Smile for the camera

It’s been the autumn’s unexpected box office hit in all its toothy glory; Smile, originally destined for the streamers, has topped charts on both sides of the Atlantic. Cinematographer Charlie Sarroff takes us behind the scenes on the spooky smash.

You may have spotted them lurking in the crowd at baseball games in Oakland and LA or photobombing the presenters of the Today Show, staring straight at the camera with a sinister grin. Smile’s eye-catching marketing campaign deployed actors to creep out audiences before they even reached cinemas and, boy, did it work: Parker Finn’s directorial debut is enjoying a total worldwide gross of $203 million (as of 6 November).

Adapted from Finn’s short film Laura Hasn’t Slept, Smile follows psychiatrist Dr. Rose Cotter (Sosie Bacon) whose professional and personal lives collide after she witnesses a tragedy at work. Laced with themes of trauma and mental illness, the feature strikes a delicate balance between the horrifying and the heart-breaking.

Charlie Sarroff arrived on Smile, which was shot over 33 days in New Jersey, fresh from lensing another horror, 2020’s Relic. The cinematographer hails from Melbourne, Australia, where he honed his craft at the city’s RMIT University. As a youngster skateboarding was his ‘thing’ and he was inspired by artists such as Harmony Korine and Spike Jonze, whose work spans bridges the gap between skating and film.

His paths crossed with Finn’s quite by chance; at an event in LA back in 2020. Both turned up alone and Sarroff managed to strike up a conversation with the young director. It turned out they’d both be going to South By Southwest – Finn with Laura Hasn’t Slept, the proof of concept for Smile, and Sarroff with Relic.

“Initially, before I was even offered the job, we talked a bit about some references and even some shot ideas he had for the film,” Sarroff recalls. “I think that was a bit of a test for me. There’s a shot at the start of the film where we were bird’s eye over the top of an ambulance, then he wanted that shot to drift up and go through a window into an office and have the scene play out. He told me about it and said, ‘How do you think we should do that?’” The pair would bounce ideas off each other, finding that they had similar approaches to shooting.

Inspirations and references

References Finn gave Sarroff included classic horrors like Rosemary’s Baby, The Shining and The Ring, but one unexpected name that popped up was Todd Haynes. “I love hearing when people want to shoot a genre film like a horror, but they find other inspiration and other directors,” Sarroff explains. “Todd’s done some things that are borderline horror, but what he’s known for are films that are very dramatic and different, so it’s refreshing for me to come to the table with other references that Parker might be on board with.”

Sarroff notes Haynes’ 1995 drama Safe shares similar themes to Smile: “The main protagonist succumbs to illness and becomes very isolated, spending a lot of time on her own. And no-one really believes her at first and she becomes increasingly isolated.”

These details were included in a bible Sarroff created for the camera and electrics department. One of the key camera rules that Sarroff and Finn established early on in prep was that Rose should feel so isolated, that there are no over-the-shoulder shots. “We didn’t want her to be connected to anybody – or anyone in the film to really be connected to one another, for that matter,” he says. “We wanted everyone to be on their own journey, especially Rose, so if you look at all her close-ups there’s no-one. Unless she goes to [her ex-boyfriend] Joe’s apartment and they’re sitting on the couch, but we opened up the aperture so the depth of field was so, so tiny that they still feel isolated.”

Another example of this isolation that Sarroff refers to is at the beginning of the film when Rose hugs her partner, Trevor. “Even [though they’re hugging], we wanted the frame to be quite awkward. It was quite a strange frame and not a composition I’d really go for regularly, but we just wanted things to be a bit off.”

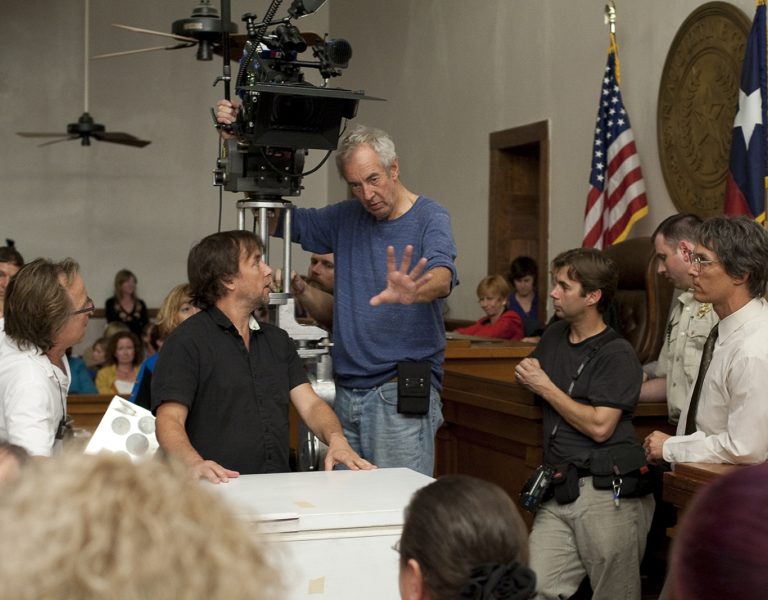

Sarroff and Finn enjoyed a close collaborative relationship (Credit: Courtesy of Paramount)

Sarroff’s bible also focused on aperture and where to sit on the lens for most of the film. “I’m a big fan of using your aperture and lenses as a uniformed way of developing language and then when you change that up, for whatever reason, it has more of an impact,” he explains. “I liked the idea of us only using a few different prime lenses for, say, 90% of the film, but then, when we went to say a zoom or a longer telephoto lens, I feel it has a stronger impact, rather than being on all different lenses for different sizes.

“There were three lenses that we would use for 90% of the film and I’d let the crew know that was part of it and what aperture we’d use for that camera because of the size of the sensor. The depth of field is tiny but that said, we still sat around 2.8 to 5.6, like that range, or like 2.5 to 5.6 and just to keep that kind of uniformed unless we did need to isolate somebody or do something different with it.

“We wanted to be really up-close and personal with Rose, but also have her feel vulnerable in a sense that you want the audience to see a lot of the environment around her, and not know what was maybe able to pop out from somewhere. So we went on very wide lenses in close.”

Those wide lenses were paired with the Alexa 65 for its lack of distortion on wide lenses, hired from ARRI Rental. “The widest lens we had in that lens package was 28mm but that’s actually equivalent to around a 14mm on Super 35,” says the DP. “So, when you were on a 14mm on Super 35, as we all know, things like faces become very warped and distorted when you’re getting close. It’s not very flattering unless you’re shooting a film like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas or something where you want people to look kind of trippy. We didn’t want to do that to poor Sosi [Bacon]. We wanted to keep the perspective quite normal but still be able to be on a really wide lens in close. That’s what that camera is great for. Not only that, it’s great in low light and the resolution is there, if you need to play around with it.”

Sarroff’s fellow Melburnian, David Cole at FotoKem, worked on the grade. Both Finn and Sarroff were set on a filmic look, preferring its characteristics to those of digital images. “It’s not as simple as just laying film grain – we wanted more,” Sarroff remembers. Shooting on film wasn’t possible, so the team sought a colourist with the expertise to recreate the look digitally.

Cole, whose credits include The Batman and Dune, was the perfect fit. “He’s a super intelligent, technical guy but he also has a creative eye,” Sarroff says. They were able to take advantage of Fotokem’s SHIFT AI service, which Cole was experienced with. “You laser scan to film, then you come back and rescan and that takes on some of the characteristics of film,” the DP explains. FotoKem allowed the team perform plenty of tests in different sets of lighting conditions to settle on their perfect look. They was conscious of not making the Alexa 65 look too clean, opting for a textured look and a flattering, slightly out of focus feel with softer skin tones.

Light fantastic

The action in Smile comes to a head in Rose’s old family home, a tumbledown cottage, in scene set at night. Here, Sarroff worked closely with gaffer Joel Minnich to create heightened tension. “The scenes mostly play out there during the nighttime and the set interior was built on a stage, so we had quite a lot of flexibility,” he recalls. “We created some soft ambient moonlight, mainly playing through the windows and to help give the room an underexposed base level of light we would bounce Astera tubes that matched our moonlight HMI/Gel combination into the ceiling. The rest of the scenes lighting is mostly motivated off the old kerosene lantern that Rose uses or the flashlight that Joel brings in. To get more of an exposure in the areas of the frame that we wanted the audience to see, Joel would walk around next to Rose and hold a flickering fire Astera tube in the different areas where Rose aimed the lantern. It was a bit to choreograph but he did a great job.”

It’s here that the work of the film’s practical effects team (Alec Gillis and Tom Woodruff Jr. of Amalgamated Effects) really shines. One of the DP’s favourite things about filming was working with the incredible puppet creatures. “Parker pushes for practicals and wants to do things in-camera, and that’s really exciting as a DP,” says Sarroff. “It’s an exciting moment when you turn up to set and you see these creatures in a tent, and it’s a real treat to be able to actually film something physical.”