Screen Burn

For around half its life the cinema has faced a series of rivals that have threatened its existence. TV in the ‘50s, the ‘80s home video boom and, most recently, the streaming revolution.

Each time it has managed to adapt or even reinvent itself to survive by offering new technologies or changing its image. And there has always been James Bond, the Rebel Alliance and now The Avengers to come to the rescue.

The coronavirus pandemic, however, poses the greatest threat to the future of the cinema business and even 007 himself is not willing to take on the fight to save it. With film production shut down (but some post-production continuing) and cinemas closed during lockdown from March this year, 2020 suddenly looked grim for a sector that has long had to deal with uncertainty.

Ironically, before Covid-19 hit, the cinema sector had been enjoying one of the most successful periods in its history. At the Digital Cinema Summit (DCS) in Amsterdam during early February the hot topic was what impact streaming was having on movie theatres, not the effects of a pandemic, the impact of which was only just becoming apparent.

The overall conclusion was that the death of cinema had been predicted many times before, but it would, as it always had, sustain. No one, of course, could have foreseen what would happen only a few weeks later. With lockdown in place and the cinemas closed, distributors set about rescheduling their big releases for later in the year. The highest profile of these was No Time to Die (DP Linus Sandgren FSF ASC), which was due to open in April. It was pushed back to November, when it was hoped cinemas would be open again. But even though cinemas did reopen when the lockdown was lifted, the 25th Bond film was postponed again until April 2021. Another biggie, Dune (DP Greig Fraser ACS ASC), set for December, is now slated for October next year.

The effect of these decisions was immediate and drastic. Cineworld decided to keep its screens shut until next year, while both Odeon and Vue are restricting screenings, with some cinemas open only at weekends. Independent and boutique cinemas are attempting to keep operating but with very few films being released, they are finding it difficult to attract audiences. Christopher Nolan’s Tenet (2020 DP Hoyte Van Hoytema NSC FSF) was the highest profile release. After six weeks of global circulation it made £235m – terrible compared to other Nolan pictures but covering its production budget of approximately £154m in a pandemic looks like good going.

This experience has put the big studios and distributors off releasing what were potentially hot properties. Which has left the field open for lower budget and indie films. Some directors have taken to novel methods to get their work seen. Independent director Guy Davies called up cinemas offering his low budget coming-of-age drama Philophobia (2019 DP Stefan Yap), which has ended up in 50 UK cinemas, including Vue screens and even got a Leicester Square showing.

The foundation of the business remains strong. We believe that once this is all over, the public will want to embrace the communal big screen experience more than ever.

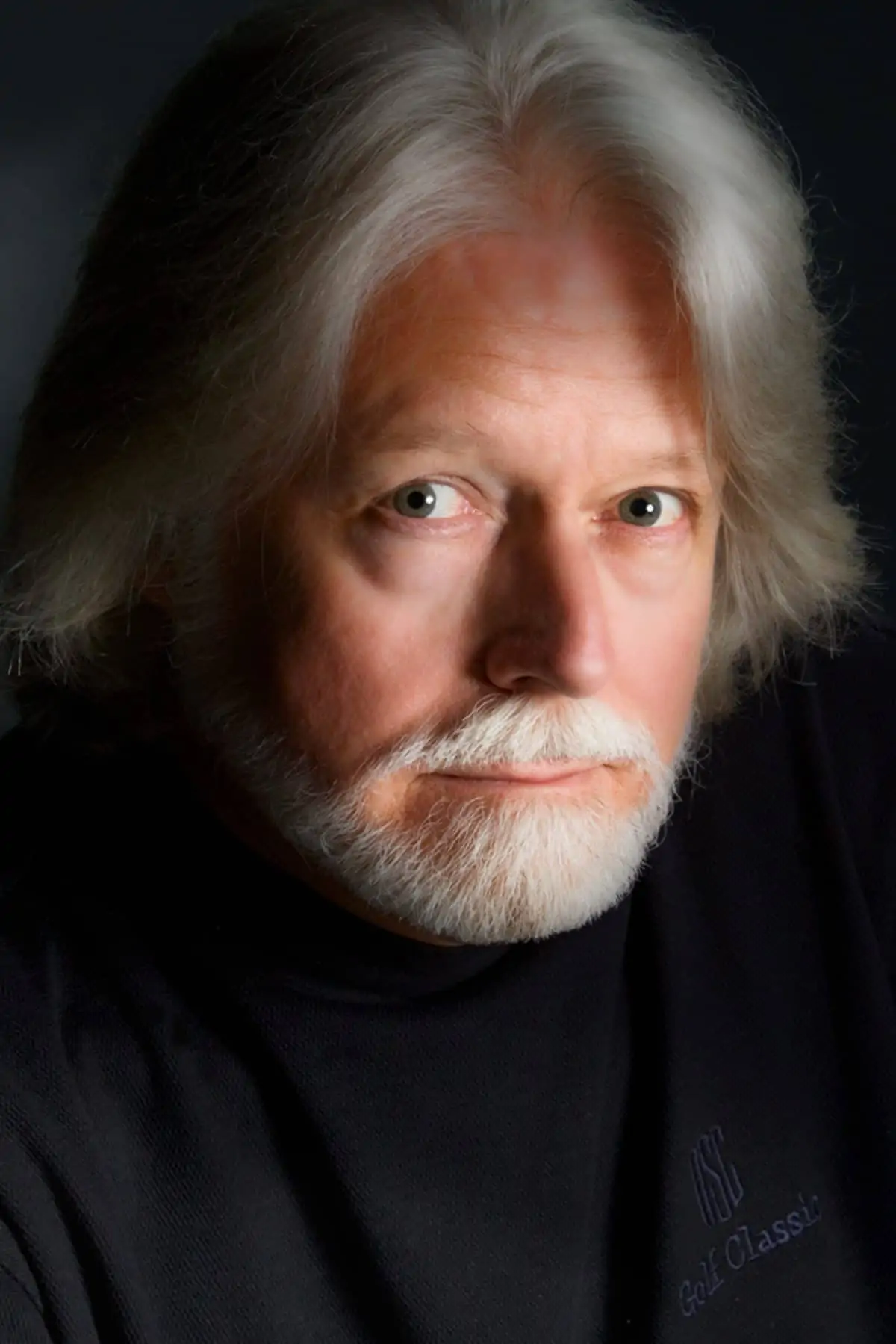

Phil Clapp – Chief Executive, UK Cinema Association

Despite such energy and persistence, the outlook is still bleak for cinema exhibitors. “The entire UK cinema sector is experiencing some of the most challenging times in living memory,” comments Phil Clapp, chief executive of the UK Cinema Association. He adds that the operators who did re-open in July have implemented safeguards and audiences have returned. “Our most recent survey showed that 93 per cent of cinemagoers found their visit safe and enjoyable,” he says. “The challenge cinemas face is a result of factors over which they have little influence, specifically wider public confusion concerning the restrictions that apply to cinema-going and a lack of major film titles.”

On this last point, Clapp says the decision by US studios to take around 46 “significant” releases out of this year and into 2021 will account for an estimated loss of £0.5bn at the box office. “These are decisions not taken on the basis of any concerns around the safety of UK or European cinemas,” he explains, “but because those films cannot be released simultaneously across the globe when the West Coast and, in particular, East Coast of the US remain for the most part closed. As a result, admissions/box office is approximately 80 per cent down on the same point in 2019 and the total annual figures are over 70 per cent below those for last year.”

Ben Luxford, head of UK Audiences at the BFI, says the situation is hitting independent exhibitors, big operators and distribution companies hard but in different ways. “Independents saw any reserves they had to sustain them through quiet patches quickly exhausted months ago when they had to close completely,” he explains. “The larger circuits have an economic model that relies on a continuous supply of content to show on multiple screens, which is not available right now, while distributors are trying to balance the costs of launching releases with being able to reach audience targets.”

BFI statistics project that the total cinema box office for this year could be 25 per cent of what it had been in 2018 and 2019. To cushion such a loss, the BFI has repurposed its Film Audience Network funding from the National Lottery of £1.3m to offer critical relief to UK exhibitors. It is also managing the £30m Culture Recovery Fund for Independent Cinemas in England on behalf of the DCMS (Department of Culture, Media and Sport). Another priority, Luxford says, is to ensure production continues so there are films to show. “We have entered into an interesting partnership with BBC Film to ensure seven new British films, which the BFI Film Fund has supported in development and production. We are continuing to prioritise support of the production sector and are highly concerned for freelance workers, as well as every part of our ecosystem, through to cinemas and broader screen and international exports.”

The outlook may be bleak right now, with the possibility of some cinemas that are closed never re-opening. But Phil Clapp thinks what could come out of this is a better “balanced” film slate, with less dependence on major US studios, creating more of a showcase for domestic and European production. “The foundation of the business remains strong,” he concludes. “We believe that once this is all over, the public will want to embrace the communal big screen experience more than ever.” It is certainly to be hoped that this is no time to die for cinemas.