Heart of Darkness

Sean Bobbitt BSC / 12 years a slave

Heart of Darkness

Sean Bobbitt BSC / 12 years a slave

BY: Ron Prince

Variously described as “blistering and brilliant”, and “a new, movie landmark of cruelty and transcendence", 12 Years A Slave looks set to storm the headlines and, in all probability, the 2014 awards season when it goes on general release.

The $20m feature film, directed by Steve McQueen, written by John Ridley, with Sean Bobbitt BSC the cinematographer, is adapted from the 1853 autobiography Twelve Years A Slave by Solomon Northup. Northup, a free black man, was kidnapped in Washington DC in 1841 and sold into slavery. He then worked on plantations in the state of Louisiana for 12 years before his eventual release.

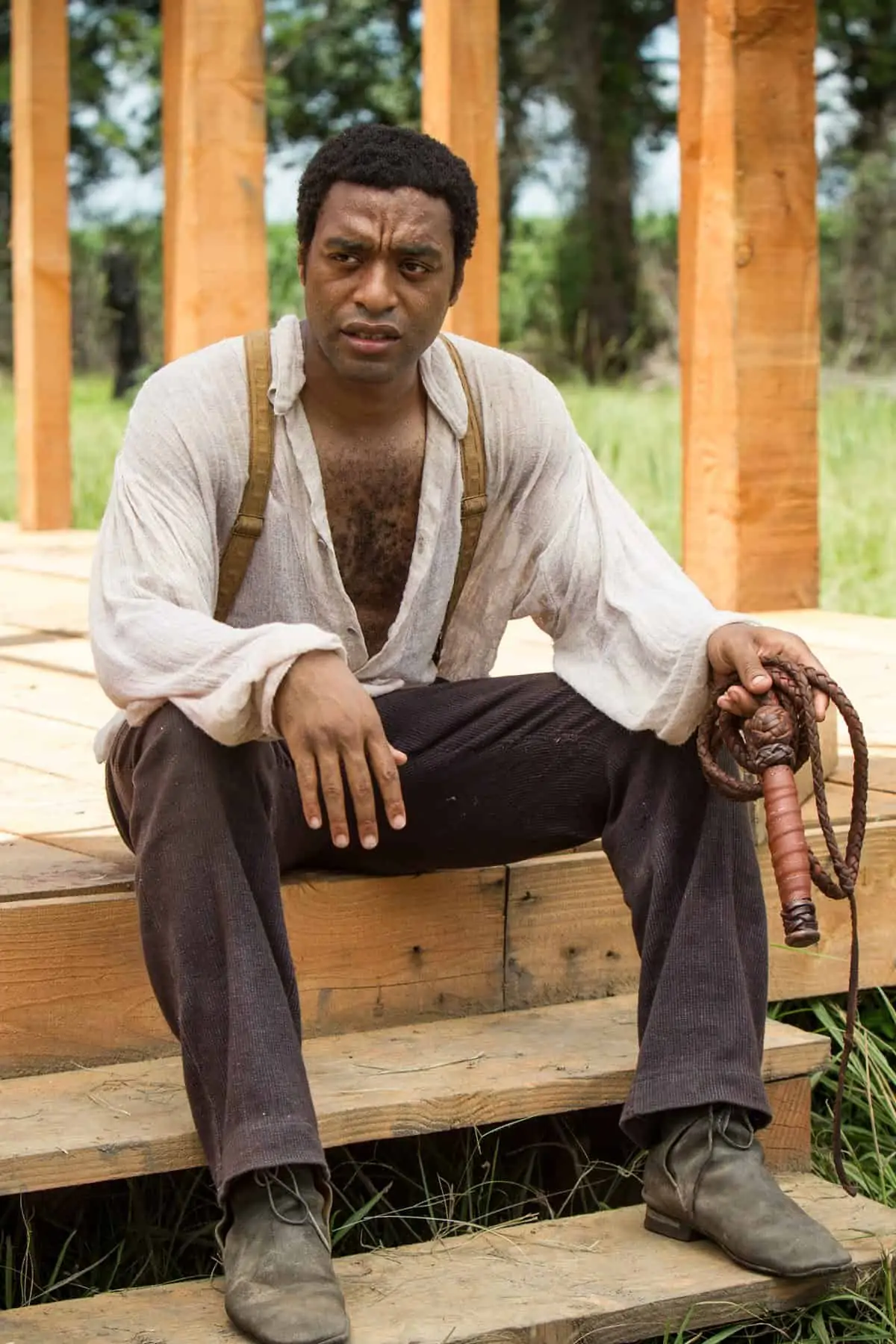

The cast includes Chiwetel Ejiofor as Solomon Northup, Michael Fassbender as Edwin Epps, a cruel plantation owner, Benedict Cumberbatch as William Ford, a Baptist preacher and slave owner, Paul Giamatti as slave trader Theophilus Freeman, Lupita Nyong'o as Patsey, a slave on the Epps plantation, and Brad Pitt as Samuel Bass, a Canadian carpenter. The seven-week shoot began in New Orleans, Louisiana in June 2012 concluding mid-August.

During its limited release at film festivals, the movie has already been lauded by critics and audiences, with praise for its acting, Steve McQueen's direction, screenplay, Bobbitt’s cinematography, production values, and its extreme faithfulness to Solomon Northup's eponymous autobiography. Here Bobbitt talks about his cinematographic work on a movie about a life that gets taken away, but which ultimately lets us touch what life really is.

How did you come to get involved with 12 Years A Slave?

I’ve been working with Steve McQueen for the best part of 12 years – firstly on his art installations, and then I shot Hunger (2008) and Shame (2011) with him. We’ve become great friends and see each other regularly, even though he lives in Amsterdam and I live in London. He’s such a fascinating character. A kernel of an idea will appear, we discuss it, and then it may go away for quite a while before it comes back again fully-formed. But 12 Years A Slave was quite different, it didn’t have a long gestation. Steve’s wife found Solomon Northup’s book, he was hugely interested in making a film about slavery, and it was all very fast from there. Steve was talking about it before we started making Shame. We started on 12 Years A Slave as soon as Shame was released in 2012.

What appealed to you about 12 Years A Slave?

Slavery is an issue that has been forgotten, and most of the films that have been made about it have been watered down, to say the least. So it was time for something like 12 Years A Slave. But my interest was also in continuing to work with Steve. Every cinematographer is looking for a brave, original, respectful and loyal director. And when you find that person, you want to stay with them. It was a no-brainer for me when Steve mentioned 12 Years A Slave. The epic scale of the film, the visual possibilities, complexities and challenges were very exciting.

Did you read the original book Twelve Years A Slave?

I try not to read books that scripts are based on, for the simple reason that my loyalty, intellectually and spiritually, is to the script and not the book. If I had read the book, I would identify with elements in the book, and would probably come into conflict with those. The template I prefer to work from is the screenplay, to understand the desires of the director, and not have anything else in my head. For me, that’s the starting point from which cinematography should grow.

When you first discussed the look of 12 Years A Slave with Steve McQueen, how did you envisage the film?

We nailed-down the look early-on. Although 12 Years A Slave is based on a true story, we were making a work of fiction. We wanted to stay away from a grungy documentary style – no frippery, nothing to distract the audience from being completely engaged in the story. Our two watchwords were “simple” and “painterly”, and we held on to those throughout the production.

What research did you do? What creative references did you look at?

Every director is different and every project is different. The great advantage of having worked with Steve on so many productions over the years is that we share an understanding. We can leap in quickly to the depth of the story. Steve is very good at presenting references that are relevant – paintings, photos, films, installations. He had a really broad selection for 12 Years A Slave, although nothing specific about slavery – from bizarre and little-known Korean films, to a PBS documentary series about the roots of jazz, as well as contemporary American artists like Cara Walker. Her work uses silhouettes, touches on slavery and sexuality, and is quite anarchic and very in-your-face. These we all very interesting references for me.

We had a truly fantastic art department, lead by Adam Stockhausen, who did an awful lot of research. They came up with early photographs from that period – of slaves, slave shacks, plantations and New Orleans – that were truly remarkable as visual references. We got a concrete idea of how people dressed and how they lived, and this sparked the look and feel of the film. It was really helpful to have that visual verisimilitude and to bring that to the screen.

"Every cinematographer is looking for a brave, original, respectful and loyal director. And when you find that person, you want to stay with them."

- Sean Bobbitt BSC

Tell us your reasoning behind your choice of equipment? What aspect ratio did you select?

Because of the epic nature of the story, and what we wanted to produce, we knew from day-one that we wanted to shoot on film. Digital never entered our thinking. It followed that 2.40:1 would be right aspect ratio to give us that epic sense of scale, and sheer production value. As a further consideration, the environments we’d be working in were harsh, with temperatures into the early 40C and truly biblical thunderstorms, and I knew film cameras would hold up.

What kit did you choose?

We shot using ARRI LT and ST cameras in 4-perf, hired from ARRI CSC in NY. I have used these a lot and trust them implicitly. The LT is nicely balanced for handheld work, and is really rugged and reliable. The ST is pretty much bulletproof. I used a full set of Cooke S4 primes, from 14 to 150mm. I like the look of them, and knew they would lend themselves to this production. The S4s have a forgiving softness, compared to other primes, but when projected they have equal if not better resolution, and a nice warmth. I also used an Angenieux Optimo T2.8 24-290 zoom. Lights were supplied through gaffer Michael McLaughlin. The grip equipment was supplied by key grip Nick Leon through Orange Whip Grips. Dollies, cranes and remote heads came from Chapman Leonard Studio Equipment.

Which film stocks did you select?

I chose to shoot the daylight exteriors using Kodak Vision3 50 Daylight (5203), and some daylight interiors with Kodak Vision3 250 Daylight (5207). They are both astounding, clean stocks with fantastic colour. For nighttime and candle-lit scenes I used Kodak Vision3 500 Tungsten (5219), pushed one stop to 1,000 ASA. I’d quite often supplement the candlelight with a combination of simple chinaballs, 40W light bulbs and photofloods dimmed right down to match the colour temperature of the candles themselves. I have to say that the latitude of modern film stocks, combined with what you can do in the DI, means that the challenge of shooting dark and light skin in the same frame is much easier these days.

How much time did you have for prep/pre-production? What was the working schedule?

I had five weeks of prep, and those five weeks go fast. The first two weeks are the most important, as that’s the time when you have full access to the director, when ideas are discussed and refined. After that the demands on the director mean your access becomes less and less, and your own workload is increasing too. We shot five day weeks mainly, standard 12–hour days, and didn’t go over very often. We rarely do on Steve’s films. He’s very decisive on-set, and we tend to shoot fairly sparsely. Many Hollywood productions tend to shoot a lot of coverage, and that means long hours. But we shot just what we needed.

Where did you shoot?

I’d say 95% of the film was shot on location, in working plantations, in the countryside around New Orleans. We did most of the recce’s during the first two weeks of prep, became highly-aware of the visual possibilities the locations offered, and that sparked a lot of creative discussion. Some of the locations were quite haunting. There is one scene in which Solomon makes a break for freedom, only come across a couple of black slaves being hung from a tree. I found a tree for this scene, and quickly learnt from the present owner of the plantation that slaves had actually been hung from it in the past. Their overgrown graves were still there beside it. We used that same tree for the scene in the movie. Knowing what happened there gives you, the crew and the actors, an extra-heightened sense of what you are doing.

Who were your crew? Do you have any thoughts to share about them?

Louisiana offers fantastic tax breaks, and New Orleans has a vibrant filmmaking community, with great equipment and very good technicians – “crews of character” – who I found unique and refreshing. The most important person to me is the first AC, and I was able to bring in Brett Walters. I was fortunate to get Michael McLaughlin as my gaffer, and his team, plus Nick Leon as my key grip, and his team of grips. They are all very experienced and hardworking, and maintained great patience and humour despite the trying conditions. We had two fantastic Steadicam operators. Andy Shuttleworth, an old mate from England who I used to assist in the 1980s, shot the dancing sequences, and the legendary Larry McConkey filmed the one with Paul Giamatti and Solomon at the slave market.

How about your work with other heads of department?

I cannot praise the production design work of Adam Stockhausen highly enough for its simplicity and authenticity. You can only film what is in front of you, and if it’s absolutely spot-on, no matter where you point the camera, it’s going to work. We were also fortunate to have costume designer Patricia Norris, who is a legendary character. She added so much value to the look of the film through the costumes she designed and found. As every cinematographer knows, great audio enhances your images dramatically. The film has a fantastic soundtrack courtesy of the genius of sound recordist Kirk Francis and his team, with a score from the amazing Hans Zimmer.

What was your approach to the camera movement?

The idea was not to limit the camera movement, but to make sure the moves were relevant. The guidance was simplicity. We shot mainly with the camera on the dolly, apart from some specific crane, handheld and Steadicam scenes.

Tell us about any sequences that you are particularly proud of from a cinematographic POV?

There are two dancing sequences when Solomon is playing the fiddle – as a freeman and as a slave – and we wanted to visually join those in the edit. So we shot both of these using the great Steadicam talents of Andy Shuttleworth.

In a sequence at the slave market, we wanted to find a way to highlight the ritualised absurdity and sheer inhumanity of the selling of slaves. Working with Larry McConkey, we carefully choreographed a continuous Steadicam shot around Paul Giamatti and Chiwetel, as Solomon is being sold for the first time. The shot lasts around three minutes, and really heightens the horror of what’s going on.

There is one even longer sequence that I operated on handheld – over eight minutes of continuous filming – for the horrific climax of the film in which Solomon is forced at gunpoint to whip another slave. When I read the script I knew this scene needed to be one uninterrupted shot roaming around the action, and Steve agreed. The effect of the continuous shot in relation to violence is very powerful. If you don’t introduce an edit, the audience does not have an escape and you are forced to watch the images in front of you, heightening the effect of the drama.

I also got to use an amazing bit of kit – the 73’ Chapman Hydrascope telescoping crane arm – on an introductory shot of Solomon and his family walking through Saratoga, NY. The camera moves in a way you’re not expecting, but you would not know the camera was on a crane, and I think it works successfully.

Who handled the dailies?

Although we were shooting on celluloid, you don’t get to see film dailies these days. But we were fortunate to work with Bradley Greer, a gem of a colourist, at Cineworks, a bijou film lab in New Orleans. They took fantastic care over the rushes processing and produced wonderful full-res QT dailies for me, so I had a fairly accurate representation on my calibrated laptop.

Where did you do the DI, and what has it contributed to the movie?

The DI was started at CO3 in NY, with Tom Poole, with whom I did A Place Beyond The Pines. I think he is the best colourist in the US right now. We did a week together in NY, and we then both moved to CO3 in LA to link up with Steve, who had been working on the sound mix, for a second week. The DI is now such an important element of a production. It’s where things come home to roost for the DP as you fine-tune the imagery, and very important to have the right person to help you. Obviously the story takes place over a 12-year period, and Solomon changes imperceptibly during that time. Creating that as a dramatic element came through very careful hair and make-up during the production, but also through a meticulous approach to the DI.

How did 12 Years A Slave challenge you/push your skills?

It’s an epic, period drama about a purely horrible part of history. I think the main challenge for me was to capture the epic scale of the story without losing the intimate and personal point-of-view of Solomon Northrup, whilst maintaining a visual continuity throughout the film – so that it is coherent and compelling from start to finish. But it wasn’t just my challenge. Filmmaking is a team effort, and working with the director, other heads of department, the crew and actors, we have hopefully pulled it off.