NVIZ were approached to previs sequences on The King’s Man, the keenly awaited origin story of the popular Kingsman films, directed by Matthew Vaughn.

The NVIZ team, led by supervisors Janek Lender and Hugh Macdonald, worked closely with the late Brad Allen, legendary Supervising Stunt Coordinator (Kick Ass, Kingsman: The Secret Service) and the film’s overall VFX supervisor, Angus Bickerton (Kingsman: The Golden Circle, Total Recall), primarily on the Goat Climb sequence, a breath-taking and complex scene close to the end of the film and also the bi-plane sequence.

NVIZ had the pleasure of working with both the stunt team and Bickerton on previous projects, so they knew the process would be collaborative as well as technically and creatively challenging. In addition, as Lender says, “It was great to be working with the stunt team. It’s such a good use of the virtual camera system technology in the process of storytelling.”

In the Goat Climb sequence, Ralph Fiennes’ character, The Duke of Oxford, is parachuted onto the top of a mountain. He doesn’t quite make it and his parachute gets caught up with an outcrop of trees on the side of the cliff. He’s woken by mountain goats, hence the name. From a stunt point of view, this was going to be a complicated process.

Traditionally, in setting up for a stunt like this, the stunt performers film various stunts and sequences which are then edited together to provide the director with an idea of how the stunts might work before principal filming. Allen, who had a long history working with Matthew Vaughn, wanted to make sure that The King’s Man was filmed in a way that worked for the stunts.

From previous experience, he knew that stunt planning in previs could benefit from earlier input from the stunt team. In addition, the Goat Climb sequence takes place at the top of a cliff, and Allen was also aware that filming in a stunt studio was not going to lend the ambience that Vaughn would be happy with. With all this in mind, the production came to NVIZ to create a virtual stunt vis of the sequence.

When presented with the concept, NVIZ knew the basic route they were going to take. Internally, NVIZ were already developing ARENA, their virtual camera system as a tool and knew it was ideally suited to The King’s Man’s requirements.

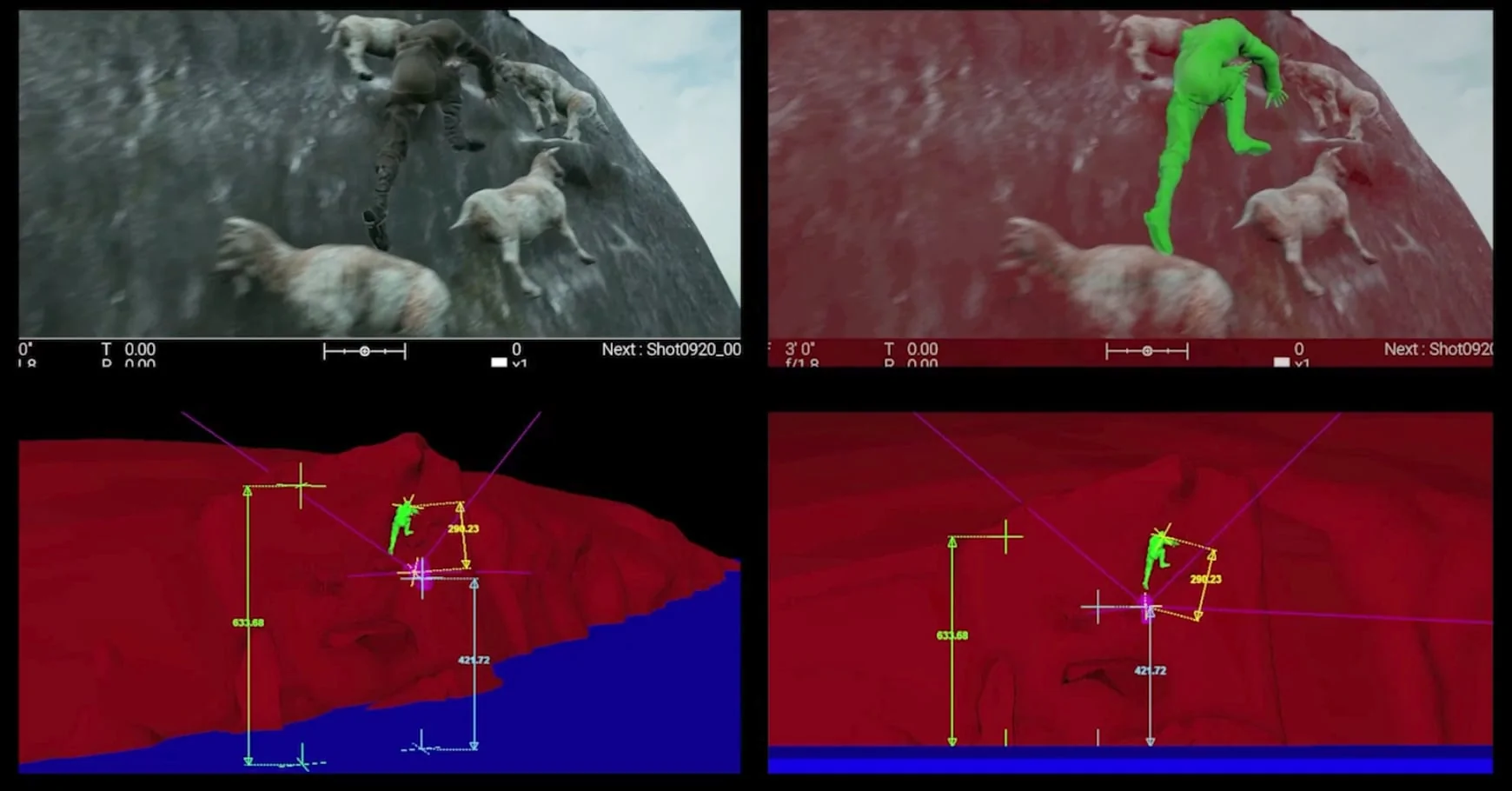

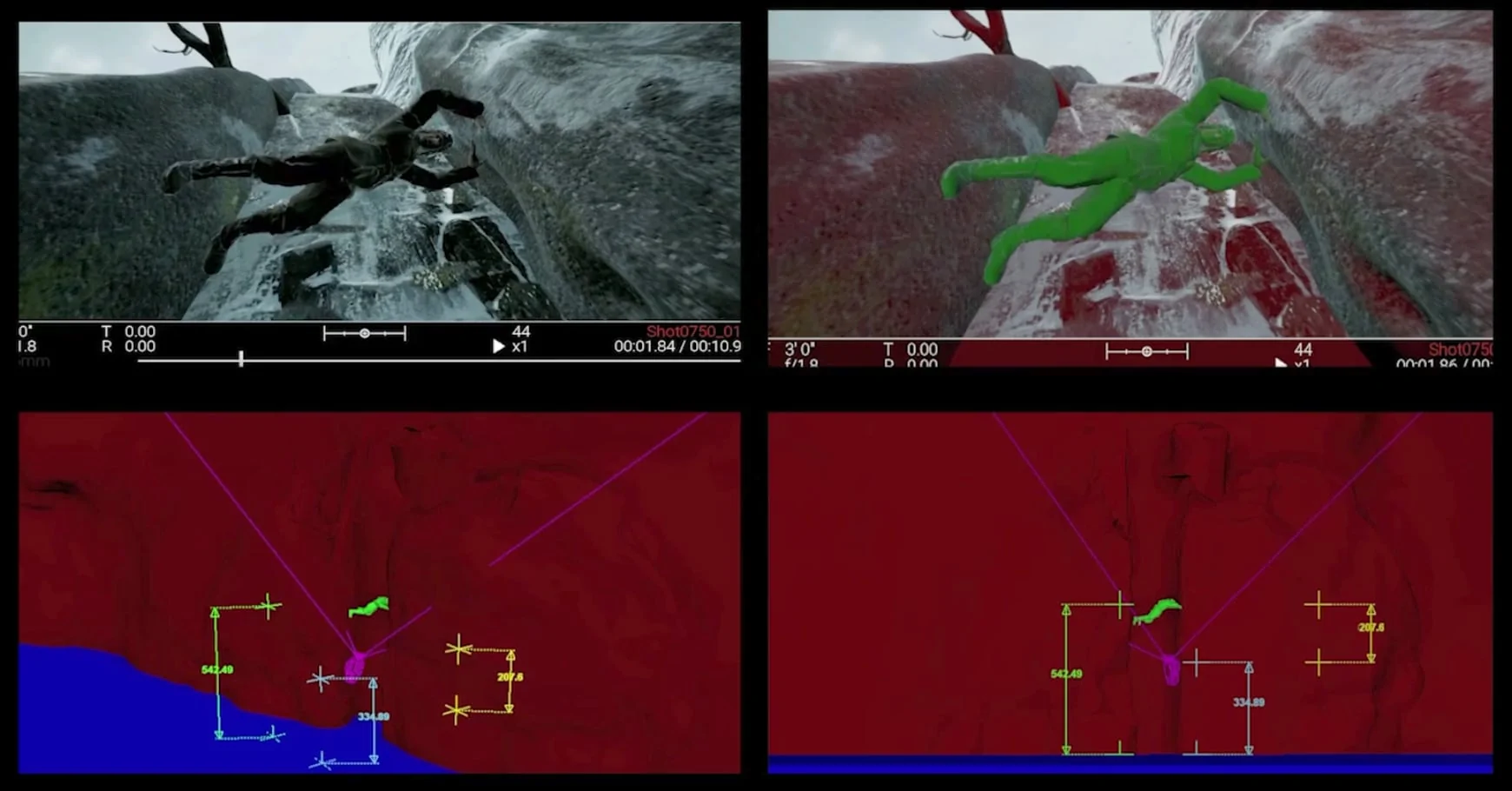

The sequence required them to capture a performer climbing. Having explored various options, the team opted for a combination of optical and inertial, using optical mocap around the performer’s waist to keep tabs on where he was on the wall, with inertial mocap to capture the performer’s pose.

Once the mocap was captured, the NVIZ team imported the mocap data into the virtual camera “world” in order to film the scenes. While they considered shooting with ARENA at the same time as the stunt was performed, it made sense to make it a two-step process. This was mainly because it took a few iterations to get the camera exactly right, which would have required the stunt artist to keep re-performing his stunt. As a result, they recorded his moves and then played that back in the virtual camera world.

The beauty of ARENA is that it provides a hands-on experience for the filmmaker. Once the process got going, it was operated by the production’s Action Designer, Yung Lee, who filmed and edited the stunts together. Lee was set up in a corner of the stunt warehouse, and once the stunt crew had captured the stunt performance, Lee would use ARENA (which was using the HTC Vive tracking system and Unreal Engine), to film the move in the virtual world.

ARENA enabled Lee, essentially as the camera operator, to be several times bigger than the cliff and performer; as it allows the operator to change scale versus the set and performers and presents other and various options for the ways the camera operator can control the camera. Says Macdonald, “ARENA gives one the ability to have camera moves that feel real, feel handheld, but without having to have all the rigging, cranes, dollys etc that you would need on a real film set.” He goes on; “In this specific context, ARENA gave the 2nd unit director, and the stunt team, the ability to visualise what the sequence would be like on location, in a rough version of its final form; with the height of the mountain, how it looked, the environment etc. This meant that they could present it to the director as a realistic presentation of what they would shoot.” The process gave all the creatives a tangible feeling of what they would shoot before they got to the really expensive part of shooting for real.

In addition, ARENA gifted the production with time to “play” with the setup; moving camera angles physically, trying out different angles, and exploring new angles they hadn’t thought of before. Much like a director and cinematographer would do on set through the viewfinder to find the sweet spots.

This level of flexibility can sometimes be more difficult to do in more traditional previs, where the director or VFX supervisor is once removed, giving notes to a previs artist who shifts the camera around with a keyboard and mouse. “ARENA offers the possibility to make changes along the way, but still cut together and build a sequence in days and weeks, rather than months.” says Lender, “in addition the production can go in afterwards to add or change shots. In The King’s Man’s case, the team came into our offices to rework some shots. All of which is extremely cost effective for the production’s budget.”

When The King’s Man production team headed to set for the Goat Climb, they were armed with a well worked out story, in the shape of a mixed media output of storyboards, previs, ARNA output etc, in one cut. All of which allows for a much more creative process for the filmmaker and saves time and money when the crew arrives at the real shoot.

In addition to the Goat Climb, NVIZ also worked on previs for a sequence featuring Ralph Fiennes’ character walking along the wings of a biplane before parachuting off.

The NVIZ team, led by CG Supervisor, Sam Churchill, used a digital version of a rig provided by Robomoco, created animations that would simulate the effect of a spiralling plane and test the limitations of the real rig, including the collision issue. The animation moves were imported into the robot arm rig and a series of dry runs were performed, progressing from first; an empty robot, then with the wing attached and finally with the stunt artist inside. “It’s always interesting to watch someone climb into a rig and test a program we’ve written based on script requirements,” says Churchill, “there’s a lot of responsibility.” But his hard work testing the animation and rig had paid off as the programs ran smoothly and successfully.