but likelier sometime January-ish, early in the new year, around what is usually known as “Academy season” on the showbiz calendar, replete with its BAFTAs, guild awards, Golden Globes, et al.

This, of course, includes the Creative Arts Emmys, the one we mostly cover here – which is the weekend (since it takes two evenings!) prior to the main telecast, where all the crafts folk, from songwriters to production designers to VFX supervisors, costumers, editors, numerous categories of guest stars and animated shows, and of course cinematographers, all get their awards.

This column then, coming toward summer’s end (putting aside the question of whether hot summer weather really “ends” anymore in our literal “superheated climate” as opposed to the metaphorical one settling over Hollywood and its labour troubles), would normally be our last one before that ceremony. Next month’s would be a report on the award evenings themselves.

Twice as nice

By way of unexpected silver linings, then, we’ll have more time to hear from other nominees in subsequent columns. This month, in addition to Kingston, we also talked to Jon Joffin ASC, making him perhaps the first cinematographer we’ve interviewed for separate series in back-to-back columns.

Last time, you may recall, we spoke of his sterling work on the early 25th-century-set episodes of Star Trek: Picard, which aired – to use that quaint old term for “streamed” – around the same time as the second season of Schmigadoon! arrived (on that same Apple TV+ platform showing Black Bird) for which he now has his second-ever Emmy nomination, this in the half-hour series category for the “Something Real” episode.

When we spoke with him, he was busy taking a hike in British Columbia, where he lives, and noted – with the usual cinematographers’ eye – that he was “passing a huge rock structure that was super mossy” as we were talking. As with Kingston, the Emmys hadn’t even been officially delayed yet, but Joffin was already feeling the effects of the twin-strike, waiting to hear if another project he’d been tapped for would still proceed in the fall, and wondering if he’d have to go back to shooting “weddings and Bar Mitzvahs” to make ends meet, if it didn’t.

He tried to take things in stride (perhaps literally, given the hike) and said he’d hoped the producers would do the right thing and show the world that they are not “robber barons”, to use that fine old – and newly re-applicable – Gilded Age term.

Though even pre-Gilded Age terms are gaining currency again. SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher referenced Versailles in her initial press conference on the first morning of the actors’ strike, alluding to events wherein marchers forced the royals out of their palace and down the road to Paris, and helped ignite the French Revolution.

And yet, despite the fiery rhetoric, which has continued, Hollywood’s own economic royalists (to borrow a phrase, in this instance, from Franklin D. Roosevelt) appear to remain unruffled and in no particular hurry to settle things.

Though, as the handicapping goes, the studios will eventually need actors to promote all those fall and Oscar-season releases, won’t they? Well, in theory yes. An additional scenario holds that if the AMPTP did go ahead and settle with the actors first, then perhaps the Emmys could go on before year’s end.

Except there’d be no-one to write the patter for all those actor hosts, who would be left to ad-lib, and still be keen to talk about the plight of the unsettled writers’ strike on national TV.

Meanwhile, even in times such as these, nominees like Kingston remain gratified to have their work – and that of their crews – honoured by their own peers in the television academy.

“I’m very proud of the work we created,” she said. “I share this nomination with my incredible crew, and without them none of this would be possible.” Indeed, Kingston’s nod is the only one on the crafts side for the prison drama. Lead actor Taron Egerton is nominated for his role as the undercover-yet-incarcerated lead, as well as Paul Walter Hauser and the late Ray Liotta, in the supporting actor categories.

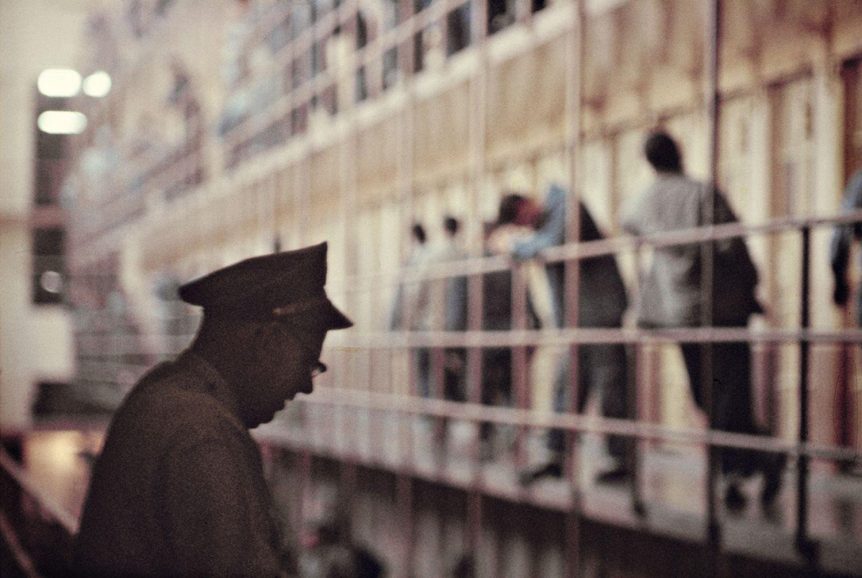

But how one divides one craft from another in terms of what or who to nominate can remain a mystery. Kingston, though, is quick to thank her collaborators: “We had a fantastic creative team amongst the other departments who brilliantly contributed to the visuals. Production designer Charisse Cardenas, costume designer Amy Roth, and I worked very closely to achieve the pastel colour palette in the prison that was inspired by Gordon Parks’ photo series, The Atmosphere of Crime. Charisse found the perfect shades of light pink, pale yellow and sea green for the prison walls. Amy’s patinated blue prison uniforms exquisitely contrasted the production design. The work of makeup department head Nana Fischer and hair department head Kathrine Gordon is incredible as well.”

Interdepartmental effort

Joffin, in contrast, was nominated along with the show’s production designer Jamie Walker McCall and his team, and choreographer Christopher Gattelli. Which makes sense, for a show in which its leads, Keegan-Michael Key and Cicely Strong, keep falling into alternative universes based on Broadway musicals, which not only overlap with and inform each other, but ultimately help the couple reckon with some pressing life lesson. In season two, the musicals drew from edgier ‘60s-‘70s-era fare, like Pippin, Cabaret, Godspell, Jesus Christ Superstar, Sweeney Todd, Sweet Charity, Chicago, and others (“there’s a huge Bob Fosse influence,” Joffin notes, and also some Umbrellas of Cherbourg, to boot) – all lovingly sent up.

But each of these provided a kind of “known look” for the shows being riffed from, sometimes verging on the iconic, such as the flapper bob worn by Dove Cameron, who plays a Liza Minnelli-esque Sally Bowles character during this season. The series itself had established a kind of look as well, in its more Rodgers-and-Hammerstein-era first season, so much so that Joffin says “when I got the call about this show, I wasn’t sure I wanted to do it. The first season had such a specific look. I was hesitant to be a part of it [but] when I met them, they blew me away with what they wanted to do.”

Part of that included trusting folks like series co-creator and writer Cinco Paul (an Emmy winner last year for his songwriting on the show, and also a producer/writer of the Despicable Me films).

He recalls one scene set in the very Kit Kat Club-like nightclub around which so much of the season’s storyline swirls. In it, Strong and Key have brought Alan Cummings and Kristin Chenoweth’s orphan-imperilling, Sweeney-ish characters there for a night out, and hoped for epiphany, as they seek to bestow “happy endings” on those around them.

Joffin had been thinking of various camera moves for the sequence, taking in Cummings and Chenoweth in the foreground, and the leads in the rear, but “Cinco said he’d like to do it all in one shot.” Joffin thought perhaps he was just trying to move through script pages quickly, but Paul reiterated that he “just wanted a static wide shot. If it doesn’t work, we’ll do something else.”

And so, with the two “layers” of characters moving within frame – a visual motif straight out of theatre – you see “how the people are reacting in the background. You see Keegan and Cecily masterfully reacting in the background. And the performance was so good, it played in one shot. Every note he gave,” Joffin adds, “made everything so much better.”

“Even in colour timing,” he adds. Paul “kept sucking the colour saturation out of the picture” for the “drab” beginning, which later “gives our Technicolor look a huge impact”.

Though he also credits Company 3 senior colourist Jill Bogdanowicz who helped build a LUT for the show where, she said, “colours stayed in their lane,” which was good, as the Technicolor palette blooms in the later episodes as all the shows more fully cross-pollinate each other. “Technicolor is about colour separation,” Joffin says. “Not saturation.”

Characterful colour

Though saturation, or at least subdued colours, was exactly what Kingston was after on Black Bird. Recommended for the show by a producer she’d worked with previously, “this was my first television project in which I shot all six episodes. It was a new challenge for me, and I felt very fortunate to have the opportunity to create and maintain the look of an entire series. Leading up to Black Bird, I shot independent feature films, commercials and music videos.

“I shot on the Alexa Mini LF and Panavision H Series lenses. Before I even tested lenses, I had a strong feeling that the H Series would be the ones I’d use to shoot this project. I had used them before on a handful of commercials and fell in love with them. There’s a subdued feeling to the colour palette, a pastel-like quality that I was after and I felt like they were perfect for this.”

As for the specific “this” of the episode submitted for Emmy consideration, “ultimately, I decided on episode three, ‘Hand to Mouth’, because I felt like it was the most representative of the series’ cinematography as a whole. Our two main characters, Jimmy (Egerton) and Larry (Hauser) meet for the first time and the episode mostly takes place in our main prison location. One of my favourite scenes is when Jimmy fights another prisoner in an effort to prove his ‘friendship’ to Larry. This scene stuck out to me when I read the scripts for the first time and I’m really happy with the way the visuals turned out. We lit it all by skip-bouncing ARRI Maxes through the windows and embraced a static camera for much of the scene to build tension.”

Static camera, then, paid off for key scenes in both series. Joffin, by the way, captured his desaturation-to-Technicolor journey on a Sony Venice 2 with Zeiss Radiance lenses. “It was so much fun,” he says of the experience. “I decided to ride the coattails of the amazing production design, the songwriting,” and everything else. “Everyone,” he says, from the actors to the crew, were “so collaborative.”

Which, hey, is usually what it takes to put on a show.

Now, when Hollywood’s studios and producers will once again start collaborating with striking guilds, and those supporting them, so that future shows can go on, remains a very open question. But the clock is ticking. And the calendar pages keep coming off the wall.

Write in, and let us know how your own “strike season” is faring: AcrossthePond@gmail.com / @TricksterInk