Love Life

Darius Khondji AFC / Amour

Love Life

Darius Khondji AFC / Amour

Amour (Love) is the French-language drama written and directed by Austrian director Michael Haneke, winner of the 2009 Palme D’Or for The White Ribbon. Haneke is well-known for his bleak and disturbing style of movie-making, which often document the problems and failures in modern society.

Starring Jean-Louis Trintignant, Emmanuelle Riva and Isabelle Huppert, the narrative of Amour focusses on an elderly couple, Anne and Georges, who are retired music teachers with a daughter who lives abroad. When Anne suffers a stroke, which paralyses her on one side of the body, the couple's bond of love becomes severely tested.

A co-production between companies in Austria, France, and Germany, with an estimated budget of around €15m, Amour won the Palme d'Or at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, putting Haneke in an elite club of seven, with the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, who have won the accolade twice. It has also been selected as Austria’s entry for best foreign language film at the 85th Academy Awards in 2013.

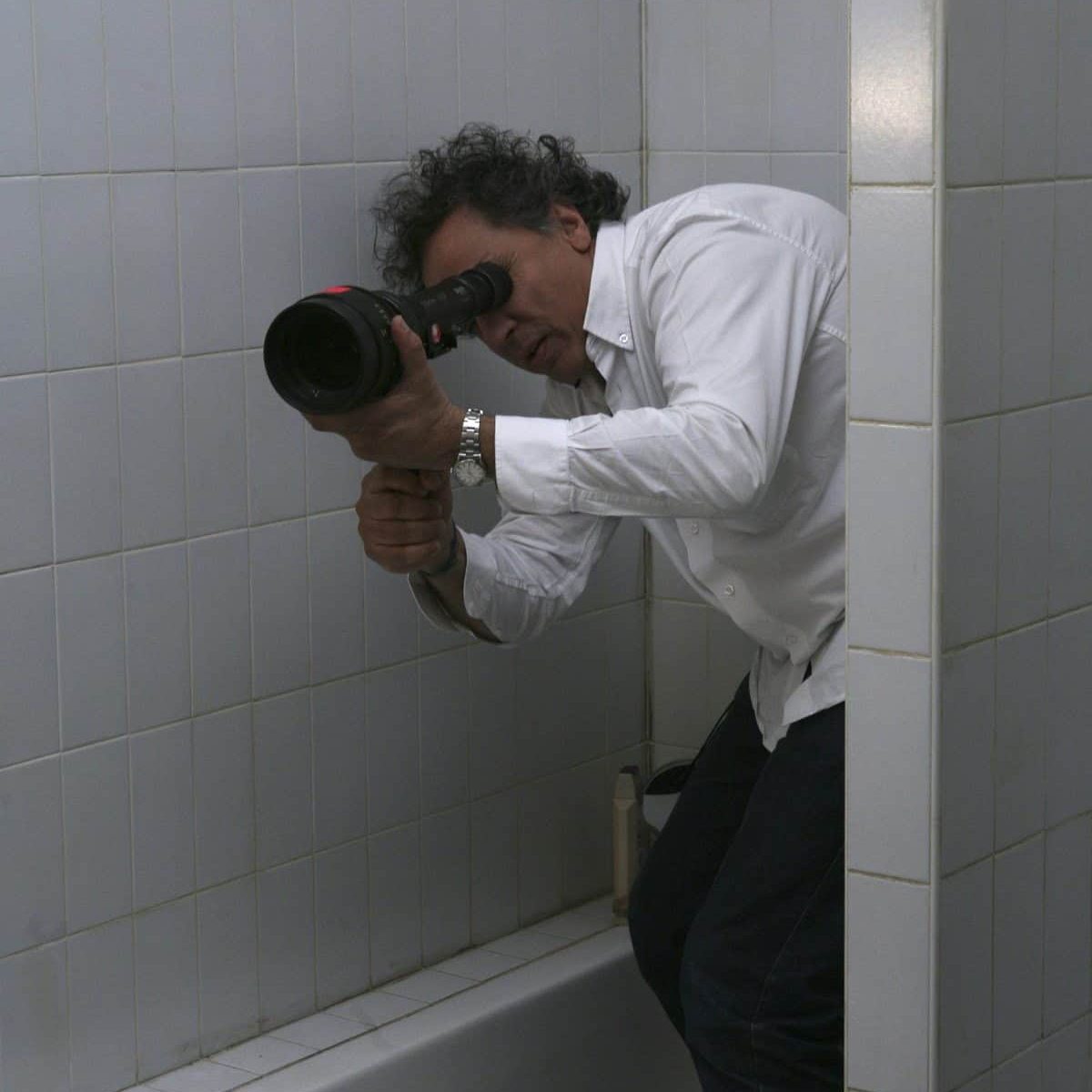

The production was shot by Iranian-French cinematographer Darius Khondji AFC ASC, who majored in film at New York University, and is one of the most celebrated cinematographers of contemporary cinema. Khondji has worked with well-known directors including Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet on Delicatessen (1991) and The City Of Lost Children (1995), and again with Jeunet on Alien Resurrection (1997); David Fincher on Se7ven (1995) and Panic Room (2002); Bernardo Bertolucci on Stealing Beauty (1997); Alan Parker’s Evita (1996); Roman Polanski’s The Ninth Gate (1999); Danny Boyle’s The Beach (2000); Sydney Pollack’s The Interpreter (2005); Wong Kar-wai’s My Blueberry Nights (2007), and Woody Allen’s Midnight In Paris (2011) and To Rome With Love (2012). Khondji was Oscar and BAFTA-nominated for his work on Evita, with César Award nominations for Delicatessen and The City Of Lost Children. He won on the Italian Golden Globe for Stealing Beauty and the Chicago Film Critics’ Association Award for Se7en.

Khondji first met Haneke in New York whilst working on My Blueberry Nights, and shot Funny Games (2007), a disturbing story of two psychopathic young men who take a family hostage in their cabin, for the director

“Michael and I became friends and discovered we have a common taste in music, like opera, and cinema, especially the films of Robert Bresson, such as Au Hasard Balthasar (1996),” says Khondji. “He talked to me about Amour at that time. I loved the idea of creating an intimate recording, spanning the course of a year in lives of this elderly couple. He’s not a director who wants to make anything pretty for the sake of it, and it was very different to recent stylised genre films I have worked on.”

Khondji had eight weeks prep on the production. Principal photography took place on sets built at Éclair Studios at Épinay-sur-Seine, from February to April 2011, with the cast and crew working five-day weeks.

Among the crew were A-camera/Steadicam operator Jorg Widmer, noted for his work Terrence Malick’s last four features, including Tree Of Life, Julien Andreetti as focus puller, Vincent Scotet the 2nd AC, gaffer Thierry Beaucheron and key grip Cyril Kunholz. “They are all superb technicians,” notes Khondji. “I had just worked on Midnight In Paris with this crew, and only wanted to work with them again after that. They have a kindred spirit and gave their best on every shot.”

Khondji says he did not undertake any particular visual research, in terms of films or painters, for Amour, but did listen to Schubert and Beethoven during prep. “It was more a spiritual research, and how to tell this story, to record it, in an honest way. Filmmaking is about creating a mood. That mood, or look, must be very close to the director's soul. Michael is an extraordinary director who takes us where he wants with the precision of great surgeon, or an orchestra leader. Following him sometimes feels like you are a musician, a violin maybe, in the middle of amazing orchestra.”

Indeed, Haneke’s precision meant Khondji and Widmer strictly followed sketched storyboards, and even a computer-generated pre-visualisation, of the film created by the director. This meticulousness was such that even the parquet flooring in the apartment, where the film is largely set, was sanded completely flat, and then rigorously tested with the camera and different lenses on the dolly, to ensure completely smooth camera moves.

“This is radically different from the freeform work that I have done with Won Kar-wai or Woody Allen,” admits Khondji. “With Michael everything is precise. It’s different, but it’s a wonderful way to work. Although he takes advice, Michael has a gut feeling about how his film needs to be shot. He approaches filmmaking like a conceptual artist, as well as a director. If there were any variances to the storyboards, it was mainly to accommodate the actors’ needs.”

"We also used a lot of Lekos bounced in some areas of the set and mainly practical lights to illuminate the set by themselves."

- Darius Khondji AFC

Khondji harnessed the ARRI Alexa, with 35mm Master Prime and 40mm and 50mm Cooke S4 and S5 lenses, supplied by TSF rental company in Paris. The production is one of the first movies to shoot ARRIRAW to Codex Digital recorders, with dailies processing and transfers completed through Digimage in Paris.

“The combination of the dynamic range of the Alexa’s sensor and shooting ARRIRAW enabled us to capture a lot of the production using practicals, and the overall look is more luminous as compared to celluloid,” he says. “Shooting ARRIRAW also gave me the feeling that I was exposing a film negative.”

The apartment sets were based on Haneke’s grandmother’s apartment in Vienna, and emulated the designs on Parisian civil architect Georges Haussmann. Crucially, this setting was positioned with a southern aspect, with sunrise, day, sunset and nighttime in mind. Haneke only wanted sunlight to enter the kitchen, with the other rooms – bath, living and bedroom areas – being lit by reflected or bounced light.

“Michael was absolutely scrupulous about the change of light, the passing of the days and the seasons, and how sunlight should penetrate the apartment, and we shot almost the whole movie in in chronological order. We used mainly 20Ks through the windows, and spacelights or daylight ambiance in the apartment. We also used a lot of Lekos bounced in some areas of the set and mainly practical lights to illuminate the set by themselves. My chief concern was with the actors, and how not to make things too painful or complicated for them. I was also concerned with the lighting continuity. When you make a realistic story, a film shot at close quarters in a Parisian apartment, that takes place over the period of few months with the change of seasons and change of light during a day, then you always worry about continuity, and whether the changes you make really serve the story and the characters. This creature, the mood of the film, has to be alive and move with the story and the characters.”

When asked if there were any happy accidents during production, Khondji replies, “There are no accidents in the shooting of a Michael Haneke production. Amour is a poignant film. I am very proud to have worked on it, but I’m even more proud of the story it tells.”