It always seems to be one precipice or another, out here on the edge of the continent. As this is being written, both town and country teeter on the edge of several. While the current solvency of the US is being thrashed out in Washington, Hollywood’s own solvency similarly hangs in the balance, as below the line workers have voted overwhelmingly to authorise a first-ever IATSE strike, should the producers not come to some kind of accord on their basic demands, which have even more to do with working conditions, than wages.

As IA President Matt Loeb said in a recent interview with the LA Times (which has pretty much been his only interview, of late), the negotiating points are “meals and breaks during the day; rest periods between shifts and on the weekends; a living wage for the lowest-paid people; and some appropriate adjustments to new media [streaming] based on its maturity.”

None of these seem particularly radical, as labour demands go, but they may speak to a larger reckoning coming perhaps, to both sides of the pond. In an interesting strike update for Hollywood trade The Wrap, actress Frances Fisher, the VP of SAG’s local, said “I think all of us, not just those in IATSE, have been asking ourselves during this pandemic about what we are willing to risk to ply our trade and make our art. And I think we are all now also asking…how much money do these studios need, really?”

Which speaks to something Loeb said in the interview, that studios and streaming companies have “made it about power, not reason, so my read is that if they see that the strike authorization is passed, then maybe they will return to reason and the bargaining table. But if it’s about power, that’s a problem.”

Indeed. But, as with the wrangling in D.C., there would seem to be as much an existential aspect to these struggles as a practical one: Who, ultimately, runs things? Those who do the work, or those do the owning?

It’s an old question, and previous incarnations of the IA would, surprisingly, have been on the ownership side. For indeed, the last time below the line workers walked out, in the mid-1940s, it was called by the more activist Conference of Studio Unions which the IA of the time was opposed to. And in October of 1945, after a few months of protests and pickets, things came to blows – and rocks, fists, tear gas, and fire hoses – in front of Warner Bros. Studios, with at least a couple dozen hurt in what has come to be called “Bloody Friday.”

As the late film historian Nora Sayre noted in an LA Times article that itself is about a generation old, the eventual lockout of CSU from the studios was the final blow “that defeated the CSU and – many thought – the possibility of enlightened unions.” Brewing McCarthyism took care of the rest, as any seemingly reasonable workplace demands could be conflated with being somehow “unAmerican,” all of it with the support of then- IA head Roy Brewer, whom Sayre described as an “impassioned Red-baiter.”

The landscape has certainly shifted since. And on the eve of what became a historic vote – nearly 90% membership turnout, supporting a nearly 99% “yes” vote on strike authorisation – we found ourselves at what might be a modern version of “the hustings,” which for LA, meant the two adjacent parking lots just off Sunset Boulevard, of Locals 600 and 700 – the Cinematographers and Editors guilds, respectively.

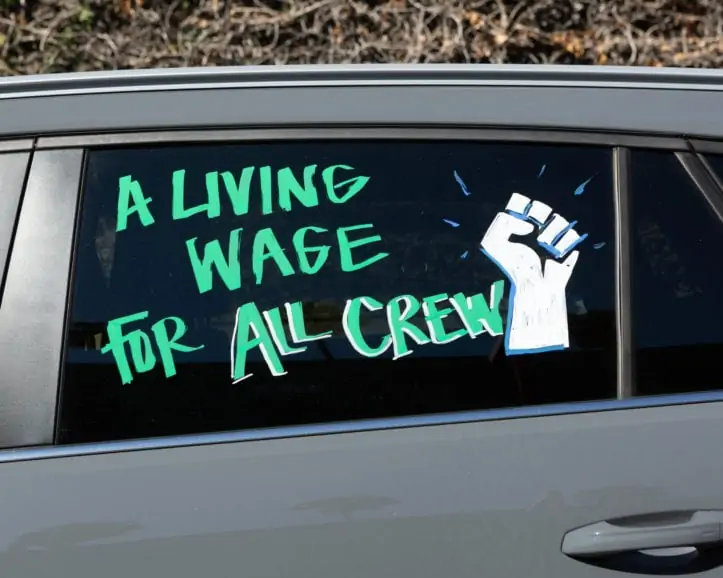

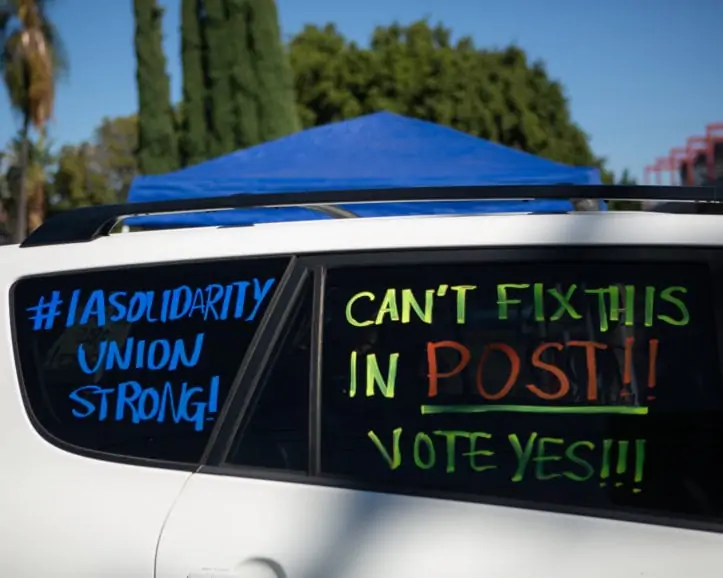

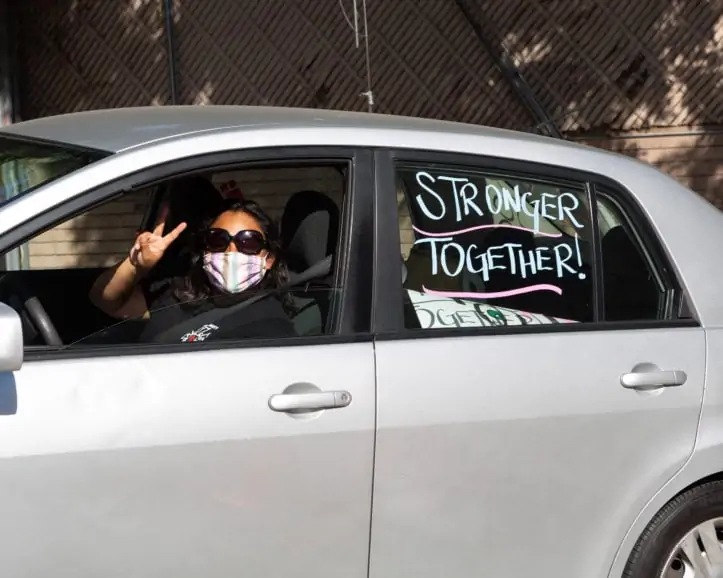

Folks had come there, on a warm Saturday afternoon, for a “Car Painting Drive-Thru,” wherein arriving vehicles would be adorned with slogans like “Your Health, or Their Wealth,” “New Media Is Not New – Just Media,” and “You Can’t Fix This in Post,” along a lot of “Vote Yes!” proclamations, and stenciled clenched fists. Thus would the message be literally taken to the streets, in a city already overrun with cars.

Also present was 600’s National Executive Director, Rebecca Rhine, who echoed both Fisher and Loeb in saying this may be “much bigger than the entertainment industry,” drawing direct lines between Amazon workers in a warehouse, or on sets, or conversely, an Apple employee on an assembly line, versus working on a soundstage. “This is the fight,” she said, “and this is the moment.”

People’s “safety, security and dignity” were not things she felt should be up for negotiation. And as for the authorisation, which wouldn’t be announced for another 48 hours, she added “I have a sense they’ll get an unmistakable message from this vote.”

Which certainly turned out to be the case.

Her counterpart at Local 700, Cathy Repola, thought that the AMPTP would be pretty cognisant of the moment too. “I can’t imagine they wouldn’t be a bit concerned,” she said.

She also noted that longer hours on the set were impacting everyone along the pipeline. “Production hours impact post-production,” she noted, and every aspect of the workflow is “going longer.”

Or as Kurt Russell said in The Thing, “we’re all very tired.” Of course, he added “nobody trusts anybody now,” and we’ll have to see how the rumored resumption of bargaining between the IA and producers ultimately shakes out, and whether going over this particular precipice can be avoided.

Prior to the whole question of whether “the town” will keep working (and “town” would likely include soundstages and sets in places like Georgia, New Mexico, and elsewhere), to provide more “content” for the gaping maw that is entertainment consumption, the more literal “town,” in the Hollywood sense, re-enacted some familiar rituals this past month.

The first of these was the Emmy awards, held in person in that same “more or less” way the Oscars were.

The other ritual was “the trade show,” in this case, in the form of a much-reduced Cine Gear, held not on the Paramount lot, as per usual, but in one hall of the downtown convention centre. It was to be a meeting of British Cinematographer’s editorial and publishing side with this selfsame “Hollywood bureau,” but alas, no visas were possible during that moment of the Delta surge.

And so, this same correspondent wound up drafting his producer’s assistant son, and budding architect daughter-in-law, to help people the BC booth.

The show itself was, at once, all very familiar, and very different. Space here doesn’t permit a fuller recounting, but we’ll get to one on the magazine side soon.

Meanwhile, regarding Emmys, we refer specifically to the Creative Arts side, a series of three different Emmy gatherings – at the same downtown LA Live Microsoft Theater venue – held over two nights and an afternoon, the weekend before the main affair on network TV.

This earlier version, you may recall, honours all the crafts who can’t be squeezed into primetime: production designers, editors, animators, costumers, live broadcasts, even guest stars, and of course, cinematographers.

While this side of the Emmys is usually not in the news as much as its above-the-line counterpart, unfortunately it quickly returned to the headlines when 53-year-old Marc Pilcher, who’d won a statue for his hair and make-up work on Bridgerton, died of COVID a mere three weeks later. It was, needless to say, shocking. All of us who attended, whether back in the press room or nominated, and gathered around the tables in front, had to have been vaxxed and shown a negative test result no older than 48 hours to have gotten in.

So, while there’s no telling yet where and how Pilcher picked up the virus in the ensuing short weeks, whether in LA, on the plane back, or upon returning to the UK, it certainly calls into question the whole decision to have those front-of-housers doff their masks as the cameras rolled, and the show went live.

Luckily, no one else at the awards has reported coming down with COVID since, and while the hair and make-up side of the crafts aren’t our main beat here, Pilchard’s comments on how he took an anachronistic approach to his work, honouring Bridgerton’s Georgian period, while combining it with later, less restrained styles that acknowledge its alternative timeline, remain vivid.

And now he’s gone. Heartfelt condolences to his colleagues and clan.

But even on awards night, some of the already-noted travel restrictions, and general hesitancy, kept many of the night’s nominees – and winners – away.

So it was that the only cinematographer who came backstage, where the dozen-ish or so of we press minions had gathered for the Q&A (all still in our own masks and arrayed at tables where we were all at least “reasonably distanced” from each other) was George Mooradian ASC. He had just beaten out his pal, the thrice-nominated Donald Morgan ASC in the “Multi-Camera Series” category.

He was amazed to have done so, calling Morgan a “triple threat,” and noting that Donald had gotten a room there at the Ritz-Carlton (as with the Oscars, the press facilities were in the hotel next door to the hosting venue), where some congenial carousing was going to ensue (regardless of who actually won).

Mooradian’s winning show was Netflix’s Country Comfort, about an aspiring country singer who takes a nanny job to a single-dad cowboy and his clan, from which a musical act emerges.

You can practically taste the pitch for that one.

Mooradian, who had figured Morgan would win the category again, was very gracious to the man he credits for getting him into the TV side of the biz in the first place.

He also thanked Jim Belushi, who he met, courtesy of Morgan, when the actor’s series According to Jim was prepping. At first Mooradian – who’d shot a lot of indie features – thought “I have my art.”

Then again, Belushi asked what he’d thought about regular hours (perhaps a tad more regular then, than the conditions driving the current strike vote), and being able to see his family.

Mooradian considered his gaps of being away for eight month stretches, and finally assented to give it a try. Only to hear back that “ABC wouldn’t hire me (saying) ‘he’s never done this before!’”

But eventually it worked out, starting with very provisional “day to day” contracts. He’s subsequently worked on shows that Morgan is known for, like Last Man Standing, and had been nominated for Emmys numerous times, including for According to Jim, only to finally score his first win now.

Like his friend and colleague, Mooradian also talked about taking the same filmic approach to his work, using “Glimmerglass, different gels…I’m a big believer in lighting and figuring out a set without fill light – I kill the bounce light, and then I try to be sourcey. Too many sitcoms (think) it’d be safer to put everything on the grid.”

He also tries to find “more cinematic compositions,” often framing himself on stage first, instead of defaulting to “composing center frame (which is) not very interesting.”

He acknowledged that sometimes “it doesn’t work,” but when he, like Morgan, gets a note that “it’s too dark – that means it’s real.”

The darkness is indeed more palpable as we head into winter. Further reports on the temperature of things coming soon.

Until then, AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com / @TricksterInk