Greg Bushell on shooting documentary short Safe Light

Mar 4, 2025

After striking up a friendship with Ukrainian photographer Vic Bákin online, London-based visual artist Greg Bushell travelled to Kyiv to document how the full-scale invasion has affected his daily practice. The resulting work explores how Bákin uses photography to confront his unprocessed experience of a new wartime reality.

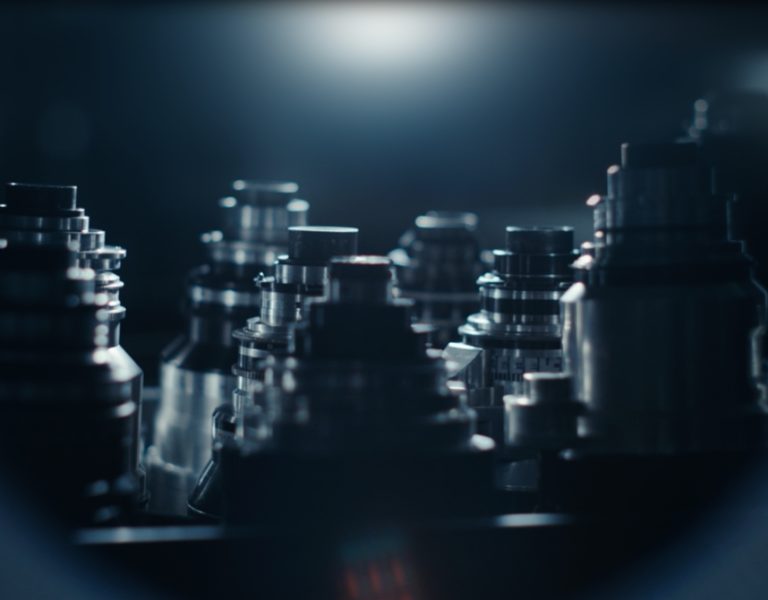

Following the attack, Bákin found refuge in the warm embrace of the red lamp of his makeshift darkroom. Safe Light captures how Bákin’s exploration of the “coming-of-age” of Ukrainian youth and queer subcultures has undergone an evolution in recent years, with many of Bákin’s subjects now enlisted in the war. Despite efforts to avoid overt political labels, Bákin’s work shoulders the heavy weight of its context. Speaking of the full-scale invasion in 2022, Bákin says “Printing and counting seconds in the dark became a meditation for me, [a] kind of mental therapy.”

Safe Light is shot on 16mm and Super-8 film, mirroring Bákin’s preference for the tactile imperfections of the analog format. The score is made up of Ukrainian artists – Bryozone, Polje, Yuri Lugovskoy and iconic ethno-gothic rock band, Cukor Bila Smert (Sugar White Death).

What cameras and lenses did you choose for this project and what influenced your decision in selecting them?

As I was working independently, my kit was informed by what I had available. But working with limited resources had relevance. My photographer subject, Vic Bákin, and the aesthetic of his “Epitome” series was influenced by the necessity of his situation; given all the photoshops in Kyiv closed at the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he had to re-use his photochemicals until they were exhausted. But the results are powerful. That same DIY mindset shaped the way I approached this project. By embracing this guerilla “back-to-basics” mantra, I was able to take advantage of these challenges and really enjoy the pure fundamentals of filmmaking.

I shot most of the film on an Arriflex 16st. I bought it from a stills photography shop for a fraction of its value. I also purchased a radio-controlled car battery and created the right connection point with some pliers to power it. I have to thank Danill Nevskij who serviced the camera for free in support of the project. I knew that I couldn’t easily travel to Ukraine with 400ft magazines so I picked up a Bolex H16 Rex-5 too. This allowed me to increase the speed at which I shot. We also shot bits on Vic’s Nizo Braun super-8 camera, adding another texture to the film.

Call it amateurish, but I loved the idea of not going overboard. The filmmaking was stripped-down and without this obsession for eye-wateringly expensive gear.

Can you describe the lighting setup for the film and how the choice of lenses and lighting sources contributed to the overall mood and aesthetic?

Most of the film revolved around the light of a red safelight lamp, which acted as Vic’s sanctuary away from the chaos outside the walls of his bathroom. Red is associated with danger but I wanted to subvert our prior associations with this colour and present it as a marker of safety, a womb-like comfort. For some shots we were able to shoot in the conditions of a single photographic dark room lamp but there were a couple of instances when we needed to boost the light levels with an LED spot. I didn’t have a Barry Lyndon lens.

The lenses I used were the Schneider Kreuznach 16mm (f/1.9) and 25mm(f/1.4) Xenons and the Angenieux 5.9mm f/1.8 for the Arriflex. And the Angenieux Zoom 17-68mm f/2.2 for the Bolex. The flexibility of the 3-lens turret on the Arriflex was great – it took me back to 1950s reporting.

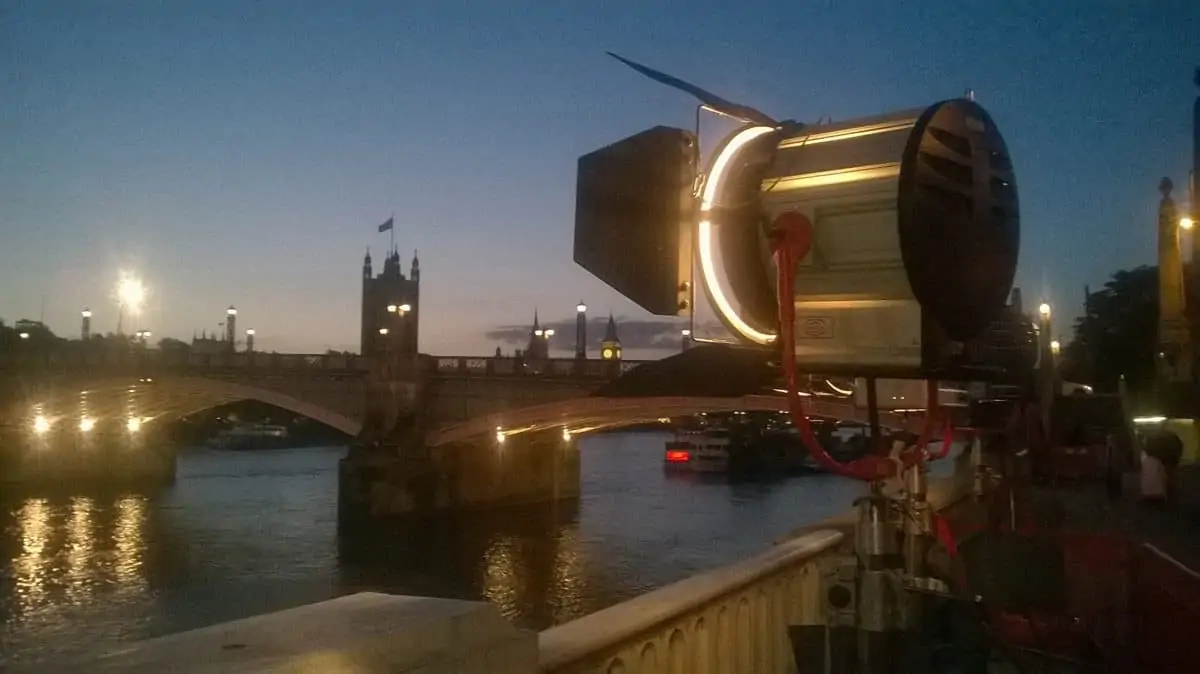

All the exteriors were shot in natural light. When I came up with the idea, Vic’s stark, uncanny imagery was my main reference point. I travelled at the start of Spring of 2024, and was caught by the surprise of a sunny Kyiv. Often, the subject matter of war is portrayed with a gloomy look. But the whole experience of travelling there was about subverting our preconceptions as an outsider looking in. In fact, the warm, picturesque imagery helped to imbue some hope into the film as well as convey the complexity of the situation. The film opens on a devastated bridge in Irpin. Seeing the warm sun reflecting off the calm, soothing water hits you with a sense of discomfort: the tranquil aftermath of horror.

Was there a particular camera movement or rig that you found essential to achieve the desired aesthetic or narrative impact in your shots?

Again, camera movement was informed by practical limitations. There’s a shot where we glide over a collection of Vic’s prints. All we had was a stills tripod with a pivot at the head. So I counterbalanced the arm with a tote bag and slowly swung it in a circular motion to give the feeling of an ethereal eye passing over.

While there are moments of dynamism in the film, I mainly wanted to shoot a lot of stable shots. Motion could be felt in what moved in front of the camera, not by the camera itself. I didn’t want to try to manipulate the audience with trickery all the time. It also felt very appropriate for Vic’s quiet, reflective images.

But, sometimes, we weren’t afforded the luxury of a tripod. When walking around St. Sophia Cathedral, I was warned we’d be branded as a “professional” shoot if we used a tripod so I had to go handheld. In the final shot of the film, you see Vic climbing a hill in Kyiv’s Hryshko National Botanical Garden. With no tripod to hand, we propped up a rusty bit of metal to achieve a stable shot.

Did you face any technical challenges with the lighting or camera gear during production and how did you overcome them to maintain the visual integrity of the film?

I chose to shoot on film to mirror Vic’s analog method for his “Epitome” series. After all, the film is all about the darkroom process. But the decision to shoot on film had its challenges.

The first being taking an x-ray sensitive medium in and out of a warzone. I was very scared that my luggage and packages would have to go through intense inspection. The risk involved of pouring all of mine and my subject’s time and energy into this project for it to come out overexposed gave me a lot to think about. There was a little suspicion of my archaic Arriflex at the borders but mostly it was fine.

That being said, I don’t want to overdramatise my journey to Ukraine. Travelling via train through Poland is a very normalised part of many Ukrainian’s lives now, the ones that are able to leave and return to the country. Most men of fighting age are not allowed to do so.

Another challenge I faced was being on the road and changing my 100ft reels by myself. With the assistance of an incredible group of friends that guided me, I travelled to sites of Russian war crimes – Borodyanka, Irpin, Bucha. I didn’t always have the chance to change reels and shoot in the correctly balanced film. There is a sequence that made it into the film where we glimpse at some of the devastation around the Kyiv region. Out of necessity, I shot 500T in daylight. I decided not to “correct” this in post-production as it felt like it illustrated this journey into the void.

How did you approach colour temperature and lighting ratios to create contrast and texture in the scenes and were there any specific lighting instruments, like HMIs, LEDs, or traditional tungsten lights, that you used?

Shooting a lot with natural light meant carefully timing each shot. One of the shots I wanted to get was of the sun pouring in across a wall that had been covered with Vic’s palm-size dark room prints. As our location wasn’t rich with sunlight, I had a window of about 15 minutes to get all the shots before the sun would hide behind a neighbouring building. If you want to be technical, I wanted a 4:1 lighting ratio to give my subject separation from the background.

But, while I tried to meter everything and keep an intentional lighting ratio, I had to leave a lot to intuition. There’s a shot in the film where we view Vic’s reflection through the agitated red chemicals with a contrasty lighting ratio – maybe 8:1. We shot 500T to give it that deep monochromatic red. But we would shoot some of the darkroom scenes late into the night and didn’t have the luxury of being technical all the time – quite often we’d wrap at 23:55 and I’d have to rush back to my apartment before the midnight curfew.

In terms of post-production, how did your choices of camera and lighting affect the colour grading process?

Shooting on film with natural light or a monochromatic red gave us a solid foundation for post-production. A couple of my references were shots of Audrey Hepburn in Stanley Donen’s Funny Face (1957) and the painting/photography of William Klein. You have these extremes of vivid reds and at the same time a (completely) desaturated image in the composition. In this scenario, I love the look of strong, vacuous blacks – think Gunnar Fisher for The Seventh Seal (1957) which historically I think was achieved through using strong light, low ASA film stock and then stopping down.

When we leave the stylised, dream-like space of the dark room, I wanted to use a naturalistic look. I was inspired by Agnes Varda’s One Sings the Other Doesn’t (1977) and its desaturated colour palette.

How did you collaborate with the director/DP to ensure that the visual language of the film aligned with the narrative tone and did any specific equipment choices help facilitate that vision?

As I shot this on my own, there wasn’t a director/DP relationship. But, given my subject is a photographer, there was a lot of communication between myself and Vic on the visual language of the film.

In terms of specific equipment, I experimented with different materials to diffuse the lens. I taped a chemistry diopter (one you’d find in a secondary school science classroom to explain refraction) onto one lens. It gave the POV of Vic looking through his small eye-piece at his negatives on the lightbox.

I used other warped pieces of glass, slowly moving across the lens. This gave the impression of a print being submerged in water while also giving it a surrealist tone.

I think this was the first project where I stopped caring about kit and, looking back, I truly loved it. I allowed the parameters of my journey to Ukraine to inform the look and feel of the film.