LYRICAL LIFE STORY

Part musical, part biopic, tick, tick…BOOM! details the struggles and successes of a composer and playwright at a pivotal point in life as he navigates life and strives to fulfil his creative ambitions. In telling Jonathan Larson’s story, Alice Brooks ASC and director Lin-Manuel Miranda explored blurring the line between dreams and reality and infusing music with visuals.

“Whilst shooting In the Heights, I found myself falling in love with Washington Heights. Making tick, tick…BOOM!, I fell in love with Jonathan Larson,” says Alice Brooks ASC about her time lensing two hit musicals in 2021.

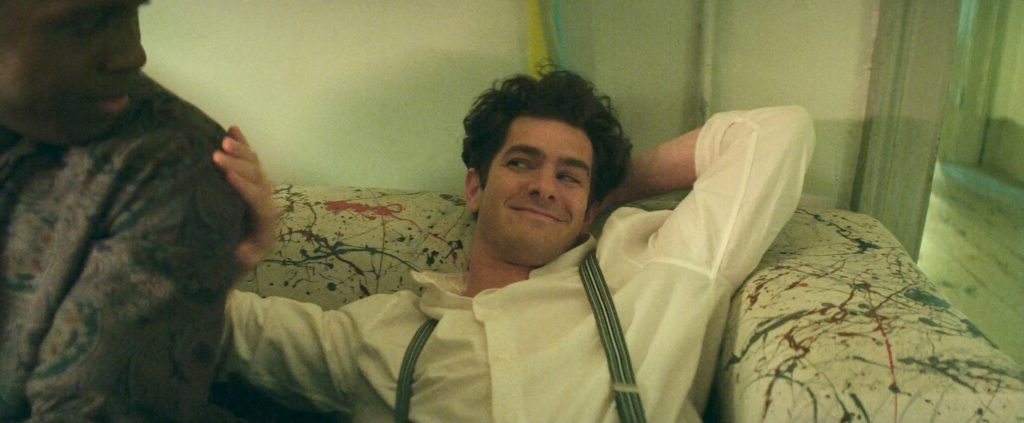

The cinematographer’s latest production – tick, tick…BOOM! – follows the inspiring life of Larson (played by Andrew Garfield) – an aspiring songwriter and playwright dedicated to his craft who went on to write award-winning Broadway musical Rent. Tragically, he passed away the night before it premiered.

The film centres on a crossroads in Larson’s life when he is approaching 30 and writing an autobiographical one-man show about the struggles he is facing whilst trying to get his work produced. tick, tick…BOOM! is adapted from that early musical – a rock monologue, a portrait of an artist with creative passion, and a love song to musical theatre. It charts Larson’s determination and the battles he faces whilst navigating life as an artist in pursuit of his dream.

Brooks grew up in New York with her playwright father and dancer mother in an apartment similar to Larson’s. “It was filled with creative people, and we lived a bohemian lifestyle,” she says. “When I read the script for tick, tick…BOOM!, I thought they could be scenes from my childhood.”

The cinematographer compiled images for her meeting with the film’s writer-director, Lin-Manuel Miranda, whom she met while shooting In the Heights, directed by Jon M. Chu and based on the hit Broadway musical Miranda wrote when he was a student.

When Brooks showed Miranda her reference images for tick, tick…BOOM!, many from her childhood, he said, “Well, it doesn’t get more personal than this.”

In 1990, when the film is set, Miranda and Brooks were both around 10, and the director wanted to adopt a “child’s eye view of New York”. “We had the same perspective…Alice’s family moved from New York in 1990, so her memories of that era are frozen in amber,” he says. “When she showed me photos of her childhood apartment, I thought that’s the look of our show – a pre-Disney Times Square New York, saturated and filtered through our VHS memories.”

This childlike perspective of the city where light, colour, and emotions are heightened became the starting point for Miranda and Brooks. From there, they explored how to blur the line between dreams and reality.

Larson is the artist that made Miranda feel it was possible to write musicals. “Seeing Rent for my 17th birthday gave me permission. It was the most contemporary score I’d heard; it had the most diverse cast I’d seen, and it felt deeply personal,” he says.

The Off-Broadway version of tick, tick…BOOM! documenting Larson’s own struggle to be heard and to connect which Miranda saw when he was 21 years old felt even more personal: “Those shows planted a seed in me at a very formative age, and making this film felt like a way to honour and thank Jonathan for changing my life.”

First-time film director Miranda brought valuable experience gained from his time in the theatre world. “He knows how to workshop something, to try it over and over again,” says Brooks. “So, there were many more rehearsals compared to most movies.”

Brooks treasures the time filmmakers can spend with the actors when working on a musical because it makes cast and crew become like a family. Listening to the pre-records to start to understand what the performance will become allows the music to infuse with the visuals. “This means it doesn’t feel like you’re suddenly in a musical number – the transitions feel organic as we’ve created the space for the audience to be in the story,” she says. “When people reference tick, tick…BOOM! as a biopic more than a musical, it’s a huge compliment because it means the musical is telling the story rather than forcing it.”

Each song is a journal entry

Miranda, Brooks, and production designer Alex DiGerlando were inspired by the extensive amount of video footage of Larson they had access to, motivating them to open and close the film with archive-style Betacam shots of Garfield. “We wanted to bring that 1990s video quality to parts of the film and for it to have grain, texture, and often muted colours,” Brooks says.

Colour inspiration for other scenes was drawn from New York street photography including the stunning work of Nan Goldin and its desaturated palette. tick, tick…BOOM! is set against the backdrop of the AIDs epidemic and captures a bleak time when many of Larson’s friends are getting sick. Brooks used green hues from one of Goldin’s photographs of HIV patients for a scene in the hospital to reinforce that this time in Larson’s life was neither colourful nor vibrant.

“Nan Goldin’s work has been referenced as a private photo journal made public. That’s what tick, tick…BOOM! was for Jonathan,” says Brooks. “He got to write his life story five years before he died and now it’s being made public, so I feel like each song is a journal entry.”

Many musicals are about dreams and those are the stories I love to tell the most.

Alice Brooks ASC

During the detailed period of research, DiGerlando and the art department referred to video footage Larson captured detailing every object in his apartment, allowing them to create a replica of his home, complete with art-covered walls.

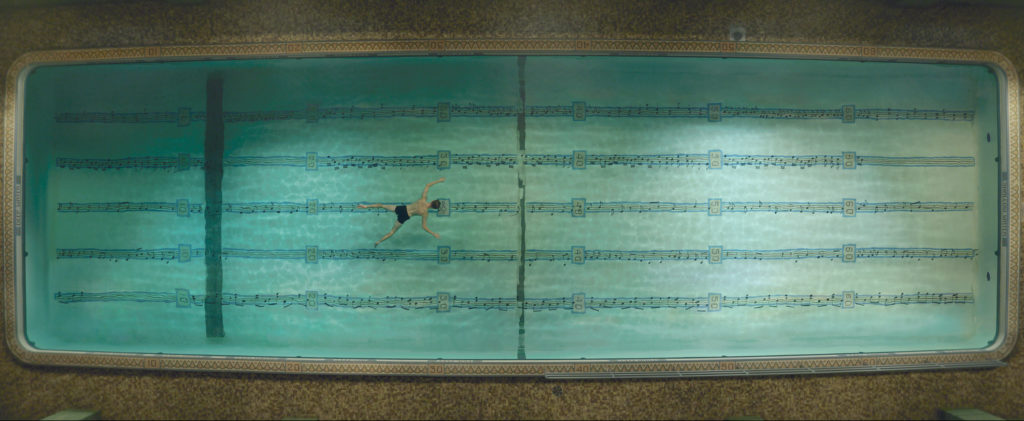

When searching for a swimming pool to use for a scene accompanying the number Swimming, Brooks and Miranda made another discovery when they found a beautiful pool in New York which turned out to be the pool Larson swam in. Miranda was drawn to the pool floor which aptly resembled music manuscript paper. When Brooks dunked her iPhone under the water to record test footage, they discovered a perfectly positioned 30 at the bottom of the pool.

Lin suggested that when Garfield touches the 30 – the age Jonathan is scared to reach – it could transform into a treble clef. “I love that it’s a visual representation of a single moment of genius for Jonathan and it also felt like a moment of genius for Lin when everything came together,” says Brooks.

The underwater sequences were skillfully captured by Sean Gilbert, an underwater operator Brooks has previously collaborated with. During prep the cinematographer and Gilbert went through the storyboards and the animatic that Brooks had created. They worked with key grip, Kevin Lowry, to decide which tools to employ for the sheer number of shots they needed to capture. “For example, Sean worked with the underwater grips to create a pulley system whilst operating under water. And Kevin built scaffolding in the pool for the Chapman underwater crane to track along the side of the pool, for all the bird’s-eye shots, and shots where the camera starts above water and dunks underwater.”

Referring to footage of Larson at the diner he worked at was beneficial when recreating the location for one of the film’s significant and most elaborate numbers, Sunday. The plan was to incorporate a stellar line-up of Broadway legends into the scene, sitting in the diner. During a storyboarding session, production designer DiGerlando demonstrated a model of the diner set and took down the wall, inspiring Lin to suggest it became a stage. “At times like that, we felt like Jonathan was whispering in our ear, telling us what we should do,” says Brooks.

For Miranda, the most exciting part of the collaboration process was the storyboarding and scouting. “We made a lot of decisions about how to ‘bring home’ the numbers, the handheld cameras for real life versus the Steadicam for the fantasies in Jonathan’s head,” he says. “I learned so much about how Alice uses light, both natural and the stage lights within our concert framing of the film. We used every musical number as an opportunity to expand the visual vocabulary of the film.”

Intimately familiar with the music

When tick, tick…BOOM!’s momentum was halted by the pandemic Brooks dedicated much of this time to listening to the pre-records – the music feeling so relevant to the situation the world was facing. “While Jonathan was living through the AIDs crisis and losing his friends, that’s very much what the pandemic felt like,” she says.

“Dreams were also moving further away. It was devastating when we got shut down and didn’t know if we would get to finish the movie. At first, I couldn’t listen to the music, but after a month I thought, we’re making this movie and I’m going to listen to the music every day. 30 years later, Jonathan’s lyrics are still so relevant. ‘Why does it take a catastrophe to start a revolution?’ could also relate to many moments in 2020 and this moment in time when it feels like a real change is happening.”

Returning from the pause in production, scenes had to be storyboarded again while the musical numbers’ storyboards remained intact. Brooks cut the animatics, something Chu had done when they collaborated on In the Heights. “I became so much more intimately familiar with the music through doing this,” she says. “Every choice I made on tick, tick…BOOM! was so specific and I believe that’s partly because I cut the animatics.”

When production resumed, Brooks also discovered she would not be allowed to use atmosphere due to COVID safety protocols, making shooting scenes of 1990s stage shows challenging. “Especially as all our camera tests had been shot with atmosphere, and I like to use it to add an aged quality and lower contrast,” she says.

As well as detuning lenses further to help achieve the effect she had wanted to accomplish with atmosphere, Brooks added a 1/8 Tiffen Black Pro Mist filter and additional visual effects smoke were applied to some shots in the New York Theater Workshop. “It was far more expensive than doing it practically but much safer for the crew,” she says.

While live singing is a joyful experience when making musicals, adhering to pandemic regulations placed additional demands on the cast and crew who had to wear plastic gowns when live singing was taking place, plus the usual face shields. “For a Steadicam operator in particular, it’s really tricky being in a hot plastic gown and being unable to move your body in the normal way,” says Brooks.

But despite the challenges faced on this occasion, the freedom live singing offers shone through. Instead of being locked and rigid, the camera must be fluid and flowing. “There’s this beautiful dance between the camera and actor with live singing versus a pre-record and spontaneous things happen you never could have planned,” she continues.

The “technical storyteller” capturing this “beautiful dance” was Michael Fuchs, a Steadicam operator who Brooks says, “loves being part of the process; really engaging, watching, and listening to figure out the best way to approach a scene, whilst offering his own ideas.”

“Whip pans had to be timed precisely for a certain note. Getting that right is tricky, but Fuchs mastered it because he really understood the music. Similarly, key grip Kevin Lowry – who I’ve worked with twice before – was such a joy to collaborate with. He’s like another pair of eyes for me.”

tick, tick…BOOM! also introduced Brooks to DIT Abby Levine, a key collaborator she hopes to team up with on future productions. “He’s an amazing technician and wanted to be so involved in prep. He would often watch the dailies with me and donated so much time to make sure everything was set up exactly the way I wanted and that the look was completely followed through at every stage.”

The action in scenes taking place on stage in the theatre setting – apart from the more static, structured number Therapy – was captured handheld. But when prepping these sequences, they were initially designed as large sweeping shots with complicated camera movements. “We then realised that was the wrong choice because we didn’t want to make the viewer feel like an audience member watching in the theatre,” says Brooks. “We wanted them to viscerally feel what Jonathan was feeling on stage which we achieved by shooting handheld and changing the lighting slightly for each number.”

Miranda agrees the challenge in any movie musical is negotiating the audience’s relationship to the musical numbers. “When you’re seeing a piece of theatre, there’s a proscenium, they’re on stage, and we are all in a shared contract of make believe,” he says. “Movies look like real life: to ease an audience into our characters bursting into song requires considerable care in execution. We used Jonathan’s concert as the frame: he is singing us a song and accompanying himself on piano with a band, a naturalistic way in. But then, after the first chorus, we cut into a dialogue scene at the diner, but never stop the music: we understand we’re in Jonathan’s story.”

Posing questions

When shooting the lyrical life story, the overriding aim was to be close to Garfield. Filming him from behind became a recurring theme. Brooks also likes to pose a question to motivate the camera. On this occasion it was, ‘What do we do with the time we have?’ “It was really important that when Jonathan is in his apartment trying to write music for it to feel cramped, but then when he goes outside for the audience to feel the whole world around him and the possibilities that were open to him,” she says.

Like every production Brooks lenses, choosing the camera and lens needed to tell Larson’s story was an intuitive process. Having asked Miranda how involved he wanted to be in those choices, the cinematographer was delighted when he responded, “I want to know everything.”

“He just loves to learn which I was so happy about,” she says. “So, I shot tests and we met at the lab to project the footage. It was a blind test because Lin has no connection to any of the manufacturers which was really refreshing.”

First, they determined whether Miranda liked spherical or anamorphic before looking more closely at camera and lens selection. Brooks returned to the Panavision DXL2 – the model she shot her previous three movies with partly due to its rendering of out of focus light and flares. “What I liked most on this movie, and the reason we ended up picking the camera, was the unusual shape of the bokeh when it was paired with the Panavision G Series.”

Brooks has shot with the Panavision G Series anamorphic lenses previously but “always changes the recipe”. This time around, they were sent to Panavision’s Dan Sasaki for detuning. “As a piece of anamorphic glass, the G Series is fantastic,” she says. “Not crisp but not too mushy and you can shoot fairly wide open. I felt like a portraiture approach with less depth of field was right for the spaces we were shooting.”

Whereas In the Heights was illuminated with LED fixtures, tick, tick…BOOM! followed a hybrid approach to lighting, with gaffer Bill O’Leary selecting a combination of tungsten fixtures such as ARRI Studio T12s and LED products – including ARRI SkyPanels for night-time scenes on the roof and Chroma-Q Color Force strips as a car pass source – as well as a handful of HMIs. “It was a dance with light dictated by the story,” says Brooks.

When deciding on the approach for the scenes on stage, O’Leary and Brooks felt they needed to honour the time period and Larson’s situation. As he had little money to produce his show, the most suitable choice to ensure the scene’s authenticity was using old PAR CANs.

In the last few days of the DI, Brooks asked O’Leary if he wanted to sit in on it. “I wanted him to see the beautiful work he had done. Prior to this, nobody had invited Bill to a DI in the 30 years he’s been a gaffer,” says Brooks. “He had many questions and found it such a valuable experience which made me think I should always make sure the gaffer is invited to the DI, so they can grow and learn too.”

The grade saw Brooks reunite with Company 3 senior colourist Stephen Nakamura for a third time. “We coloured this film in a totally different order to my previous films – because it’s Netflix, we started on the HDR pass and then went to the P3 pass,” says Brooks. “On the HDR pass, you’re just colouring on a 32-inch monitor, but when you see the P3 version projected on a large screen you notice new things, some of which I preferred.”

Brooks felt HDR was “too vibrant” for the look 1990s she was aiming at for tick, tick…BOOM! Instead of using the full HDR range, it was squeezed down to around 600 nits. Nakamura also introduced Brooks to DaVinci Resolve’s Colour Warper to desaturate the colour whilst retaining skin tone in a scene accompanying the number No More. LiveGrain was also added to “muddy up” the image and create another layer of texture on the P3 and HDR pass.

Being a life-long fan of musicals, Brooks is delighted to be shooting another next year when she lenses Wicked with director Chu. So, what is it that makes them such a joy to create? “There’s an energy, joy, and commitment from everyone involved. Working with incredible leaders such as Lin and Jon sets a wonderful tone. There are no egos.”

For Miranda, musicals are “like real life, but better” and making tick, tick…BOOM! stands out due to the close collaboration that helped bring the film to the big screen. “Alice and I developed such an incredible shorthand that we were basically subverbal by the end of the shoot,” he says. “I could look at her and she’d say, ‘I know, we’re fixing it.’ That level of collaboration arrives when you’re in total lockstep.”

Working with extraordinary source material is also a constant source of inspiration for Brooks: “tick, tick…BOOM! and In the Heights are both about dreamers but they explore the story in different ways. Many musicals are about dreams and those are the stories I love to tell the most.”