EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED

It’s been over 160 years since Charles Dickens published his penultimate novel, but his oeuvre is an endless source of inspiration for contemporary creatives. Cinematographers Dan Atherton and Kate Reid BSC reveal how they crafted the visual language for BBC’s dark new riff on Great Expectations.

Following the rip-roaring success of Peaky Blinders, the crime drama’s multihyphenate creator Steven Knight turns his attention from Birmingham to Dickensian London to give Great Expectations the HETV treatment. This time it’s Olivia Colman who follows in the footsteps of Gillian Anderson and Charlotte Rampling in donning Miss Havisham’s well-worn wedding dress, while Dunkirk’s Fionn Whitehead is rags-to-riches lead Pip.

Giving their oft-told story a fresh injection of creativity fell to cinematographers Dan Atherton (episodes one-four) and Kate Reid BSC (five and six). Atherton’s episodes reunite him with director Brady Hood in a collaboration that first blossomed while studying together at the National Film and Television School eight years ago (Hood, the MA Directing Fiction course; Atherton, MA Cinematography) and has seen their careers grow in parallel, culminating in lensing the Dickensian classic.

“I count myself very lucky – it’s not often that a director breaks into long-form fiction and pushes to have their film school DP,” Atherton smiles as he reflects on the success of his and Hood’s partnership. “I think it’s down to us being very good friends who have similar tastes and outlooks, but what’s really important is that we operate in a space where we can challenge each other. So, the best idea survives – there’s no egos involved.”

What did Atherton make of Knight’s script? “The scripts start out reasonably honest and true to Dickens but get darker as the series progresses. They were really enjoyable to breakdown with the director because they are so visual and varied in tone. Some of the scenes are really funny.”

What most interested the DP was that Knight’s adaptation didn’t focus too much on the love triangle between Biddy, Estella and Pip. “My understanding of this [version] is that it explores mentorship, parenthood and the class system more. Pip and Jaggers. Estella and Miss Havisham. It’s about how the people above you, that you look up to, can be negative influences on your life. You can inherit all their pain and insecurities.”

Although Atherton was well acquainted with the source material, he wanted to avoid any of the (estimated 28 and counting!) screen adaptations so he wouldn’t develop any preconceived notions. “You fall into traps by watching what someone else has done,” he comments. “In this case I thought it was better to have a completely fresh set of eyes on it. But Brady watched a few adaptations – he had to be such an expert on the story.”

In at the deep end

Originally set to shoot block two (episodes three-four), Atherton and Hood found themselves with extra episodes on their hands after the initial block one director, along with DP Benedict Spence, left the project after a few weeks. Naturally, Atherton had read these opening episodes, but he had to step up without any prep and with locations he didn’t know as well. What’s more, these episodes were headed by different actors (young Pip, Tom Sweet, and young Estella, Chloe Lea). “The main challenge was coming on board and not reinventing the wheel but taking what was set up already and developing it further into something closer to our sensibilities,” he explains.

In his early conversations with Hood about the look and mood for the series, Atherton says the director wanted the show to feel “more immediate” than a traditional period drama. “Something rough and ready, with imperfections to make it feel like a reality. With period it’s very easy to approach a scene in a fantastical way. Brady always wanted us to push away from that to find a believable truth.”

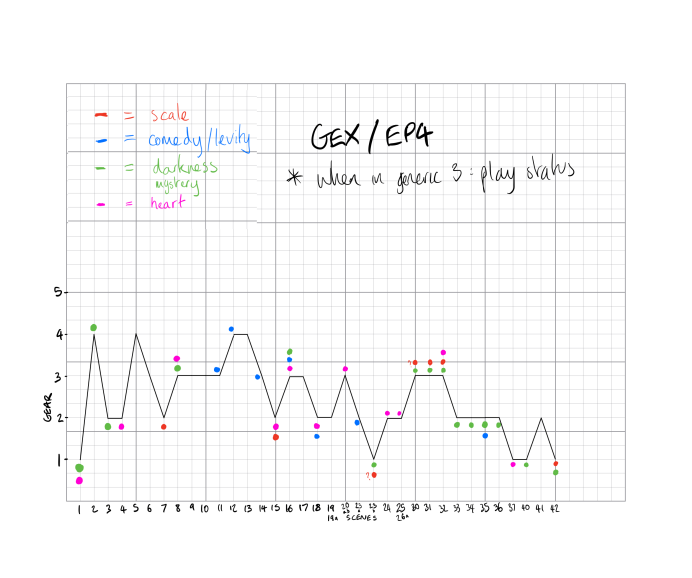

Something that came up in discussions was the idea of a multitonal piece. “What was so entertaining when reading the script was that you had your classic Steven Knight darkness, Peaky Blinders-style scenes, but you also had moments of levity, sarcasm, you had scenes of heart, you had action sequences, you had really complex character scenes,” he continues. “So, the tone shifted between scenes, but it was so smartly written, these shifts didn’t jar. For us it was about how to keep that flow and carefully transition between each of those different themes and tones.”

To ensure these transitions, DP and director spent a lot of time breaking down the narrative together, discussing how best to interpret each scene and its tone – did they want to evoke shock, mystery or levity? They created a way of visualising these tonal changes in graphs to allow them to easily see the episodes’ shifting rhythms and energy.

Swerving period tropes

As prep progressed, Atherton and Hood established that the camera needed to operate more as a narrator and storyteller. For this approach, Atherton drew from Emmanuel Lubezki ASC AMC’s work, especially on Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men. “It’s so honest, immersive, dirty and real,” the cinematographer notes. “In that film I think you really feel the world rather than observe it. One of the reasons for this is that the camera can often pan 180+ degrees and move off characters onto other characters, other parts of the set, and other important aspects of the world.”

What Atherton didn’t like about traditional period work – and what he didn’t think was quite right for Great Expectations – is that the camera work can be quite formulaic. “The cameras often have a very narrow field of view,” he explains. “If you want to see the other side you have to cut to a reverse shot or jump to a wide shot. It can feel like there’s a stage and the camera works in a limited crescent around it. So what we wanted to do was completely abolish that idea and apply more of an 180-degree-plus approach where we put the camera and the audience within the world, rather than as an outsider looking in.” He admits this Chivo-inspired approach had complications from a lighting, VFX and art point of view, but he praises the talented crew for their help facilitating it.

This camerawork was supported by the use of a ZeeGee, which Atherton estimates he used for around 75% of his episodes. Using the ZeeGee makes it a lot easier to develop handheld shot on the fly, he comments – cutting down rehearsal and choreography time for those tricky manoeuvres. The other main benefit of the ZeeGee was how well it worked in tandem with a dolly. “You can attach the ZeeGee with a Garfield mount onto a dolly, and it almost acts as a six-way slider,” says Atherton. “So, you’ve got this operating circle where you can make minor adjustments, all the while reacting to the actors and the background. When you’re on a fixed head it can feel unresponsive, or too linear. What the ZeeGee offers you is this full range of movement, which really enabled us to implement the immediacy in Brady’s approach – reacting to what the actors are doing.”

The ZeeGee contributes to Atherton’s favourite shot of the series, a profile two-shot in episode four of Estella and the irksome Drummle. Here, the ZeeGee is positioned on the dolly with the arm. “It’s a great example of the camera and actors harmonising perfectly,” he notes.

Balancing old and new

Around three-quarters of the series was shot around a 30-mile radius of London, as well as some scenes on location in Shrewsbury and Essex’s marshes. Sets included Pip’s cottage; the ship that burned down in episode one; and Miss Havisham’s entrance hall and ballroom. “All the sets were so beautifully decorated, and had so much texture and dirt to them, they really were a joy to light,” notes Atherton.

There were lots of limiting criteria when choosing the right locations to shoot at – for example, they couldn’t be overly featured in other productions – and often they had some form of historical or natural preservation orders. At the marshes, Atherton recalls the difficulty of filming in the thick mud: “Either myself, the camera or grip team would get stuck in the mud. It was really frustrating but also incredibly funny.”

The older locations were also challenging from a lighting perspective; some places would not allow for rigging to the ceiling, so a lot of the lighting had to be outside. Atherton remembers shooting at Shirburn Castle (which operated as lots of Miss Havisham’s house interiors, while a property in Salisbury played for Satis House’s exteriors) proving especially tricky for him and gaffer Stuart King. “We were on the top floor of this old castle,” he recalls. “We had limited machine access and the location was surrounded by a wide moat. So, we had to build platforms to put lights on and flag all the unwanted sunshine water reflections entering rooms from the surrounding moat.”

Dealing with the classic unpredictability of British weather conditions, from snow and sleet to 35-degree heat, was another hurdle for the production when it came to building mood and atmosphere. Atherton recalls shooting the scene when Pip arrives in London for the first time, which was captured during the hottest day of the year in 2022: “The scene was written as an early winters morning so I needed to dial in lots of blue, surround the actors with negative fill, shoot in backlight and pump the set with plenty of SFX haze. I’m pretty pleased with the results considering how tricky the conditions were. Cast members in full period costume were fainting from the heat – it was crazy.”

Lights, camera, action

Atherton’s camera package, which came from ARRI Rental, included the Alexa Mini LF, which was the perfect size for the ZeeGee. To make sure they were working with as small profile camera as possible, the team ended up stripping the battery from the Alexa and fed it with a long lead to a battery belt, worn by the grip. This allowed Atherton to keep the rig as close to his body as possible, providing maximum range whenever he wanted to track in, out and around the characters.

The Zeiss Supreme Primes were chosen for numerous reasons – principally for Atherton because they’re universal in size, so whenever rebalancing needed to happen, the difference between the 29mm to 85mm was minimal. The DP also rates their speed and their consistent stop – when working with candlelight a lot, this was important. Due to the nature of the project he also needed a VFX-friendly lens: “Not something anamorphic with loads of flares and aberrations – it needed to be clean.” Finally, there was focal length: “The variety of wide angle focal lengths that the Supremes offer really helped us maintain the visual style.”

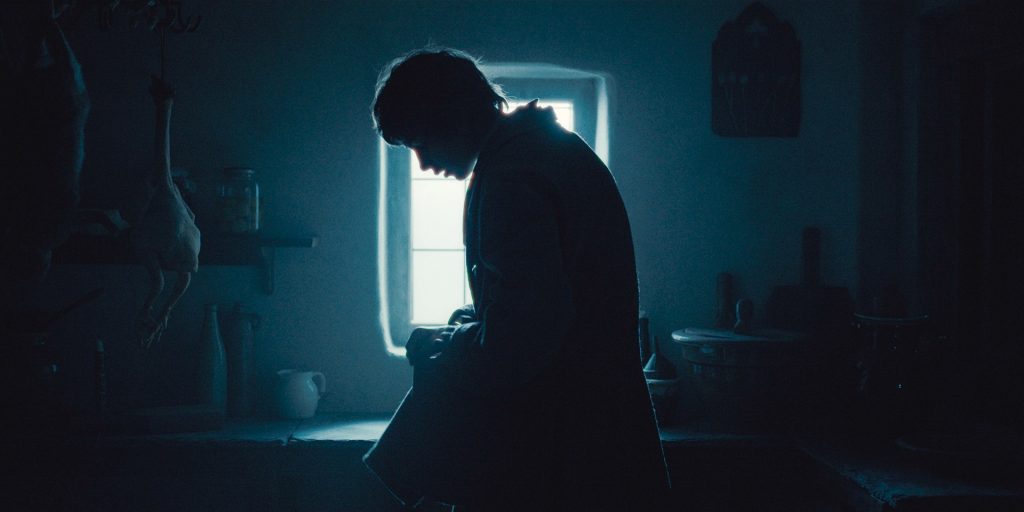

References for lighting included Adam Arkapaw ASC’s lensing, including The King and Macbeth, seeing how he lights a period setting and working with just daylight and firelight as the only light sources. Atherton emphasises how Brady’s vision for the series is rooted in reality rather than fantasy, and he didn’t want too much attention going on the lighting. “The overall lighting aesthetic was to not draw attention to itself too much,” he says. “With period lighting, you can quite easily fall into the trap of hard shafts of light coming through big windows, combined with a garish blue and orange colour contrast you get from mixing daylight and candles. So, what we wanted to do was strip that back a bit and opt for soft pushes, or through windows, and tone down the colour contrast where possible. We’re not really reinventing the wheel here with period lighting – we’re just trying to make it sit it in a more contemporary world.”

Miss Havisham’s scenes were captured at the end of the shoot, meaning that they had a bit more time to do costume, make-up and lighting tests for her. “What’s written in the scripts,” Atherton says, “is that her character has all the windows shut and she sits in darkness and candlelight, which I’d planned to do. However, in the tests I found that actually lighting her character with daylight felt a lot more ghostly than her in candlelight. There was something about a dead white light that harmonised with the nuanced vein work that the make-up department implemented. The daylight also better highlighted the incredible, dirty details of her famously ghostly wedding dress. I loved to throw in a little kicker of firelight at times to catch the reflections of her elaborate head piece and jewellery.”

Atherton ended up presenting the daylight tests to the executives and they all liked it. It felt more right for Olivia Colman’s Miss Havisham and gave her more freedom whilst shooting scenes taunting Pip. “Brady and I really enjoyed constructing these scenes with Olivia. I’m glad I didn’t have to shepherd her towards a candelabra or make her carry a lantern.”

Dickensian disorientation

Kate Reid BSC was approached by director Samira Radsi to shoot her episodes, and loved the idea of bringing Dickensian London to the screen with a talented cast. Like Atherton, a lot of Reid’s episodes took place at night with flame or candlelight as the motivation of the light sources. “Maintaining the intimate handheld style of the series in scenes where the camera is following characters at night on wide lenses and revealing much of the space, often meant these practicals were working hard as sources and certainly leant into the ARRI Alexa Mini LF’s high ISO capability,” she says.

The opening scenes of episode five, which are set in an opium den followed by a pleasure garden, afforded Reid the chance to shoot in a very visceral way and put the audience in Pip’s experience. “I tested a variety of trippy optics at ARRI and settled on a mixture of Lens Baby and a reverse element Zeiss Superspeed to suggest Pip’s disorientated state of mind.” Shooting in the underground caves for the pleasure gardens was the greatest logistical challenge. “It was a hard space for cast and crew to be in for extended periods of time. Plus the caves required judicious use of our oxygen guzzling light sources (the air was carefully monitored for carbon monoxide levels throughout the day) which definitely added a new pressure to the shooting day!” Reid remarks.

Her episodes included several exterior dialogue scenes set at dusk (which couldn’t be filmed over multiple evenings). “I’d achieved this before in environments where I had full control over the in-shot practical’s colour temp and exposure, which in conjunction with riding the iris and camera ISO, works to extend that short ‘blue period’,” she says. “Taking on this challenge with in-vision candle and flame light sources, which can’t be adjusted as the ambient light shifts, was certainly trickier but made possible by careful timing of the shots as dusk fell (when the sky was in shot for example) and the benefit of the precise control over the LED lights now available to supplement sources. Thanks to Toby Tomkins’ delicate work in the grade, I love how these scenes have come together.”

Making the grade

It was key for the production team to give Great Expectations’ different worlds their own distinct visual language. For example, Pip’s home was lit with fire and candles, with the warm light keying faces and filling the room. Meanwhile, in London, the candles are merely highlights for the background while the cold daylight dominates the space and informs the key light on people’s faces. This idea of creating the different worlds and character arcs carried through to the grade, done by Cheat’s Toby Tomkins.

“The execs really wanted to separate the different locations of the story, so we then separated the look into four ‘worlds’,” Tomkins explains. “There was ‘Home/Countryside’ which was used for when we were in Kent where Pip, Joe and Biddy live that hand warmer undertones with a more neutral look that allowed more greens and yellow to come through. ‘London’ which was used for all things London, a slightly harsher look with cool shadows and an overall push to a cyan blue. There was ‘Haversham’ which was used for all things Mrs Haversham, which was smoky with an opium green tint and hazy highlights. There was also a ‘Candlelight’ look that we used for when candlelight was the dominant light source as we needed to tailor the look for such warm sources and make sure the firelight looked real without making the skin tones overly orange or red.”

“Toby is a real talent and has an eye for adding filmic texture,” adds Atherton. “I’m really happy with the end result because at times we weren’t able to quite achieve the gritty aesthetic we were looking for with lighting and atmosphere alone, which is where Toby really came into his element. He was able to take that slight digital edge off and give the dailies the tone we were looking for.”

Great Expectations marked Atherton’s first primary HDR grade. The DP was initially nervous because the initial grade had to be in HDR, with an SDR trim happening later. He knew they’d be opting for a filmic, print look which is traditionally SDR, and what worried him was achieving that look in HDR.

“I didn’t know that we could do that until working with Toby. We were not working in the full 1,000-nit range – and that’s the difference. Instead, we operated with the highlights only 1-2½ stops over the normal SDR range. Having more texture in the highlights allowed us to have smokier mid-tones and softer shadows, whilst still maintaining depth to the image. HDR can be such a trap, because you can stretch out the waveform too far and it feels too big and digital, whilst I feel we got the right balance of having a slightly bigger waveform alongside a very painterly, canvas feel.”

Atherton relished the experience of shooting his first period drama. When asked if he’d do anything differently, he mentions shooting with such talented cast members and remarks: “I’d take a step back and appreciate how lucky I am to be dancing with these incredible actors that were only a few feet in front of me. I only really realised that after I finished the shoot. It was such a privilege.”