FRESH PERSPECTIVES

A stripped back and imaginative crew reacted quickly whilst shooting on the move to capture the spirit of locations, intimate performances, and the blossoming bond between an uncle and nephew in C’mon C’mon. Robbie Ryan BSC ISC and writer-director Mike Mills relive the journey of creative discovery and the cohesion black-and-white brought to the story, uniting each of the cities visited.

“All art is autobiographical,” Federico Fellini said about the nature of his films in an article that appeared in The Atlantic in 1965. Such comments and advice shared by the Italian director have offered writer-director Mike Mills inspiration and guidance throughout his filmmaking career.

“He describes so beautifully being available to serendipity and to that which you didn’t expect which the film gods are bringing to your vision. I really live by that,” says Mills. “He talks about inviting all your failures, and viewing them as a strength, and how everything that went wrong helps show you how you are in the world, and that it’s a part of your film.”

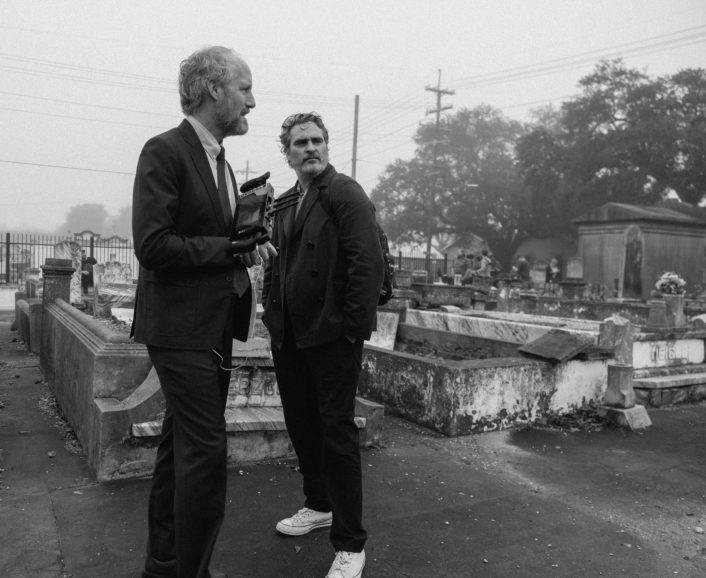

When penning his latest film, C’mon C’mon, Mills, like Fellini, drew from life experiences, as he has done for his previous films, and crafted a tender portrait of the relationship that evolves between a radio journalist, Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix), and his nephew, Jesse (Woody Norman), as they travel around the United States. This time, inspiration came from the transformative impact fatherhood has had on Mills. Through his script, he aimed to convey not only what it is like to be a parent, but also how a child experiences the world.

“Parenthood changes your heart and your life – it’s so intimate and personal,” he says. “There’s so much love but it’s also very private and sometimes doesn’t feel connected to the big social world you’re introducing this little person into.”

With this central notion driving the narrative, the Camerimage Festival Golden Frog and Audience Award-winning C’mon C’mon sees emotionally stunted but endearing character Johnny’s perspectives on life after he takes on the responsibility of caring for his eight-year-old nephew while the child’s mother devotes time to her husband who is suffering from mental illness.

Login to continue reading

This content is exclusively for digital magazine subscribers.

Start your subscription today, or login below to continue.

Possessing qualities of a traditional fable – an adult and a child walking through landscapes, trying to help each other see the world in a new light – and fused with documentary and road movie techniques, C’mon C’mon’s core concepts resonated with cinematographer Robbie Ryan BSC ISC’s attitude to filmmaking. “It fitted in with my way of shooting – a small crew in a road movie-like situation. Techniques from my previous road movie productions such as American Honey came into play,” he says. “C’mon C’mon isn’t your normal sort of drama; its approach is to be reactive and fast and to find beauty in something you didn’t see straightaway which suited me well.”

As the early buds of the idea for C’mon C’mon blossomed, the first image Mills envisioned – of a young person and an adult walking through the city – was in black-and-white. Having always wanted to venture into the realm of monochrome, the heartfelt story presented the director with the perfect opportunity to take the plunge.

Mills’ wish for the story to be told in black-and-white also attracted Ryan to the project. “It was quite ominous too because shooting black-and-white is absolutely sacred ground. But I knew the aesthetic Mike wanted to achieve would lend itself to black-and-white photography,” says Ryan, who is a fan of early black-and-white cinema. “Black-and-white films from the beginning through to the ‘50s and ‘60s was phenomenal. They created beautiful images with such technical skill, some even on tight schedules and low budgets. As almost everybody was doing it that way then, it was second nature, but some of that craft has fallen away now.”

For Ryan, black-and-white brings a cohesion to C’mon C’mon, uniting the cities visited on the impromptu road trip through New York, Detroit, New Orleans, and LA and focusing the core of the film. “The audience knows each chapter heading, or city is different, but because they’re in black-and-white, it eases them in a bit more.”

From the beginning, Ryan and Mills discussed how black-and-white can be used as a trick to make a film look pretty. “We didn’t want to fall into that trap,” says Mills. “Robbie wanted the black-and-white to have a lot of weight to it.”

Mills also wanted very little art direction and for the film “to feel authentic, like it was actually taking place in 2019” when it was shot, which he believes black-and-white helped achieve. “I once heard director Mike Nichols describe black-and-white as not being reality but being about reality. It gives you this cinematic base and flexibility to get into a more fable, art, and story-focused feeling.”

In contrast to a traditional fable structure, the film also ventures into documentary territory and adopts a naturalistic approach for scenes which see Johnny interview teenagers about their views on the world. “Feature films love contradictions; they create a lot of energy,” says Mills. “I felt this contradiction between a classic fable and cinéma verité would energise the filmmaking.”

Visual sensibility

Revelling in exploring a location and taking stills to determine how they translate into cinematic imagery, Mills carried out many of the recces prior to Ryan coming on board. He photographed key locations that would provide the backdrop for the expanding story, from cityscapes and iconic landmarks such as Santa Monica Pier through to friends’ apartments. “As Mike’s also a graphic designer and excellent photographer, he has a great visual sensibility,” says Ryan, “so that aspect of the project was advanced from very early on.”

Exploring a director’s ideas “and then fitting into them” to ensure their vision is realised in cinematographic form is a stage of filmmaking Ryan relishes. “Mike was very thorough and definitive in what he wanted visually, and I could easily sync up with his thinking. His storyboard of photographs he’d taken was like a collection of chapter headings he wanted to incorporate scenes around. Some of those shots, such as the image of the pier, feature in the film.”

Mills admits he is more focused on composition and “what’s happening at the edges of the frame” than on light or colour. “Robbie took that photography, and really ran with it and added to it – he was an excellent collaborator in that way.”

What was initially planned as a five-to-six-week shoot turned into four months of filming, with multiple stages of prep. “Rather than doing all the prep at the beginning of the process, we prepped for four weeks in LA and then shot for two or three weeks in that location before prepping for two and a half weeks in New York and then shooting there for two weeks, and so on,” says Ryan. “It was the first time I’d worked like that, and it was an interesting process.”

While on their voyage of visual experimentation and discovery, the filmmakers were influenced by the character balance and simplicity of Wim Wenders’ 1974 black-and-white road movie Alice in the Cities (lensed by Robby Müller NSC BVK) which is about a man taking care of a young girl. They were also inspired by Japanese filmmaker Shōhei Imamura’s beautiful black-and-white photography capturing family life; the openness and gentleness of French composer Erik Satie’s piano pieces; and the editing, story structure, and cinematic language of Ermanno Olmi’s 1963 feature Fidanzati (The Fiancés).

The work of Gordon Willis ASC has been a consistently important filmmaking motivation for Mills. “There’s a warm observational quality in his compositions and he was so talented at combining things that feel accidental and non-aesthetic with those that feel highly authentic,” says Mills. Ryan experimented with this in C’mon C’mon – combining iconic imagery that could be a scene from a postcard with shots that are more accidental or documentary-like.

“Robbie’s great at that. He’s so brave and has such a breadth of film experience and film taste,” says Mills. “He’s not afraid to capture shots that aren’t over aestheticised. You can’t always have backlight and a pretty shot. Sometimes you need to find different levels. With some DPs, every single shot must be pretty, and it kind of puts your film to sleep.”

An empowering experience

As Mills wanted a softer, more tonal black-and-white and to “shoot endlessly; turn the camera on and keep it running”, the filmmakers decided to capture C’mon C’mon digitally. With performance being central to the film, it was “essential to be ready, willing, and able to capture anything the actors did at any time.”

Ryan would shoot some documentary-style scenes and “needed to be nimble to run around with the camera”, so he opted to shoot with the ARRI Alexa Mini. “The simpler the camera set-up, the quicker and more easily I could capture scenes, and the better the results would be,” he says. “The Alexa Mini is a workhorse, and I was already familiar with its strengths and usability, having shot with it many times.”

An advocate for marrying older lenses with digital formats, Ryan selected a Panavision package comprising PVintage Prime lenses and Primos, capturing the documentary footage on the 19-90mm Primo Compact Zoom. “I love Panavision glass and the Primos and PVintage combined were such a lovely combination for this film,” he says. “The compact zoom was great for when we had to get in and out of the interviews quite quickly and couldn’t wait to change the lens.”

Ryan invited Mills – who has not tended to venture beyond a 27mm lens in his previous work – to explore wider filmmaking horizons. “I’d shot The Favourite on a 6mm lens, but not many directors go that far. For this film, I convinced Mike to go a bit wider with a 24mm,” says Ryan.

Mills was particularly enlightened by the lesson he learnt from Ryan when capturing a sequence featuring a wide shot of Johnny and Jesse by Manhattan Bridge. “It’s a great shot, but then in the reverse shot they are framed from their knees to above their heads while standing in front of beautiful buildings. Robbie convinced me to shoot that on 24mm – a little wider than I usually would like – and it turned that shot into such a classic, beautiful image.”

Close-ups and medium close-ups are where Ryan really shines, according to Mills: “The way they are lit and framed is so masterful and subtle and shows a real depth of Robbie’s taste and talent.”

To fit in with the road movie approach, Mills chose to make the film with a small core crew. “Credit to Mike for coming up with that idea because it worked incredibly well,” says Ryan. “It was really unusual and special – we were like a travelling carnival and really bonded over that.”

Similarly, Mills enjoyed the team and kit’s small footprint, how simple the set-up was, “and that there wasn’t anything overly fancy or precious about Robbie’s process. We were so light we could be in New York City in the middle of rush hour, use a camera with a long lens 100 feet away from Joaquin and Woody, and no one noticed we were filming.”

Capturing “natural performances and making the actors feel alive” was essential, whilst playing with the thin line between shooting and not shooting. “You try to make it feel like you are playing,” says Mills. “Often the cameras were on, and people wouldn’t know. But Joaquin always knows when you’re ready to shoot and will just start doing a scene. I like it when there’s that grey area and you can slip in and out of it at any time.”

Ryan was the “perfect partner” for achieving this. Like Mills, he prefers not to over plan, favouring being open to spontaneity and unexpected occurrences which might enhance the production. Phoenix’s way of working complemented this approach. He was happy to change a scene on-the-fly and sometimes completely removing the dialogue if it would benefit the storytelling.

“It was the most flexible, changeable, and intuitive process I’ve experienced, and it was empowering. That takes a lot of bravery from the crew and cast as well as the experience to know you can achieve the scene in a new way,” says Mills. “If you plan too vigorously, you uninvite that magic. You’ve got to be ready for what the film gods show you on the day.”

Phoenix’s involvement in C’mon C’mon was one of the factors that initially attracted Ryan to the production. “I’m a fan of his work and thought how often do you get a chance to shoot a Joaquin Phoenix film? Filming him and Woody together every day was a highlight,” he says. “That’s why I love operating so much; I really miss it if I’m not near the actors. My idea of hell is being on a remote head in another room and trying to figure out what the camera is about to do.”

To capture the performances, Mills wanted to keep the camera moving but avoid using a large dolly and track, so a tiny dolly and track system was created which was meant to be inconspicuous. “But this became even more awkward,” says Ryan, “so I ended up using a slider a lot which I nicknamed The Meat Slicer. Through this process I also became even more appreciative of the artistry of gripping.”

Preferring camera tracking to be like a “manifestation of the audience’s attention” rather than motivated by the action, Mills required movement to be more random, observational, and slightly abstracted from the scene. “It’s too manipulative if the camera relates too much to the action,” he says. “It’s obtrusive; like interrupting someone when they’re talking. I just want us to be outside, watching.”

And although Ryan and Mills initially wanted to avoid Steadicam for certain scenes, they later realised it would be necessary to achieve the desired look. “It was a wise decision and Steadicam operator Nick Müller – who also did some second camera operating – was amazing. Everything was shot using some sort of tripod, dolly, or Steadicam,” says Ryan. He also commends the talent of 1st AC Norris Fox; shadow DP Jon Chema; and cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt, who shot additional scenes required to fit in with changes made to the story following the edit, which took place during lockdown and meant Ryan was unable to travel to the US due to pandemic restrictions.

Freedom to explore

After shooting the drama sequences each day, an even more stripped-back crew – comprising Ryan, Mills, 1st AC Norris Fox, and sound recordist Philip Bladh – filmed sequences of Johnny interviewing teenagers. When shooting these scenes, which featured real people, Ryan “tuned into different documentary sensibilities”, being mindful to be respectful of their space. He found the experience “refreshing and a joyful way to create the film”.

“None of the children really knew who Joaquin was and he loved that. The film just wouldn’t be the same without him – he was so warm and really engaged with the kids,” he says. “We shot just before the pandemic, and it would be interesting to see what the kids’ responses would be now when asked about their worries. Some mentioned concerns about pandemics, but nobody saw quite what was coming.”

Another invigorating creative outlet for Ryan was shooting reportage footage at key locations based on bullet points Mills provided outlining the places he had found whilst scouting. “It was just Mike’s assistant Joe Nankin and I travelling around in a car, stopping at each place to capture beauty shots or just shoot life. It was liberating to have the freedom to go and film interesting locations in all the different cities.”

Mills also highlights the reportage sequences as some of his most treasured sequences in the film. “I love that kind of photography and the sense of scale in Robbie’s landscape shots mixed with the narrative is so important. Doing it that way was a smart move and better than if I was standing there over his shoulder.”

Despite being a minimalist, Mills adores large-scale photography. And while the heart and soul of his movies are the intimate scenes, he wanted to combine these with epic shots captured from an aerial viewpoint. “I think the two are interwoven and I wanted to show how that intimacy can be social or historical. For instance, the scene where Jesse is being given a bath is happening in the middle of New York and in a moment in history shared with all these other people. To me, that is the story. So, I also wanted to capture it from a different vantage point,” he says.

“I love a drone shot or a low helicopter shot, being 100 feet up, cruising over the city. And as the aerial sequences are in black-and-white, which you don’t see much, I think this adds a fresh quality.”

Ryan applauds Mills for his intelligent use of the aerial footage and how the soaring shots – captured in LA, New York, New Orleans, and Detroit – seamlessly slot into the visual language and narrative structure: “I find drone shots are always so expressive and impressive which can make it difficult to follow up with the next drama scene. The way Mike used them was so judicious and clever – they’re like tableaus and not overused.”

The treasure of the shoot

Striving for authenticity, Mills wanted to keep many of the apartments and houses in their original state to ensure interior locations were as true to life as possible. The only exception was Johnny’s apartment in New York City which was an empty shell and required decorating. By that point, the team had developed a visual language from shooting in other living spaces and used photographs Mills took of friends’ residences as a model. Working with production designer Katie Byron, Mills aimed to keep everything realistic because he “wanted all the layers, textures, and strangeness of real life rather than a very art-directed life.”

Alongside Byron, key grip Julien Janigo, and gaffer Nghia Khuu, Ryan determined which practicals would feature in each setting, and whether it was necessary to black out windows. “People might think of Robbie’s amazing use of natural light when working with Ken Loach or Andrea Arnold,” says Mills, “but in my film he was also working with many night-time interiors and because we were shooting with a child, we often had to play day for night and black out windows.

“Robbie created the whole atmosphere of that space, and it looks so natural. You don’t have any sense that it’s constructed. It’s beautiful, iconic imagery that harkens back to old black-and-white cinematography, and he did it with very little kit.”

Ryan also credits Janigo and Khuu for this: “For example, in the scene where Jesse first meets Johnny in a lovely, big, old house in LA we needed to black it out and then quickly take down the blackout. A tiny crew was responsible for it, and they did it with skill and at speed.”

Outside of this, Ryan adopted his renowned naturalistic approach, mainly working with natural light as the crew was often “on the move and needed to enhance what was already there.” The small lighting package he also relied on mainly comprised of LED fixtures including LiteGear LiteMat2, with some tungsten products such as Dedolights.

“The versatile and tough LiteMat2 was a great friend on the shoot as it can take a battering which is great because I can be quite rough with lights,” says Ryan. “I’m also a big fan of practicals and black-and-white can be helpful in that respect because an overexposed practical in monochrome is such a beautiful thing.”

Following the shoot, which was completed just before the pandemic reared its ugly head, MPC colourist Mark Gethin was joined in LA by Mills for a grade which the director considers among the most creative he has been a part of. “Grading black-and-white is so different to colour. It’s about light and dark and shaping your focus,” Mills says. “It’s a bit like drawing or painting; modulating where your attention lies.”

Gethin introduced Mills to LiveGrain software which adds a three-dimensionality to the image. “It was such an interesting process to work with an algorithmic grain which is intelligent, subtle, and reacts to the light,” says Mills.

Having also graded the director’s previous film 20th Century Women, Gethin was keen to play a part in C’mon C’mon when Mills mentioned he was hoping to finish in black-and-white. “Mike is always very involved in the grade, so we were constantly tweaking and trying things out in the grade. We were conscious not to make it feel too contemporary or too of a certain period,” says Gethin.

“This was such an intimate, soulful movie. It was beautifully shot by Robbie and had a lovely, soft feel to it. So once we found a certain weight or density to the film, we spent a lot of time using windows and keys to pull forwards and push back certain elements of the frame. It was almost like a dodge and burn technique in photography, but we were always very aware not to make it feel too pushed in any way. Mike likes to make the actors prominent, so a lot of focus was on pushing faces and eyes before the subtle film grain was added using LiveGrain.”

As well as the technical discoveries made; the experiences on the road made an indelible impression. “It was just fascinating to see the four polar parts of North America and how vastly different each one is,” says Ryan. “The people we met and the environments we filmed in were extraordinary.”

Mills also cherishes the variety and excitement of making a movie on the move and believes any challenges encountered – from the biting cold of Detroit through to securing permissions to shoot drone footage in New York City – are all part of the filmmaking conversation and should be embraced. “In line with Fellini’s view on making movies, it’s just the world telling me how the film needs to be. Capturing remarkable locations as we worked in each city was one of the real treasures of the shoot.”