No Fear

Anthony Dod Mantle DFF BSC / 127 HOURS, The Eagle & Dredd 3D

No Fear

Anthony Dod Mantle DFF BSC / 127 HOURS, The Eagle & Dredd 3D

BY: Ron Prince

With his bulldog, ‘Eddie-Monster’, curled up at his feet, and his family retiring to bed, Anthony Dod Mantle DFF BSC spoke to Ron Prince via Skype, about his work on 127 Hours, The Eagle and Dredd 3D. The cinematographer had just come back from collecting a prestigious Award in Marburg, Germany, so we kicked of with that…

Q: What were you doing in Marburg?

ADM: They presented me with the 2011 Camera Award, and a cheque the size of a surfboard, physically speaking. It’s a noble event and humbling to get this award, with previous winners like Raoul Coutard, Jost Vocano and Robbie Muller. They screened every single film I’ve ever done in Marburg from about December onwards – Dogville, 28 Days Later, Antichrist, Slumdog, the whole lot – and people had written dissertations about the films and my work. They knew me. Marburg is a university town, with intellectuals, professors, writers, journalists, students, theatre people. There were classes around the clock for three days where I discussed my work in detail on stage. People have stored up questions and theories, and you find yourself embedded in discussing work that sometimes can be difficult to revisit after so long. It was exhasuting, but a great honour.

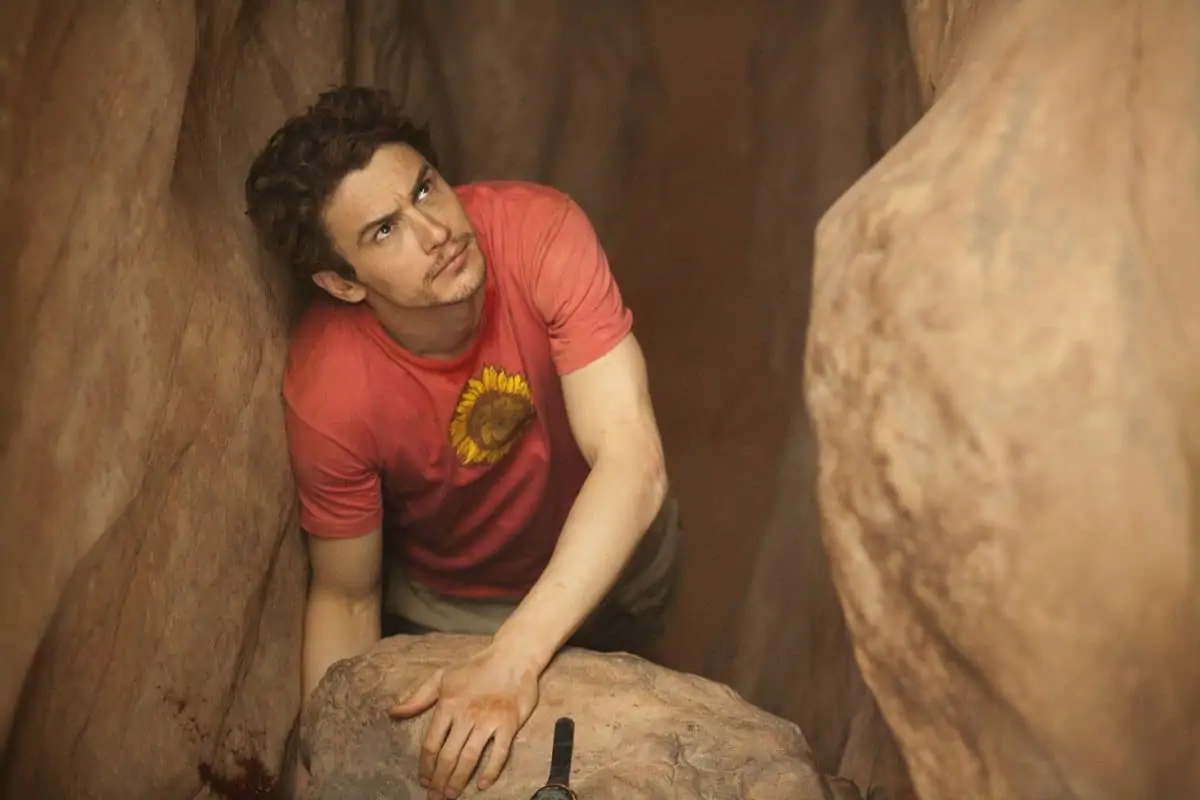

Q: Tell us about your work on 127 Hours?

ADM: It’s a little bit of chemistry between digital and celluloid. There was no doubt, we would have to use digtal. The malicously-tight physics of the canyon defined our approach. Danny (Boyle) was insistent on portraying a feeling of imprisonment, and there was no way I, nor Enrique (Chediak), could film with a camera on our shoulders. So I worked with HD Rentals out of Los Angeles to strip the bodies off some SI2Ks and came up with three different cameras – a Fist Cam with C-mount lenses, that could get intimately close to James Franco’s face, mouth and neck, plus two gyro-based handheld cameras, with PL mounts for Zeiss and Cooke lenses. HD Rentals supplied the gear and rebuilt the equipment to the extent that they could to meet my needs, but I brought in my loyal colleague and HD camera supervisor Stefan Cuipek to finalise and organise the last details. Without Stefan we would have been in trouble. There was so much last-minute prep, with location logistics and other recces, that we had precious little time. Added to this we were developing a workflow that could support the turn around of two camera crews shooting parallel, one with me and one with Enrique.

There were several video elements to the story too, as the real life Aron left video messages about his predicament – a visual epitaph – using a digital consumer camera, which we matched pretty closely. I also used several Canon 1D, 5D and 7D DSLRs to shoot generic material where I felt it worked. We shot timelapses, and other relevant images about his route into the canyon that are revisited during the film in the form of a DSLR still-image burst montage executed wonderfully by our VFX supervisor Adam from the Union VFX company.

We also built a bridge and a contrast between these scenes and the rest of the film, especially the landcapes which we shot on film with rebuilt Moviecam Compacts from Denny Clairmont in Los Angeles. We shot on mixed daylight and tungsten Kodak stocks, underexposing sometimes for mood and grain.

Q: What creative references did you use for The Eagle?

ADM: As a rule I normally look at photographs, paintings and drawings. Rarely at other films. For me it’s about images that invoke a mood. The Eagle has lots of mud, blood, nature and textures. Lots of hardship too. Kevin Macdonald (director) and I looked at Arcimboldo’s paintings for organic textures, and talked about Tarkovsky’s use of desatured, gentle hues of the colours in nature. In search of inspiration and insight for the harsh conditions the Scottish Seal people lived in, we looked at WW2 concentration camp art and graphic images made by anonymous Polish artists portraying the dead. I also pulled out shots from my computer – macro stills of nature on Antichrist, some lens baby images I shot on Wallander, images with weird halations from Brothers Of The Head when I shot the neg back to front. I also found a cross-processed shot from Millions that Nigel Walters and Daf Hobson helped me to shoot.

Q: How long did you have to shoot The Eagle?

ADM: We lined up for about five weeks, and shot for eight weeks in Budapest and then went immediately to film in Scotland for four weeks.

Q: You had to shoot in Hungary and Scotland, so how did you prepare?

ADM: It was always going to be shot on celluloid, well apart from the odd dribble of naughty Canon 5D stuff, that I can’t help doing. As a film that take places north and south of Hardian’s Wall, I went on long recce’s with Kevin to see how we could best bring together the dust and summer sun of Budapest, with the crazy climate of the west coast of Scotland. In Budapest, I wanted especially to see the areas where they were building the forts, as I knew I had to work out every single camera angle to disguise the trees and vegatation utilising, in worst cases, side lighting, and whenever possible, shooting against the light. This was the only way upfront that I could kickstart the desaturation, subdue the colours, so they would match the Scotland shoot. I also spoke to designer Michael Carlin very early on about the height of the walls, not just for shooting 360 degrees, but about the positioning the lighting on set. It’s an historical story, with only fire or candlelight, so it was all about how to get naturalistic lighting, reflecting off the walls and the floor, through windows. I knew that a great deal of top lighting would be necessary on some of the sets. I did plenty of testing with filmstocks using lots of filters, and worked very closely with Adam Glasman the DI colourist at Ascent 142 (now Deluxe 142). I come up with colour palattes on films, which I mark on the slate. The Eagle had eight or nine looks. Before the shoot, I calibrated my computer as closely as possible to the ones in the DI suite, to make sure we were on the same page.

Q: I heard you did some unusual things with exposures?

ADM: I had to combat the electric brilliance of modern day stocks, to give the film an historic feel. During tests I underexposed, pull-processed and push-processed, did technical bypasses and cross-processes, and then went to Adam in the DI suite to see what I could also achieve there. We really knocked the negative around with diffusion, and even got an ARRI Relativity noise reducer in. On the shoot I push-processed every single stock, Fuji and Kodak, between one or two stops – the 500 ASA went close to 2000 ASA, and the slower 250 ASA I pushed to 800 or 1000 ASA. Along with Adam, I have to thank Darren Rae and his team for their consistent support.

Q: Tell us about your camera and lighting packages?

ADM: Thomas Neivelt, my gaffer, and I worked with Russell Allen at ARRI in London on the cameras and lenses. We had several ARRICAM LTs and ARRICAM Studios. They found some old Cooke Panchos and new Cooke S4s, and supplied cranes and tracks, good old fashoned stuff. I used a lot of filtration, especially my own filters. We had a mixture of tungstens and HMIs that we got from ARRI’s rental partner Vision Team in Hungary.

Q: How do you work with Thomas your gaffer?

He worked with me on The Last King Of Scotland, Brothers Of The Head, and all of the films I’ve shot with Danny Boyle. It’s a great advantage to have someone who knows me as a person, my tastes, and can deal with the rental houses whilst I am tied up in other matters.

"I am fascinated by technology, and feel we should be allowed and encouraged use new technologies – so long as you can argue the logic behind using them. It’s about honesty, being open-hearted, open-minded."

- Anthony Dod Mantle DFF BSC

Q: How did you go about creating the dream/nightmare sequences?

ADM: They were a bit like the cerebral journeys in 127 Hours. There were nightmares and flashbacks, and you have to separete these for the audience. I shot the nightmares using combinations layers of glass, filters, rags, flares, strange shutter dragging – lots of things to degrade the image. For the flashbacks I used high contrast filters glued to lens babies, and torches shining into the lens. I also used the DI to take the looks a lot further, twisting the overall colour palattes of each, with yellow being a predominant colour for the flashbacks.

Q: Were there any surprises while you were shooting?

ADM: Even though I knew Scotland was a tough call, weatherwise it was cold, dark, and the rain was punishing and incessant. You could see it visibly stinging the actors’ faces. It haemorrages moisture, no wonder there are so many golf courses. The light moves all the time too, which made exposures very tricky. We were shooting in some pretty inaccessible places on the west coast, and there was a lot of lugging to do. What with climbing around canyons on 127 Hours and the rigours of Scotland these films got me fit, as well as nearly killing my camera team. It is always a pleasure to see Alistair Rae come out with his steadicam, but when he appeared wearing football boots, you knew it was going to be a muddy day.

Q: What are you thoughts about the DI process?

ADM: I adore the DI. It’s a very creative part of filmmaking, with so much potential. But a DI must only be possible with the DP, no matter how brilliant the grader, and I like to contract myself into the grade whenever possible. A director may have been living with their project for months in an edit, whilst the DP has been off shooting elsewhere. In the DI everything comes together, the images, the audio and music, and the DP comes with fresh eyes. The director, producer, designer, costume designer, art department, all get the chance to see the film properly, far more than in the online. I’ve got amazing tools at my disposal, not just for colour, but to adjust the textures, the balance, the framing, so I can make the story tighter and better right to the very end. It’s an unbelievebaly creative place to be.

Q: What can you tell us about Dredd?

ADM: Kevin’s brother, producer Andrew MacDonald, approached me a while ago. It’s written by Alex Garland, a very astute, creative writer, who I’ve known since 28 Days Later. It was shot in South Africa on 3D – around 13 weeks principal, and seven weeks 2nd unit photography. It’s a dangerous film, in the sense that the story places itself precariously on the floorboards of an action sci-fi genre film whilst underneath there’s a no less entertaining allegorical comment about this kind of cinema and the violence that tends to come with this kind of product. Visually we have gone at it hammer and tongues. We shot entirely digitally, in scope, using RED MX cameras and SI2Ks, Phantom Flex highspeed, and multiple rigs shooting at the same time on first and second unit. I built some new cameras rigs that can take you very close to the action. It’s won’t look so much like the action films we’re accustomed to, and the audience won’t have things thrust in their faces every five minutes. I hope it will be more painterly. If we get it right, it will be a cross between Blade Runner and Clockwork Orange.

Q: How do you feel cinematography is changing?

ADM: Fast. The palettes have always been there for there for the taking, but they’ve moved on from B&W, colour, 16mm and 35mm into HD. Ever since my graduation film I have never feared new technologies. I’ve always found them interesting to play with. Cinematography today is exciting, as we have far superior and a far more diverse range of image capture systems than ever. But this does make it harder, more complex for cinematographers. It’s a head-screw. If you can get you head around them, new technologies give you an incredible trump card into assisting as a responsible image maker, in trying to keep cinema alive, and to extend the possibilities of what the visual language is all about. It’s entertainment. It’s an art form. It’s our job, first and foremost, to push audiences. I am fascinated by technology, and feel we should be allowed and encouraged use new technologies – so long as you can argue the logic behind using them. It’s about honesty, being open-hearted, open-minded. We get employed because of our standards, expertise and knowledge, and our love for the job. But there’s a small percentage of something else that you bring, your potential variation in the cocktail, that will make the production different, and why they choose one from another. I feel I must not get lazy, complacent, nor go on autopilot. I have to keep reviving the child in me that asks, ‘How could I do this better, or how could I do this differently’.