ADVENTURES IN BARBIE LAND

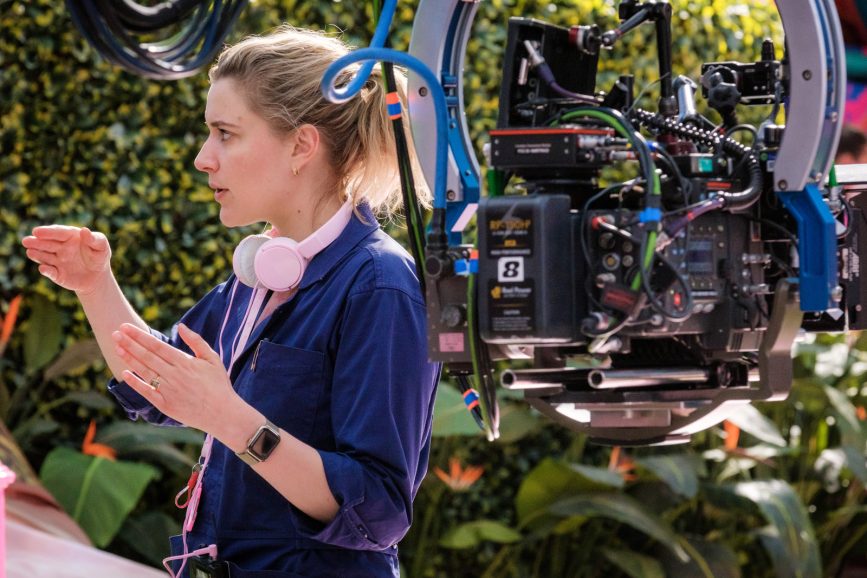

It will have been difficult to miss the film frenzy as the Barbenheimer craze swept the world and crowds rushed to see two very different but captivating releases on the same weekend – Oppenheimer and Barbie. We take a trip to Barbie Land with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC to find out how he helped make writer/director Greta Gerwig’s concept of “authentic artificiality” a reality.

As well as enjoying the most lucrative opening weekend of the year, Barbie is a landmark release, boasting the highest-grossing opening for a female director. Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC, the Mexican cinematographer helping realise the bold vision of writer/director Greta Gerwig, describes the Barbie buzz as overwhelming. “I anticipated people would want to see it and there would be high expectations, but I never imagined this. Everybody’s going to the cinema dressed in pink – it’s phenomenal,” he says, speaking to us from Mexico City where he is in the edit for Pedro Páramo which he directed and co-shot.

When Prieto received Gerwig’s initial call about Barbie, he was in Oklahoma prepping Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, another production set to continue the cinematic buzz with its October release. “Any film Greta called me about I would have jumped on – I already admired her work and was drawn to her energy on the occasions we’d met,” he says. “I was intrigued a director like Greta would make a film about Barbie that seemed so different to previous productions she’d written and directed (Lady Bird, Little Women). But I knew it would be different to what you’d expect, and casting Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling as Barbie and Ken sounded like a perfect fit.”

Aware he would also explore a different visual world to his past work which includes The Irishman, The Wolf of Wall Street, and Brokeback Mountain, Prieto was even more eager to jump on board creatively as a cinematographer and personally. “I grow when I participate in projects that stretch my creativity or push me in new directions. On a personal level, I get to experience different views on life; and as a cinematographer, I keep searching for new ways to express myself visually. Greta and I both love cinema and making movies, and she’s so enthusiastic, it’s contagious.”

As a writer and a director, Gerwig is always looking for a fun challenge. “As with Little Women, Barbie is a property we all know, but to me she felt like a character with a story to tell, one that I could find a new, unexpected way into, honouring her legacy while making her world feel fresh and alive and modern,” she says.

It was evident the bold and bright world of Barbie Land where much of the action takes place needed to be captured on stage while the real world which Barbie and Ken later explore after Barbie suffers an existential crisis would be filmed in Los Angeles. Other than sci-fi Passengers (2016), Prieto had not worked as extensively in a studio, but he was excited at the prospect of being largely stage bound.

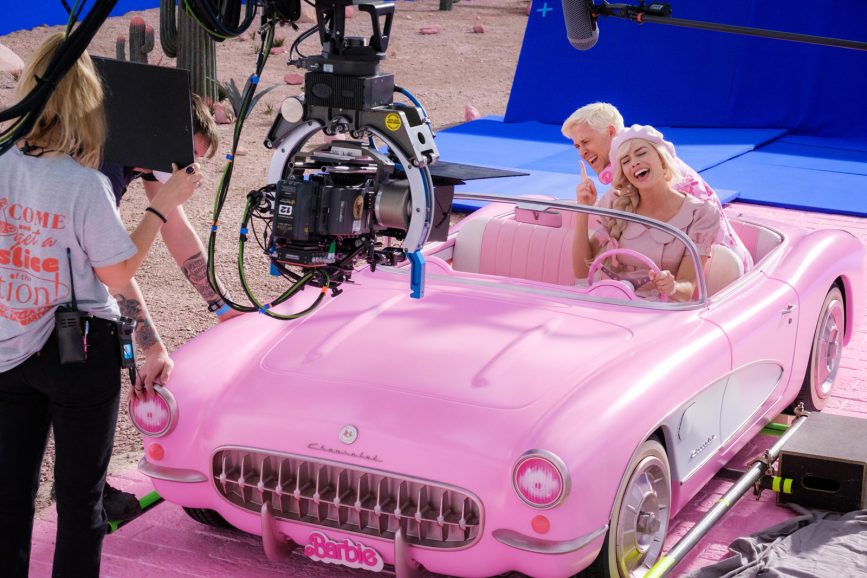

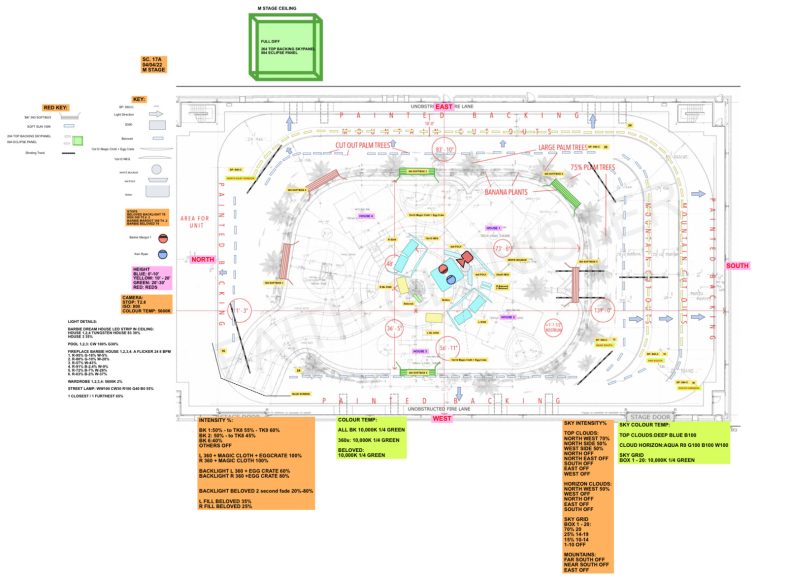

Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden was turned pink as Barbie Land took over eight of the stages and backlot. Designed by Oscar-nominated production designer Sarah Greenwood (Atonement, Anna Karenina), the stunning sets included Barbie’s iconic Dreamhouse, Weird Barbie’s house, and an expansive beach set among numerous other interior and exterior locations. The movie reportedly required so much of Rosco’s signature fluorescent fuchsia paint it led to a global shortage.

Colourful journey

Gerwig shared her concept of “authentic artificiality” for Barbie Land and creating a world that still had a feeling of naturalism. “When embracing the artificiality, we constantly straddled the line of is it a toy world, are they inside a box, or is it real?” says Prieto.

Colour was a logical starting point. Prieto showed Gerwig and Greenwood samples of a vivid Mexican pink (or rosa mexicano in Spanish) he felt should be included in the environment. Gerwig wanted Barbie Land to feel like a happy place “where Barbie lives in our childhood imaginations. As a little girl, I liked the brightest pinks, but Barbie Land would incorporate the full spectrum of the colour, so it was important to figure out where those bright pinks would live alongside our palest, pastel pink, and of course every tone of pink in between,” says Gerwig.

Colour exploration led the filmmakers to create six show LUTs including three main LUTs – Real World (a neutral film emulation look); Techno Barbie (inspired by the three-strip Technicolor process used on classic MGM musicals); and Half-Techno Barbie (a half strength version made for Weird Barbie’s house). A volume version of each LUT was created to match the stage work and to compensate for the limited colour spectrum output of the LED panels in the virtual stage. “It’s a whole different colour space in the volume stage, but we set out to bring it as close to our LUTs for Barbie Land or the real world,” says Prieto.

Prieto’s frequent collaborator, Company 3 colourist Yvan Lucas, joined him in the LUT experimentation, continuing the journey they began on The Irishman (2019) developing grading software PPL with Philippe Panzini from Codex. The software, which they used extensively on Killers of the Flower Moon, allows control of elements such as brightness, intensity, hue, and saturation of each colour.

“Instead of windowing, we could create LUTs and play with colours,” says Prieto. “When I did Killers, we created a LUT that emulated Technicolour and based on that LUT we experimented to make something specific to the colours of Barbie Land. Greta also loves many of the movies from the ‘40s and ‘50s shot with Three Strip Technicolor, so it was perfect to use it as a basis to create our LUT for Barbie Land.”

Testing with production designer Greenwood and costume designer Jacqueline Durran involved creating a simplified version of a set combining panels and costumes in the movie’s key colours to represent Barbie Land. Shooting a stand in allowed them to test skintone which could be affected by the bright hues and become oversaturated. The picture perfect LUT for Barbie’s world used fewer variations of colours to appear more childlike. Knowing it was based on Technicolor, Gerwig suggested the LUT should be called TechnoBarbie.

As the visual approach for Barbie and Ken’s experiences in the real world was simpler and needed to feel more familiar, a LUT was created to emulate the Kodak 5219 stock – “something cinema goers are used to and feel the real world should look like.”

A tale of two worlds

Prieto felt camera language could express ideas Gerwig wanted to explore and distinguish between the two environments. “What the camera does or where it is, to me, is dictated by the emotional moment of the character. So, in Barbie Land, if this were a perfect toy world a camera would behave with simplicity and innocence. To me, that meant avoiding oblique angles or long lenses,” says Prieto, who aims to make his camera work subjective, basing choice of angle on the character being focused on and how they might feel.

“Framing in Barbie Land was in line with how a kid would look at a toy. When they open a box, they see the Dreamhouse front on, so we thought of framing with the mindset of a child.”

During detailed storyboarding and shotlisting Prieto suggested as well as being mostly frontal or sideways, the approach should be physically close and somewhat wide angle. In the picture-perfect Barbie Land, camera movement would follow suit using linear moves to “track perfectly sideways or forwards with a character or vehicle.”

“Camera moves had to be perfect in the sense it couldn’t go slightly on a diagonal, or bump around because in Barbie Land, everything and every day is perfect,” says Prieto. “Like Barbie, the camera had a routine, but when things start to go wrong for Barbie, the camera doesn’t “know” this, so it continues doing the exact same thing every day, so when Barbie falls, she also falls out of frame and the camera doesn’t follow her fall.”

As the Mattel boardroom Barbie visits was a symmetrical set, the Barbie Land camera language continues, with every shot frontal and balanced. “For Barbie, it’s home and she thinks that as her creators, Mattel are the good guys, so we continued that language,” adds Prieto.

As well as being Gerwig’s first digital shooting experience, Barbie was her first venture into the 2:1 aspect ratio. After toying with 1.85 or 2.40 anamorphic they felt although 2.40 is cinematic, it might be too sophisticated. While 1.85 might be suitable for vertically framing Barbie’s body and Dreamhouse, shots of the beach and Barbie driving would benefit from wider aspect ratio. So, Prieto suggested 2:1 because “it’s simple, innocent, and easy to frame a head to toe shot of Barbie but still see the environment around her. It also allows for horizontal space in scenes towards the end featuring all the characters.”

During the three-month pre-production – which included experimenting in the London studio, scouting LA, shotlisting and working with storyboard artists to decide how to accomplish shots – the filmmakers contemplated shooting the real world handheld and even shooting on film, but it was decided it might separate the two worlds too much. They allowed themselves to use telephoto lenses, which they didn’t in Barbie Land, and sometimes adopt a slightly more distorted wide angle, as well as “imperfect” camera moves.

Innocent imaging

Before Greenwood finalised the colour palette for production design elements, screening movies and looking at reference images helped the filmmakers form design and colour ideas. Inspiration from still photography included the colourful work of French artist and fashion photographer Guy Bourdin to help determine the Barbie Land look and the street photography of Garry Winogrand for the real-world sequences.

Movie influences encompassed the vivid colour in Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) which takes place in a real town that feels artificial and featured some costumes that match aspects of the background. Prieto also learnt lighting lessons from the film: “I embraced the idea of frontal light to create an innocent feeling as I felt that dramatic sidelight wouldn’t be suitable for a toy in Barbie Land. However, lighting creates the illusion of depth and dimensionality on a flat screen, so if you’re front lighting, you lose that. Therefore, we looked at how to separate characters from the background using colour, backlight, and depth of field.”

The dream ballet in Singin’ in the Rain (1952) inspired the lively sequence which sees multiple Kens dance in unison. The scene was lit with one 200k SoftSun and through full grid cloth diffusion, as the colours changed between cyan and pink. “The SoftSun created beautiful shadows on the floor,” says Prieto. “Some of my favourite shots are top angles where the dancers’ shadows extend the choreography onto the pink and blue floor.”

Actor, dancer, and choreographer Bob Fosse’s style also impacted the design of such sequences. His choreography was intended for one camera as many dance sequences in Barbie would be. Prieto commends Barbie choreographer Jennifer White for being “cognizant of the idea of creating choreography for the specific camera positions.”

An impressive set built for the brightly coloured house in Jerry Lewis’s The Ladies Man (1961) informed Barbie’s Dreamhouse design due to its fourth wall approach making the audience feel like a spectator watching the action unfold in the dollhouse-like space. The Truman Show (1998) – which sees the action similarly take place in an artificial world – made an impact on Gerwig who asked director Peter Weir to share insight into his process of creating “artificial authenticity.”

One complexity encountered during pre-production was determining how to technically “create a miniature world that’s not actually miniature, and make it feel like it’s a fake but real world” while incorporating visual effects and miniatures within the schedule constraints.

“At one point we discussed doing a lot of it with miniatures but there wasn’t time to build all of them. Greta wanted it to feel like you were somewhere triple the size of a conventional soundstage but also felt like being in a box. We harked back to The Wizard of Oz and movies of that era such as The Red Shoes, Oklahoma, Singing in the Rain where you feel the painted backdrops,” says Prieto. “Usually you try to avoid that, even on a stage. But we embraced it. To create a believable world, the audience needed to feel the painted wall at the end of the sets.”

With these references in mind, everything in Barbie’s Dreamhouse and surrounding cul de sac was meticulously created by the production design team, from the painted backdrop and palm trees, some of which were three dimensional, through to mountain cutouts deeper in the background. Lighting behind the mountains could illuminate the sky different colours. Sets that were too small such as the beach required blue screen techniques and visual effects extension.

“I’m in love with 1950s soundstage musicals, those wonderfully artificial spaces, and because Barbie was invented in 1959, it felt like we could ground everything in that look and not be so beholden to it,” says Gerwig. “I want everyone to feel like they can reach up to the screen and touch everything, because that’s the great thing about dolls and toys.”

Although transition scenes which see characters travel from Barbie Land to the real world using multiple modes of transport were outlined in the script, how they would look was yet to be decided. The “innocent camera” that moves forwards or sideways was discussed as was a scene in Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train (1989) which sees a simple head to toe tracking shot as the camera moves sideways.

“I thought we should also photograph our cars using sideways transitions rather than create a set that goes around on a turntable. Based on that notion Sarah took it to the next level, creating something very theatrical based around different layers including a 2D rendition of the car, boat, or spaceship, which is a cut out but had a little volume,” says Prieto.

“In the foreground the wheels turn, and the road moves, but in the background there’s a mountain layer, a painting of distant mountains and sky, with everything moving at different speeds. It feels like there’s depth, but it’s all an illusion with no VFX. It was fun to figure that out in pre vis and decide the field of view and positions of each layer so I could choose a lens. It was very mathematical.”

A magical feeling

Having never shot digitally, at first Gerwig was a little sceptical about making the move, but Prieto felt the look aligned with the concept of authentic artificiality because “a digital camera has no grain and virtually no texture, and therefore feels less gritty.” They explored the idea of “a toy world that looks miniature, but also regular size”, with Prieto feeling the depth of field captured by a large format camera combined with wider angle lenses could give the impression of photographing a miniature.

Gerwig was unsure because she wanted the sets to be visible, so camera testing involved a miniature version of the set being built, the size a Barbie doll would live in, with a backdrop separated into different shades of pink, cyan and yellow. Prieto photographed a Barbie doll with a 35mm lens on a variety of cameras at a specific distance to the doll and to the background and then scaled it up to shoot a stand-in on the real set.

“I used the matching field of view with each camera, so it was an identical shot of Barbie with the same colours in the background as the human stand in on the full-sized set. That’s when Greta fell in love with the ARRI Alexa 65 as its depth of field made it feel closer to shooting a miniature and in her words it ‘felt a little more magical’. Sometimes the sets and colours could be garish (such as Ken’s Mojo Dojo Casa House), so this softened it a bit.”

Lens testing was just as comprehensive, with the Panavision System 65 lenses – originally created for Ron Howard’s Far and Away (1992) – coming out on top. “They’re large format but without an overly sharp feeling. They offered the right combination of resolution, with some details softer but still in focus,” says Prieto. “Greta also didn’t want a vignette making the edges of frame fall off into darkness and liked that the whole frame of the System 65 was even.”

In Barbie Land the Technocrane was in constant use, with key grip Jac Hopkins’ expert knowledge and skill proving essential. “His work was impeccable, and he was always on the pickle to achieve the perfection of camera movement needed. A camera and Steadicam operator Chris Bain Assoc. BSC was also excellent – together with Jac and focus puller Max Glickman, they were like one person. The crew in London were a revelation – I felt so supported. The camera came alive, and I was blown away by the excellence of the grip and camera department. Although it was mostly a single-camera movie, we also had a great B camera operator in Simon Finney,” says Prieto.

“When shooting digital, I don’t like to operate because when shooting on a film camera, you have an eyepiece and an optical sense of the scene. With digital capture you use a little monitor, so I prefer to look at a calibrated monitor with a proper LUT in the tent with the DIT.”

It’s always sunny in Barbie Land

Lighting rule number one in Barbie Land was everything should be backlit. “It’s always sunny, with the sun behind the actors in relation to the camera, so it’s always backlit and the faces always look great,” says Prieto. “And in the perfect yet absurd world, if the camera turns, the characters are still backlit. We would sometimes dim out one SoftSun while another one was dimmed up as the camera panned to a different angle so that it would remain backlit in both directions.”

As sets were built and lighting tests were carried out, Prieto discovered light bouncing off the pink sets made the actors’ faces look magenta. But if he colour corrected and removed pink from the faces, the power of the pink in the sets in the background would be lost. “So, we draped everything off camera with grey material to avoid colour bounce. When you use negative fill, you create more contrast, but using grey kept the bounce, but neutral in colour,” he says. “After eliminating colour bounce, I could build the lighting using big sources to create the fill for the faces.”

While normalising the skin tone was partly done practically by draping grey cloth in the set to nullify some of the pink, the rest was countered with the help of DIT Laura Redpath by piling in several points of Blue and Cyan in Livegrade, while striking a balance of not cooling the tones too much.

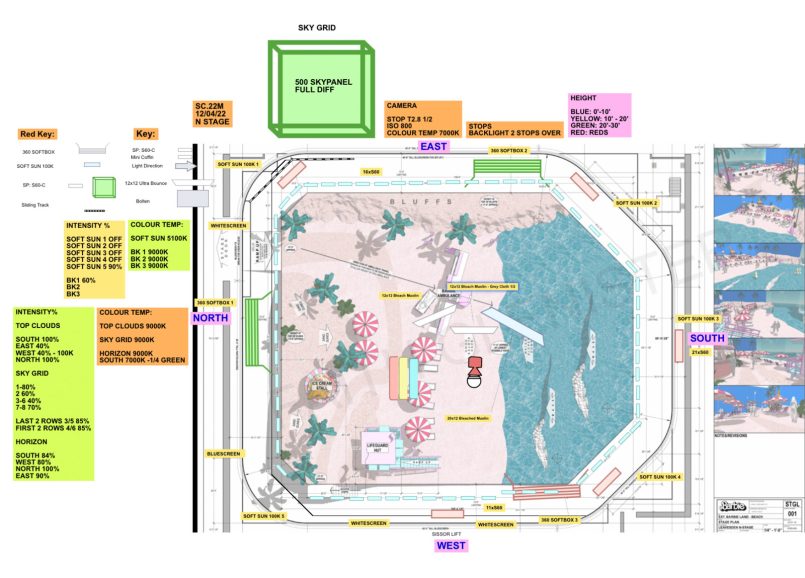

The Warner Bros. Set Lighting & Rigging team provided production lighting and rigging for all shooting at the studios, supporting gaffer Lee Walters and his team in bathing each stage in an iconic Barbie Land glow.

Although blue screen was used rarely, it was necessary for a large set piece which sees the Barbies being deprogrammed in a café and a transition sequence between the pink brick road of Barbie Land and the real world.

To create sky light for many of these day exterior sets the rigging team made soft boxes across the full expanse of each soundstage ceiling, comprising hundreds of Prolights EclPanels and diffused by full grid cloth.

“Lee Walters is an amazing gaffer and introduced me to the excellent Prolights EclPanels which were also cost efficient. This was important because we needed hundreds of them,” says Prieto. “The whole lighting team was exceptional including dimmer operator in London, Kester McClure.”

The large sky light allowed them to control the colour and brightness of Barbie Land with backlight created using 100k SoftSuns. Four SoftSuns were rigged in the stage ceiling of the cul de sac and Barbie’s Dreamhouse set, sometimes using a small track to adjust the backlight position. Changing gels to create different times of day was time consuming, so the SoftSuns’ colour temperature was kept at 5,600k. To make them look warm, the rest of the lighting was made blue or cyan, and compensated for on the camera through colour temperature adjustments.

“SoftSuns were a key part of our lighting and although they seem to light everywhere, they have a sweet spot, so you need to be able to tilt them,” adds Prieto. “For a night scene on the beach where the Kens play guitar, instead of a neutral top light, we shifted it to a turquoise colour we picked for night. For a shot looking at the fake ocean, I wanted a little reflection on the plastic water, so we turned the SoftSun to 1% – as low as a dimmer goes – but it was still too bright, so we put a big double net on it.”

Shooting much of the action on stage meant the crew had space to often use Briese umbrella lights, typically on a stand or on a condor lift on sets such as Barbie’s Dreamhouse. “It’s huge and round and a pleasing light for faces because the shadow is rounded out,” says Prieto. “It’s the perfect cosmetic light and perfect for the Barbies and Kens.”

Another lift with an 18k HMI Fresnel came in handy for more specific backlighting positions and was especially useful for backlighting scenes upstairs in Barbie’s room, where the position of the SoftSun could not always reach the desired spot.

Designing the setting of a scene which sees Barbie meet the doll’s creator Ruth, involved lengthy discussions about what the abstract heaven-like place should look like. As the volume, although an ideal solution, was not available when the scene was scheduled, Gerwig considered asking an artist to help visualise the environment, but then Prieto had a lightbulb moment during a trip to Tate Britain gallery.

“The light and colours of the skies in an exhibition of J.M.W. Turner’s paintings were beautiful and “heavenly”, and Greta loved them too. With Framestore VFX supervisor Glen Pratt and the visual effects team we created an animation that looked like a moving Turneresque sky which was displayed on a Sumolight Sumosky – strips of light you can feed video onto – with magic cloth diffusion material used for backlighting. The actors were lit with three 20×20 frames with Sumolight Sumosky strips through full grid diffusion, reproducing the same abstract animation of colours on their faces.”

Inspired by a scene in Heaven Can Wait (1978), the sequence featured a semi reflective floor which the backdrop lighting reflected onto. Prieto felt the solution was more suitable than the volume for that scene “because the volume is more concrete, it’s an actual video image. This was a softer version coming through a diffusion and was already abstract.”

The filmmakers needed the ability to change the lighting of the cul-de-sac in Barbie Land for different times of the day and one scene transitioning from night to day. A block party sequence had to feel like an exterior shot but with disco lighting, so Walters used Robe BMFL Blades moving lights to create hard spots, and patterns of light on the floor, faces and a disco ball, while the colour and intensity of the main sky light made up of Prolights EclPanels was shifting with the beats of the music.

The approach to lighting in the real world was more like “a traditional movie” although Prieto sometimes brought Barbie Land techniques in. Instead of the Briese light, LA gaffer Manny Tapia suggested using an ARRI S-360 with LA Rag House Octopan for larger scenarios and Nanlux Dyno 1200c with DoPchoice 5’ Octobag for more intimate scenarios.

“But for the most part we used lights we’d usually use in a regular movie such as ARRI SkyPanels of all sizes, HMI Fresnels of various sizes from 18k to 1.8k, Litegear Litemats, and Astera Titan tubes. For example, when Ken goes to the doctors surgery, I wanted it to feel a little cold and fluorescent and embrace the idea it didn’t look as pretty as Barbie Land,” says Prieto.

Real world problems

Following three months prep, shooting ran from 21 March until 21 July 2022, beginning with the Barbie Land scenes captured in the UK. Originally the plan was to shoot everything in the UK before finishing in LA, but COVID meant some sequences needed to be shot in Leavesden at the end.

Although Prieto would have ideally shot the LA sequences in February or March when the light is lower, scheduling didn’t allow this as Gerwig felt it was important for the actors to have lived Barbie Land before visiting the real world.

“At the time of year we shot in Los Angeles, the sun is quite high and unflattering for most of the day. I wanted the real world to feel messy, but I still wanted the light to be flattering, so scheduling was tricky in Venice Beach where Barbie and Ken are roller skating,” says Prieto. “You can’t control the light or follow them with a with a 20 x 20 diffusion, so we shot those early in the morning or afternoon. When we moved to another area in Venice, I could bring in two 30 x 30s with Half Soft Frost diffuser to soften the light but still maintain a feeling of sunlight.”

A moment in the film Gerwig highlighted as significant sees Barbie sit at a bus stop in the real world and tell an elderly woman she is beautiful, to which the woman replies, “I know.” Barbie’s appreciation of the beauty of imperfection was important when determining the look of the real world. “We wanted Barbie Land to always be perfectly lit, backlit and bright,” says Prieto. “When it’s night, it’s not dark and mysterious night, it’s just a little darker and cooler. But the real world was a tricky balance – it had to feel good, but not perfect, which we tried to incorporate into the lighting and photography.”

The Mattel boardroom, although set in reality, was not quite in line with the visual approach for the rest of that world, with set design featuring hints of Barbie Land such as a painted backdrop. The lighting approach was fairly naturalistic, using many flexible and dimmable LED Ribbon strips and ARRI SkyPanel S360s around the windows, which were also used on motors in the cul de sac and beach set to model the light.

Shooting the symmetrical space where the Mattel team chase Barbie around a labyrinth of office cubicles required Greenwood to design squares with LED strips on top of each cubicle. “To add some punch and make the shots dynamic as the characters run around, we brought in moving lights to create a circle of light at the cross sections between the cubicles,” says Prieto. “As Barbie runs, she goes in and out of the hotspot of light as the scene is captured using Steadicam and a rickshaw-like dolly.”

I’m a Barbie girl, in a virtual world

Understanding how to produce proper colour reproduction and skin tones on the virtual stage was a priority for Prieto. “After that it’s simpler because it’s about understanding how you can manipulate the brightness of the volume panels to control contrast of shots, which was pretty amazing. It required a lot of pre lighting to make sure the shots will be successful which was complicated but fun.”

Barbie’s world was brought to life on Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden’s V Stage which Lux Machina helped design, build, and operate using Epic Games’ Unreal Engine. Lux provided virtual production services including engine, systems, and camera tracking for Barbie Land sequences such as car process scenes of Barbie’s convertible and the film’s opening prologue that parodies 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Overseen by Framestore VFX supervisor Glen Pratt, the film features virtual production, previs, postvis and techvis courtesy of the company’s London-based pre-production services team, led by Kaya Jabar and final VFX courtesy of VFX supervisor Francois Dumoulin and his team in Montreal.

“The LED panels that make up a volume stage are basically video screens attached together which make up the lighting environment. But TV screens aren’t made to light faces, they’re made for us to look at, so the spectrum of colour is reduced,” says Prieto. “If you light with tungsten, HMI or ambient daylight and take a reading, the spectrum of light is full. But the light in the volume is full of little spikes and gaps which can affect skin tone.”

Therefore, special LUTs for the volume were essential following testing with dailies colourist Michael Davis. “He was excellent and came up with the idea of using a vectorscope to measure the colour characteristics to see where spikes to the main colours are,” explains Prieto. “So, you photograph, for example, the Macbeth colour chart to see where colours should be and then when you photograph the same colour chart in a volume everything is in different places.”

The volume LUTs Davis, Lucas and Prieto created repositioned the colours to where they would be using the TechnoBarbie or real world LUT, in turn helping skin tone, and facilitating matching scenes shot in regular sound stages and others shot in the volume stage.

When designing the opening sequence – which nods to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey – even the background plates displayed in the volume were the same as those in Kubrick’s film, extended by Pratt’s team to create the dome of the sky and ambient lighting around it. The concept was to put a twist on an iconic moment in film history from 2001 where apes are idolising a monolith and remake it with little girls worshiping the first Barbie doll ever created.

“Going to the desert with a full crew and equipment alone would have been difficult, much less bringing children. By being on a virtual production soundstage, production could control all the variables from the lighting, the temperature, the sound – all the things you would not be able to do if you were shooting out in the desert,” says virtual production producer Kyle Olson.

The sequence was shot by second unit director John Sorapure, working closely with Prieto, and following the idea that as Kubrick was at the cutting-edge of production, if he had made 2001 today, he likely would have used a volume stage.

Backgrounds and characters in that scene were lit by the volume’s LED panels, except moments featuring sunlight which were created using an 18K HMI with full CTL because, as Prieto highlights, hard light cannot be created effectively on the volume.

“Having John on second unit was invaluable, matching the lighting we were using on the first unit and constantly asking questions,” says Prieto. “He’s such an asset and was instrumental in us finishing the movie.”

A small version of the volume was also used for the real-world car chase scene in LA, following a similar technique Prieto used when shooting The Irishman. Large LED video panels were placed all around the car, while plates shot in the same locations as the car chase scenes were displayed on the panels, lighting the characters as if they were actually driving at full speed at the location. Creating the plates also saw the second unit team in LA work closely with stock driving footage company Driving Plates.

George Cottle (Tenet, Interstellar), Los Angeles second unit director, also helped realise Gerwig’s vision for a cliché-packed sequence she wanted to resemble a classic car chase scene. “George has done some incredible stunt work and second unit action sequences, so we relied on him very much,” says Prieto. “We all participated in designing the shots, but he executed the car chase scene better than we imagined.”

In complex shots such as Barbie driving past the airport and greeting a pilot, motion control was used to carry out a fast camera move while the car remained static inside the volume. “The result is the car looks like it is driving past the camera,” says Prieto. “But the lighting from the volume had to match the camera move, which took a lot of prep figuring out the shots through storyboarding and pre vis to create the moving environment, to make the interactive lighting on the car seem as if the camera is simply panning with the car as it drives past us.”

Feminine energy

Barbie brought Prieto together with a new collaborator, DIT Laura Redpath. From the interview, Redpath’s technical knowledge shone through which is important for Prieto who enjoys technology and technique, but admits he is “not an expert in all technical areas. I enjoy coming up with ideas and concepts and working with a team to figure out how to technically achieve them. On this occasion this also included Yvan Lucas and everyone involved in perfecting the workflow.”

Prieto outlined his desire for everyone, from the editors through to Gerwig, to see P3 all the way through as “in some past projects when rec.709 monitors are used throughout the workflow on set, in the edit and visual effects, when the director then moves to P3 in the grade – which is the actual colour space for the DCP deliverable – they expect it to look like rec.709 because they’re used to it.”

While rec.709 looks more saturated than P3 and has a little more contrast, it is more compressed and reproduces fewer colours. As P3 is a bigger colour space, Prieto was insistent they work with it on Barbie. “Laura [Redpath] and the team at De Lane Lea helped me with this, carrying out the necessary research so I knew what we saw in dailies and on the monitors was the same as in the DI, on the monitor Greta had at home and the one I had in my apartment in London.”

Redpath researched and executed an on-set P3 colour and viewing pipeline. “This is something no other show seems to have done before. During our testing period, I first established it was possible to monitor and colour in P3 on my own set-up and then talked to every department it would affect – Dailies, Editorial, VFX, Video, Volume – to see if we could make it work,” says Redpath. “I compiled my findings for production so they could budget for it and get sign off to run the show in P3 from origination.”

As well as stepping in to shoot some additional photography when Prieto was unavailable and directing Pedro Páramo in Mexico, Mandy Walker AM ASC ACS lent a helping hand in the DI. “During the reshoots she was wonderful, we were in constant contact, and she matched things beautifully,” says Prieto. “I was in the middle of Pedro Páramo when it came to the DI, and Greta felt the eyes of a DP were needed. I knew it was in good hands with Mandy as she knew the movie well, having discussed the look with me.”

Much of the look was in place by the grade thanks to the carefully created LUTs and P3 workflow. “Yvan [Lucas] also has a simple yet effective way of grading that’s based on photochemical colour timing based on skin tone. He doesn’t go into the highlights and mid tones of every shot, he works with Printer Lights to make overall colour shifts of red, green, blue and the secondary colours while the contrast and saturation remains the same,” says Prieto.

When Prieto outlined he would like CDL to be done on set using just Printer Lights, Redpath worked with Lucas to establish a precise numerical step value between their system and Pomfort’s Livegrade, so each printer step on set would apply the same values he was used to working with in his final grade. “I created half step shortcuts on my Streamdeck which allowed us to adapt colour with speed and precision,” says Redpath. “Knowing those values also meant a glance at the numbers in Livegrade and I could quickly calculate for him exactly where we sat colour wise.”

As well as the technical and creative achievements of Barbie all the way from pre-production to the grade, Prieto found working on the set a “joyful” experience to remember. “It was fun to be there every day. The people were good to each other and there was a feeling of excitement. So, I incorporated that into the process of my next film, even though the tone of the movie is very different and its super dramatic, dark, and mysterious,” says Prieto.

“I think it really brings out the best in people when you believe in them and let them bring their ideas to the table. Greta taught me that and I felt Barbie really grew because of her leadership, bringing people together and making them feel free to share how they imagine things. Her vision was to not be afraid of trying things. That was exciting, and we all embraced it. There was a real feminine energy on Barbie that I found powerful and beautiful.”