THE DARK OF KNIGHT

When shooting Matt Reeves’ The Batman, Greig Fraser ASC ACS drew upon comic book references, ‘70s cinema, combined digital and “emulsified” techniques, and entered LED volumes whilst creating an emotional experience to transport the audience to a Gotham City steeped in crime and corruption.

Cinematographer Greig Fraser ASC ACS says that one of the many things he loves about his job are the “pivots.” He loved them when he shot commercials (something he still does when not busy getting nominated for Oscars, Emmys, BAFTAs, or helping to reboot IPs), when he “could be in a skyscraper, or the next day, in an underground parking lot, doing a two-thousand-dollar music video.”

Now, of course, the pivots go “from a sand dune to the basement of a nightclub.” And they’re not even on the same planet! The sand, of course, refers to his multi-nominated work with director Denis Villeneuve, in adapting the science-fiction classic Dune, set on the distant world of Arrakis, with its also distant messianic, “spice”-infused timeline.

The basement, however, is back here on Earth, or at least a mythical part of it, being a Gotham City nightclub run by John Turturro’s crime lord, Carmine Falcone, with an assist from a nearly unrecognisable Colin Farrell as The Penguin. All of them, of course, relentlessly pursued by Robert Pattinson’s young Bruce Wayne, and his storied, titular alter ego, The Batman.

But the pivot isn’t just one from one well-loved fictional universe to another, but also in moving from references like the sun-blasted yet starkly revealing work of Freddy Young OBE BSC in Lawrence of Arabia, to the also starkly revealing shadows in ‘70s neo-noirs by masters like Gordon Willis ASC and Owen Roizman ASC. Indeed, Fraser notes that many of that decade’s highlights – Chinatown, Godfather, non-noir fare like Nashville, Cuckoo’s Nest – were “constantly discussed,” particularly for “the feeling you had sitting in the cinema” – the transporting, and perhaps unsettling encounter – which director Matt Reeves was looking to replicate in his own visit to Gotham.

As was Fraser. “I remember the feeling I had watching those (films). Constantly as filmmakers we’re striving to create an emotional experience in our audience.”

Though most of those references, he adds, were for “tonal references, for the emotional” aspects of the story, adding that even in a close aesthetic cousin like Chinatown, “there wasn’t a guy dressed in a leather suit with ears.”

Besides the adapted neo-noir feel, there was another thing Fraser shared with the likes of Roizman and company: use of film to create even more subtle tones, moods, and shadows. But he also had something unimaginable in the ‘60s and ‘70s: a series of bespoke lenses to use on a digital camera.

“It was quite clear,” he says, of the pre-production work and discussions with Reeves, that “we were going to shoot digital. The shots needed to be pretty precise – digital was the best tool to allow us to see what we were getting at the time.”

That precision was captured with ARRI Alexa LF, with camera, lenses, and grip provided by ARRI Rental UK. The glass used was newly built by them: “ALFA lenses – Arri Large Format Anamorphic.” One batch, which Fraser reckons was Series Three, was sent to Germany for the upcoming Netflix horror mystery series 1899.

The Batman used Series Two, which he describes as “a little more extreme. The good thing about these ALFAs, we dialed the centre of the image to be sharper than normal (and) had the resolution to be able to go through the process of negative to print. We had the softness we also wanted,” yet with “resolution clear in the centre.”

He describes that look, that sharpness, as “very indicative of Batman as a character, and Bruce Wayne as a character,” someone, whether the cowl is on or not, always scrutinising his surroundings.

And if one scrutinised that previous quote wondering if “negative to print” also inferred actual film stock used in the process, one would be right. Fraser describes the dark tones they achieved as a “combination” of digital and what we might call “emulsified” technique. “When we were filmmakers with film,” he recalls, “we had a whole series of options,” listing basic items like varying film stocks, filters, the ability to “flash” film, and more.

Then, in that early 21st century transition to digital, “what we got in return was a digital sensor that was technically fantastic,” leaving you something “technically superior to film,” but “we lost the ability to be able to manipulate and swerve and finesse the image, the way that filmmakers on film are able to do.” But of course, he allows, there were also always those moments of existential suspense until you could see each day’s work, along with “hoping the lab hasn’t blown up.”

Enter, then, collaborators such as David Cole from post-production vendor Fotokem and DIT Dan Carling, willing to match the vision of Fraser and Reeves.

Fraser describes the process as shooting, editing, and then “you do post, you do your DI and grade your movie” or at least part of it, because then “you film out to negative, then you print that negative, and scan it back in.”

You have, in a sense, introduced “that emulsion, but in a more controlled way. This has an analogue quality to it.” He also reports having been “blown away,” when first projecting the scanned DI.

But earlier chiaroscuro films weren’t the only place he drew tonal inspiration from, as he also went back to the very medium that gave us Batman to begin with: “the comic books. I looked personally to them. When you look at a comic book image – you might have six images on a page,” adding that “every frame is drawn so that there’s clarity to (it). “And he adds, so that your eye is drawn to where the artist wants it to be.

And in terms of Batman’s silhouette, he acknowledges dealing with “a very iconic shape,” so he found it helpful to see how that shape lived not only on the screen, but on the page, and what sorts of techniques made some panels more moving than others. “Without an emotional connection to the characters,” he continues, “we end up with something that’s just fodder.”

Additionally, Fraser “feel(s) like comic books are as important a source of inspiration as plays, as Shakespeare, as films – part of the collective consciousness. Trying to combine those mediums into a moving image, was the main goal that we had.”

And those images really did move quickly, sometimes as settings shifted from the UK to Chicago, particularly Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden, in the case of the former, using five of their stages, and a backlot where a large part of Gotham was created. In fact, “there were scenes that linked directly,” from that backlot to locations in the Windy City, all within a single beat of action. Fraser would match “colour temperature readings – I was quite meticulous about being spot on.” This was another place where the interstitial use of film was helpful, acting “a little bit like a gap filler (for) a few deficiencies in the background. It can help spill over.”

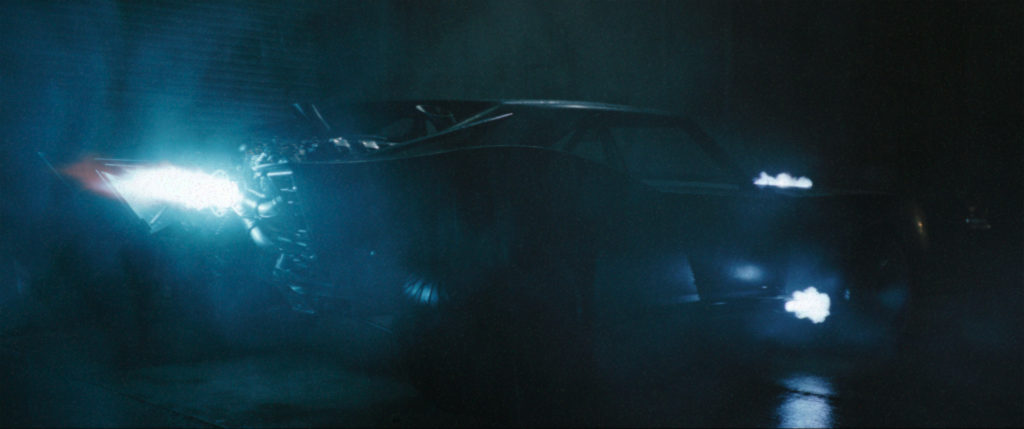

Another test of moving from locale to locale – at breakneck speed, in terms of story – came during the main chase scene, between The Penguin, fleeing a drug shipment gone bad, and a pursuing Batmobile, as the famed member of Batman’s “rogues’ gallery” tries to elude his pursuer with a lot of deliberate, high-speed wrong way driving, leaving rolling, crashing exploding vehicles in his wake.

“That was where it started to get really interesting,” Fraser says, “Instead of using our production lenses, we changed (them) – and had production buy some old ARRI (Alexa) cameras and strap them to old trucks and cars.”

Affixed to the Arris was ”rehoused old glass,” from Ironglass, who also created lenses for them, though this time, rehabilitated ones, along with some Atlas lenses, too. “It was a real mixture,” to complement the mix of locales in London where the chase was filmed.

And they approached the filming for that sequence “very differently. We had a set of clear filters; silicon drops to imitate water spray. We tried to make sure there was always mess, always dirt” visible.

Much like Gotham itself.

He also says that some previs and an early look at 3D set modelling helped plan the chase as well.

But to emphasise the city’s decidedly unplanned, and constantly fraying look, they also tried “to use the real lights, like fluorescent lights,” whenever possible. This even lead to a trip to Chinatown – not the one from the titular film – where he and gaffer Jamie Mills, with the idea that they would swap their newer tubes from the set with older ones from the restaurants they’d visit, inveighing against “the general wisdom (that) you make all the fluorescents the same colour,” when he points out the reality is those tubes get replaced at different times, over the years, leaving a kind of geologic layering of colour tones.

While the swap didn’t happen – Fraser opines that the field trip was more “an excuse for me and Jamie to have a night out” – and a lot of more modern gear, like Digital Sputniks and Hudson Spiders were used, he never wanted the lights to feel digital, and used real sources when he could.

Extended possibilities

Virtual production techniques and LED innovation also came into play when creating Gotham’s dark underworld. In the lead up to shooting The Mandalorian – which used an LED volume to produce immersive environments that responded to camera movement and rendered in real time – Fraser shared details of the pioneering technology and production practices being used with Reeves.

“When Matt got the job directing The Batman, I told him what I was doing on The Mandalorian and that we were looking at this technology that would allow us to stage scenes at sunset, early morning, nighttime. This really piqued his interest.”

Excited at the prospect of the control that shooting in a volume could offer, Reeves recognised the benefits of working with LED screens when capturing The Batman’s lengthier sequences that “required consistent light over a long period to get the best out of the performance”, including those taking place on a construction site, at a cemetery, and on a rooftop.

With director and DP in agreement about what they envisaged virtual production could offer, LED specialist VSS Ltd explored a variety of screen configurations capable of fulfilling the filmmakers’ ambitions. In 2019, the team began working with Fraser and Industrial Light and Magic to design a bespoke 600 sq metre LED volume at Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden which satisfied all requirements and accommodated a number of sets with quick turnarounds.

Multiple camera tests and LED shoot outs saw the AOTO 1.5mm panel selected for its high resolution, viewing angles, and uniformity. VSS technical director Jonny Hunt then created unique solutions to allow screens to separate and move, and that could accommodate rain-rigs, camera moves from outside the volume, and stunt work. Alongside the in-camera AOTO panel, ROE 3mm and 5mm products were used for additional lighting sources, with VSS also supplying screens for vehicle process work and multiple other LED set-ups.

One of the highlights of embarking on this journey of investigation and adaption, says Fraser, was “getting the chance to try out different volume designs that I suspect are superior to many of those that are out there right now”.

As for what Fraser will be taking from his time in Gotham back to the sands of Dune, when he shoots the upcoming sequel, he declares that he’s “absolutely agnostic – I don’t know if there’s a word that runs beyond agnostic,” particularly when it comes to cameras and lenses, saying that “while I’ve loved the cameras I’ve used in the past,” he also likes using equipment that “runs me outside of my comfort zone.”

But he also allows that while “It’s unlikely Arrakis will look like Gotham, maybe there are crossovers, or lessons learned, or things I want to try.”

As for adapting to “lessons learned,” it seems likely that both the constantly scrutinising Paul Muad’Dib, and The Batman would approve.