GAME ON

Last year, Rick Joaquim SASC shot his most unusual project to date – Cuttlefish, a live-action video game from Flavourworks complete with over 140 interactive VFX sequences. He delves into the challenges of the choose-your-own-adventure narrative, sharing the tricks and techniques that helped make the visuals shine.

I took on Cuttlefish firstly because I wanted to see if I could rise to the challenge of shooting a project like this. Also, as a cinematographer, you don’t often get the opportunity to say that you’ve done a video game!

We had around three weeks’ prep in May 2022. Because Cuttlefish is a choose-your-own-adventure heist game, it added to the complexity of a typical shoot, so we decided to have a second unit, headed up by Marc Hill ACO. This unit would focus on a lot of the interactive scenes, while we would focus on the narrative scenes.

How it usually worked was we would shoot a scene as you normally would with a master/wide, mids and close-ups, then the second unit would come in a day after us and shoot a close-up interactive element of, for example, a lock being picked or a glass cabinet being sliced open, matching our lighting set ups we would leave set up the day prior. This meant we wouldn’t lose time with our key cast, and we could use hand doubles or stand-in doubles for those interaction scenes.

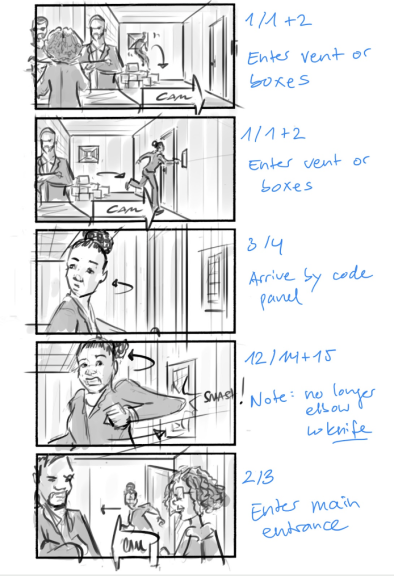

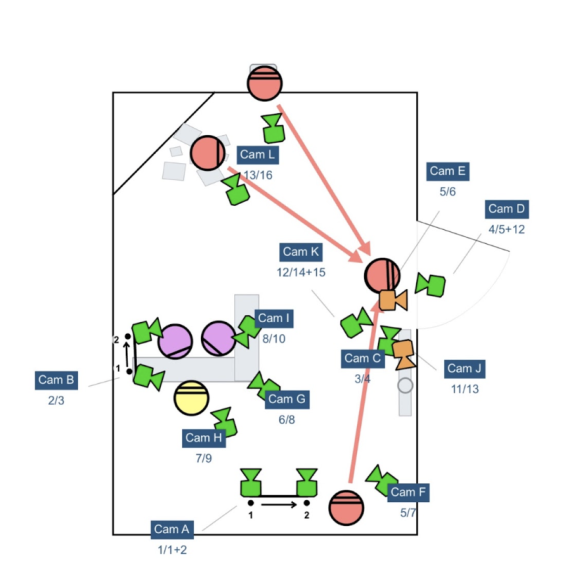

Our director Raphaela Wagner and I storyboarded some of the bigger scenes and then made sure to plan out those with the rest of the team at Flavourworks. We did a lot of diagrams, and blocking was really important. 80% of our locations were set builds, which was great because we could have floating walls and move them out to shoot from at any point.

In terms of the look and mood for the project, we were initially going to go for something a little darker or moodier. But after looking closely at the story and what it alluded to, being a family-orientated game, and keeping in mind that people could be playing this in various lighting environments, it had to look good on a range of devices.

In terms of camera, we shot on the Sony Venice in 6K and had a 10-20% safety aspect ratio which allowed us to crop in, punch in or stabilise shots if we needed to. I wanted lenses that were somewhat sharp, but still gave us a softer vintage feel, so we went for Panavision Panaspeeds, which I absolutely adore – thanks to Panavision London and Victoria Harris for their support.

Because Cuttlefish is a video game, it dictated our camerawork as we wanted the players to feel engaged, and to feel like they’re the ones in the hot seat and making the decisions. A lot of the time I couldn’t do over-the-shoulders because those wouldn’t really feel like our language. Thinking of camera movement, because it was VFX-based, the video game makers asked from the beginning if we could keep it more dolly or slider-based.

I come from a VFX-leaning background which I’ve embraced in my cinematography and really helped me on this project. I did a lot of After Effects work when I was younger, and started shooting a lot of green screen work, so VFX has always come quite naturally. I think it makes you a stronger cinematographer knowing that, for example, if you’re shooting green screen, you can crank the shutter a bit more. I learned to do 90 degrees on the shutter as opposed to 80 degrees, and what that helps you do is get cleaner edges – you don’t get motion blur, or ‘fishfingers’.

I’ll take you through capturing the opening scene, which has our main character Sammy breaking into a gallery to steal a priceless gem and sees her cutting through a piece of glass. This shot was made out of three different plates that could be re-timed while the player controls the circular glass-cutting tool: first, a live action plate of her on chroma green; a foreground interactive plate shot at 90FPS to give the VFX team enough frames in between when a player scrubbed with their fingertips and controlled the elements; and then the actual gem background plate/reflection plate. We would shoot certain elements in an almost stop-motion approach but still at 90FPS. So, someone would puppeteer interactive elements either using sticks, string or operating from behind the chroma green/blue.

Our gaffer, Massimo Fillipi, was a huge help on Cuttlefish and continually helped me shape the lighting. Our biggest challenge was after shooting most of the narrative scenes at 24FPS, we would need to have enough exposure to shoot at 90FPS for certain interactive elements, allowing the game designers or VFX team to take multiple frames out from the footage that would match when the player scrubbed through using their finger on the screen. Some scenes we would light for 90FPS and then just add ND in-camera, but on certain scenes we could afford to bring in more powerful lamps, since these elements were extreme close ups that we could focus lighting into one position or a smaller area.

In all, Cuttlefish was a really fun project and I learned so much. My prep has improved since – I’ve learnt to prep a lot better and faster, which is something I’m really proud of. Along the same lines, my advice to anyone considering a similar project is to make sure you handle your prep time well. I’ve also learned to pull the brakes quicker: if you see something going wrong, then speak up quickly.