Glass Act

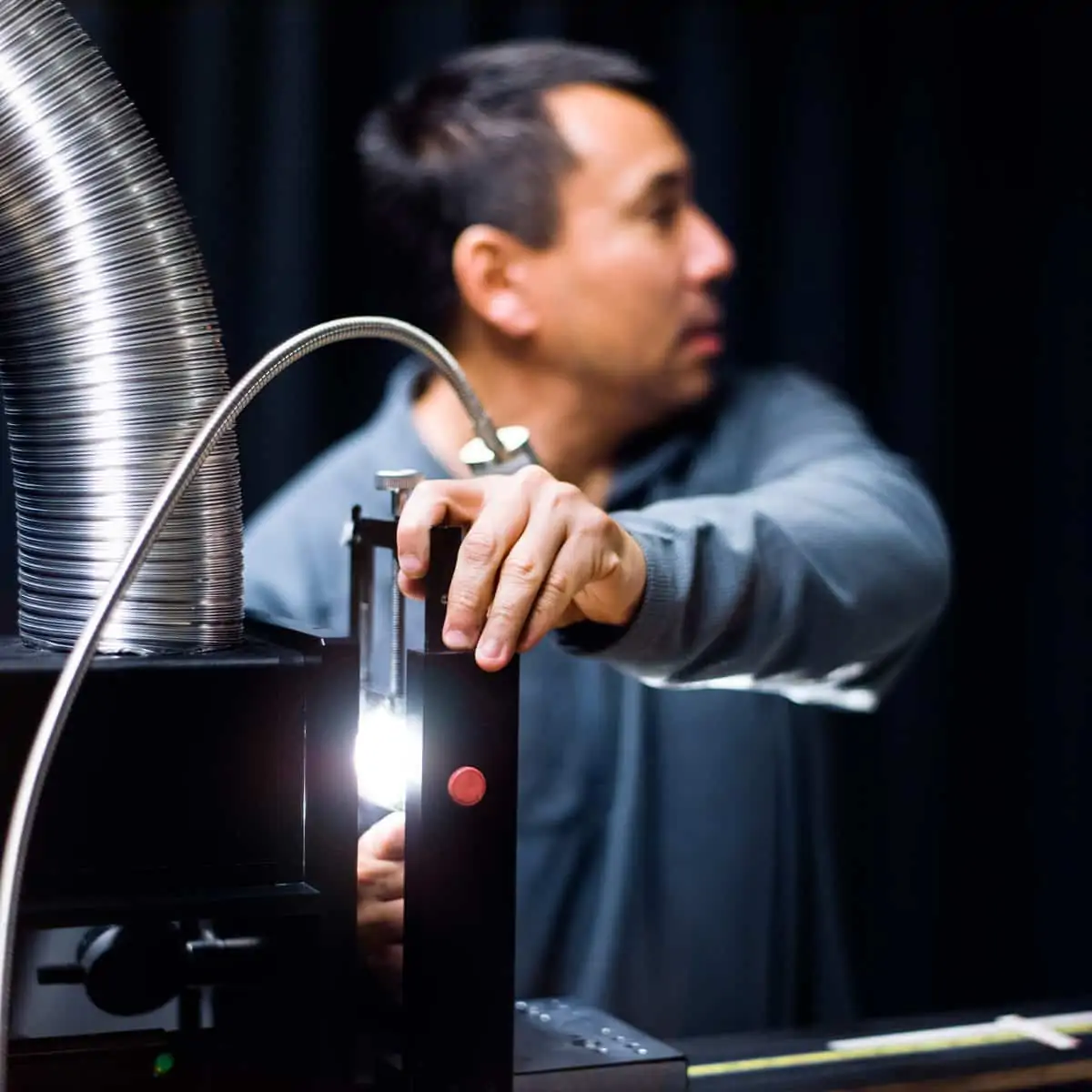

Innovator / Dan Sasaki

Glass Act

Innovator / Dan Sasaki

BY: Adrian Pennington

Revered by cinematographers as a magician capable of conjuring quintessentially distinctive looks, Dan Sasaki, VP of optical engineering at Panavision, modestly dismisses his lauded status.

“I am definitely no Leonardo da Vinci,” he says. “I'm a person who knows how to deconstruct something and how to learn from others. When I've made mistakes cinematographers have let me know it. I'll bring something that I think answers all of their problems and they'll say, 'Why have you brought me this? It's unusable' or they'll push me much further into developing something with a far greater emphasis than I'd imagined.”

The truth is that, despite his humility, Sasaki embodies the Panavision brand in his dedication to artistic perfection. His successes have included the flare lenses used by Janusz Kaminski ASC on Saving Private Ryan (1998); the specialised 20mm Anamorphic that John Schwartzman ASC used on Pearl Harbour (2001); the design of the Anamorphic Wide-angle Zoom (AWZ), which has become known as the 'Bailey' lens, after cinematographer John Bailey ASC; and the refurbishing of vintage Ultra Panavisions for Robert Richardson ASC to shoot The Hateful Eight (2015).

“Designing a lens is an art form because you're helping artists to express themselves,” he says. “It doesn't come about by some mathematical formula, but by adding or subtracting detail to produce the image that a cinematographer desires. It's a very analogue, human process.”

Of his three decade-long Panavision career, Sasaki says, “I didn't have a choice. My father had worked at the company since I was a year old, and at the dinner table growing up it was always a fascinating time to hear him talk about his day, analyse the movies and explain the technical intricacies of the cameras.”

Sasaki recalls being invited to an advance cast and crew screening of Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977, DP Vilmos Zsigmond ASC HSC) and his father Ralph talking about working on the cameras and lenses for films like Fiddler On The Roof (1971, DP Oswald Morris BSC) and Jaws (1971, DP Bill Butler ASC) in the 1970s.

Although Sasaki senior, who retired as VP of operations in 2008, invited his teenage son to join him during school vacations in the Tarzana headquarters’ workshop, this was more because Sasaki junior showed a passion for mechanics rather than about any plan of succession.

“I had an innate curiosity about how things worked and was constantly taking things apart, like TVs and radios,” says Sasaki. “I used to watch Dad put cameras together and think that this was cool, but it didn't really cross my mind to make working with cameras my career.”

In fact, nothing really prepared him for work at Panavision, not even the physics he studied at Long Beach State. “My training really started when I got there,” he says.

He joined the optical department of the company aged nineteen in 1986, and spent the next four years in the servicing division repairing glass - dusting lenses, cleaning, engraving and checking inventory.

“Dad was very protective of Panavision's reputation – he wasn't going to let just anyone get involved,” he says. “Also, he didn't want to show any favouritism, least of all to me, so I believe he held me down for longer than he would have with other people until he felt I knew what I was doing and that I'd matured enough to move up the ladder.”

Sasaki became lead repair operative then manager of the section, gaining more responsibility and experience over time. It was a formative period bringing him into contact with cinematographers and assistants. Some of the cinematographers that helped a lot in the early years were Wally Pfister ASC, Samuel Bayer, John Alonzo ASC, and John Schwartzman ASC. Some assistants that helped were Richard Mosier, Alan Blauvelt, Dick Meinardus and Norman Parker.

“I vividly remember the first feature I worked on which was Dances With Wolves (1990) with Dean Semler ACS ASC and camera assistant Lee Blasingame. I think it was then that Dad realised that maybe I'm not too dangerous to be let loose, that I wasn't going to upset the apple cart.”

"I had an innate curiosity about how things worked and was constantly taking things apart, like TVs and radios. I used to watch Dad put cameras together, but it didn't really cross my mind to make working with cameras my career."

- Dan Sasaki

Sasaki was mentored by Tak Miyagishima, Panavision's fabled lead mechanical designer from 1955-2011. “He told me never to give up. He said, 'treat every challenge as a learning process' and he taught me how to get the best out of working with cinematographers and not to be afraid of bringing a different perspective to the table. He impressed upon me that being different is part of the innovation process.”

Sasaki credits his first break as creating the first C60mm Anamorphic lens for László Kovács ASC on Multiplicity (1996). “László thought there was too big of a focal length span between the 50mm and 75mm. His thoughts were that a 60mm would be an ideal focal length to bridge this gap and it would closely correlate to a 27mm lens in the Super 35 format. As a result, this became such a popular focal length and the 60mm became a standard focal length in our future builds.”

Sasaki used The Hunt For Red October (1990) for Jan De Bont ASC, as a platform to optimise the classic C-series line of anamorphic lenses. The process included updating the optics and determining ways to flatten the images on the film plane. This paved a path for the C-series lenses in use today.

“It took me a while to figure out a signature look and I'm quite sure that someone else will have another way of customising lenses which will do the job just as well. If I have achieved anything it all stems from the cinematographers and camera assistants, Tak and my Dad who inspired me.”

The look of a show is an alchemic mix of elements from the optical density of the photographic emulsion to the shooting style and visual effects. “It is never as simple or as binary as removing the coating from a lens,” says Sasaki.

When Kaminski sought Panavision's help for Saving Private Ryan, Sasaki figured that being a WWII film a gritty old lens would fit the bill. “When we did initial tests Janusz felt it looked too modern, so we removed the coating,” he says. “That only served to add another layer of error into the lenses – which gave them an aberrant quality, something pre-1940, but it offered a flare that they wanted. That process of trial and luck worked perfectly for that film but only when combined with other elements like the shaky camera movement and the timing in post.”

Now, instead of removing the coating from lenses Panavision has found a way to produce the same look without having to destroy the lens and achieve better control over the degree of effect and unwanted glare.

“Many cinematographers come in asking for a look that’s in their head and it’s our job to try to interpret that,” he says. “Other times we’ll offer them some choices and suggestions. For example, on Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) Dan Mindel BSC ASC said he wanted it to have a 1970s kind of aesthetic. We researched what a lens from the period might have looked like with modern film stocks and started to build something that we felt would maintain that aesthetic without the liabilities associated with an older lens.”

Surprisingly, Sasaki says he doesn't own a camera. “I'm no artist or photographer so my impression of what a cinematographer wants may not be quite right. Sometimes they will send me a still photo or example of what they would like to see. Based on the example or description we can start determining methods to customise a lens. It usually takes a couple of iterations before we match the cinematographer’s expectations.”

The vogue for degrading of lenses – decoating, recoating, antiquing – is exemplified by the exacting demands of Robert Richardson and director Quentin Tarantino in their search for a distinctive look to match the wide screen wild west of The Hateful Eight.

“Bob and Quentin wanted to shoot 5-perf 70mm film but the only choices were old System 65s used on Far And Away (1992, DP Mikael Salomon). We tested these for them but they suggested that the image looked round and predictable. Bob challenged me to find a look that hadn't been seen before. Bob always knows what he wants and he knew that if he kept talking my ego would get the better of me. So we looked in the archive for Ultra Panavision lenses which hadn't had light through them since Khartoum (1966, DP Edward Scaife BSC). On most the grease had atrophied so the lens couldn't move or the glass was fogged up, but one lens was in working order. We threw that onto the test projector and before I knew it Bob declared that they will shoot the picture with that style of lens.”

Sasaki worked with Richardson's first assistant Gregor Tavenner to retrofit 15 lenses to work on a reflex camera. This included converting them for follow focus, increasing the working depth, and varying focal lengths (some that didn't exist in the 1960s) in just a few months.

The digital revolution has introduced a wave of super sensors making large format much more accessible. Sasaki feels that artistically, large format offers many depth perception cues that are very attractive to the human visual processing system. “Large format offers many features that both cinematographers and directors can identify with immediately, including increased magnification, perspective and character,” he says. “We’ve seen recent films that span from Super 16mm all the way up to IMAX. Cinematographers are no longer bound by old standards in formats or capture media. Ultimately, though, whether 65mm, 35mm, 16mm, Anamorphic or spherical, the cinematographer will choose the best format to fit the story. They now have more choices than ever.”

Dan continues to mine Panavision's library of vintage optics. In some cases, lenses are built from the ground up and some are mechanical updates to the originals.

Richardson turned to Sasaki again for Live By Night (2017), directed by Ben Affleck, combining the ARRI 65 with the newer Sphero 65 series, also used by Jess Hall BSC on Ghost In The Shell (2017). The Primo 70 series were used by Rodrigo Prieto AMC ASC on Passengers (2016) and System 65 lenses by both Ben Davis BSC on Doctor Strange (2016) and Adam Arkapaw ASC on Assassin’s Creed (2016).

“These three series of lenses have intrinsically different imaging characteristics. The one thing that is becoming essential in this format is the request for T2.0 or faster optics. In nearly every case we had to create optics from scratch to achieve lenses with such large imaging diagonals and high speed.”

Another example is the re-optimization of the Ultra Panavision 70 anamorphic lenses used by Greig Fraser on Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016). “We started with the base 1.25x anamorphic squeeze lenses used on The Hateful Eight and made many modifications to suit Greig's needs and accommodate the Alexa 65 camera. In many cases, we had to completely start over with the base lens and rebuild it to become a more modern version that met his expectations.

He is currently working with Hoyte Van Hoytema ASC and director Christopher Nolan on Dunkirk (2017), at least 60 per cent of which is being shot in native IMAX and for which Sasaki has built optics to fit airplane cockpits. He also recently developed anamorphic lenses for Steven Spielberg's Ready Player One (2018, DP Jansuz Kaminski).

Has he ever not managed to solve a problem? “There are times when I try to violate the laws of physics. I sometimes try to violate the Lagrange Invariant [a conservation of energy law] by trying to get more light through a system than it will allow. We have to try.”