HOME FROM HOME

Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle ASC BSC DFF had early dreams of a career in real estate, which shaped his visionary approach to filmmaking, blending imagination with reality.

“From a young age, I thought I was going to be an estate agent,” says Anthony Dod Mantle ASC BSC DFF. It’s not the answer you expect from a key architect of the avant-garde Dogme 95 movement.

Yet the more this experimental and intuitive filmmaker reflects on his creative DNA, the more he realises how foundational was a childhood growing up in a succession of different places.

Dod Mantle’s father was in the Navy during the Second World War, but it wasn’t continued military service that prompted continuous upheaval. Indeed, his upbringing in the mid-fifties was avowedly middle class and untroubled, save for being blighted by various bronchial and sinus-related illnesses.

“I was very allergic and asthmatic to just about everything on the Earth,” he says. “Each diagnosis prescribed our family move me from one place to another where the air was better.”

From Oxford and the Thames Valley to Cambridge, the Dod Mantle family moved multiple times to flatter, rural land, which ultimately did help Anthony recover.

“By which time I’d seen so many houses that my intellect was working subconsciously to imagine what life would be like with my mum, brother, and sister in each empty space, often lit only by the light from a window.”

He completes the analogy. “I spent my young days in all these rooms, which are really like studio spaces. Making films, you walk into spaces with nothing but your imagination, and then you try to design it together with clever people, and it becomes a world that then becomes a film.”

It’s fair to say that his imagination was also fired by his mother, who painted, sketched, and drew throughout her life. But Dod Mantle was unaware of wanting to communicate in images until he was 24 years old. By then, he was living in Denmark, having pursued a love there, and working in a furniture factory.

Intrigued by a chance find of a second-hand stills camera, he began evening courses in black-and-white photography. He spent 1976, his twenty-fifth year, in India retracing his colonial forefathers and “taking thousands of images of grotesque poverty, kids on the street”, he says. “The degree of begging and suffering was extraordinary to me as a middle-class Cambridge kid with a couple of telephoto lenses. It made me question the ethics of what I was doing.”

In London, taking a degree in visual communications, his mentor said something that resonated. “Whatever I was pointing the camera at, however strange or exotic, is always about me,” he said. “It’s about yourself.”

Having retained some Danish from his earlier sojourn in Copenhagen, the 28-year-old was next accepted into Den Danske Filmskole, where he learnt the more “scientific, mathematical, and technical” side of cinematography.

“I was learning why I wanted to take pictures, but because I thought that the life of the stills photographer was a very lonely one, I became attracted to the idea of filmmaking, where you travel with a crew as if with a family.”

At 34, he may have graduated from film school a little older than many contemporaries, but with a maturity of life experience that earned him an edge shooting documentaries.

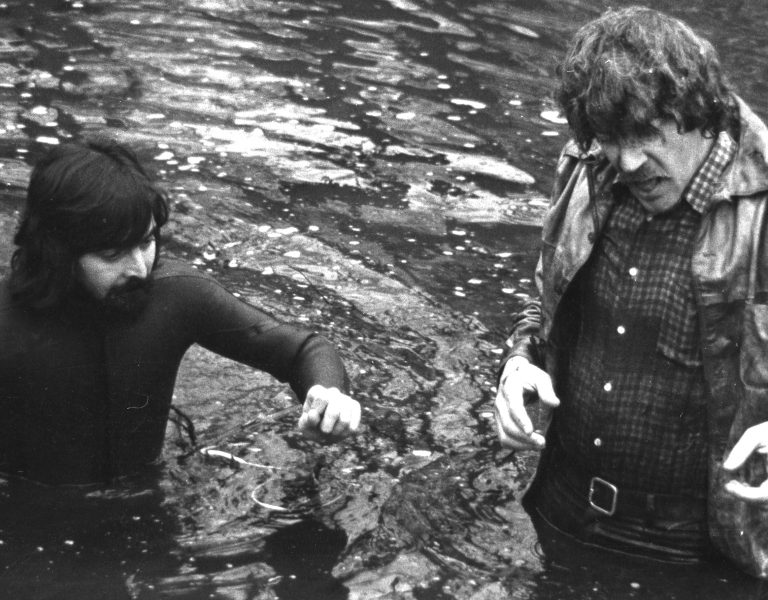

“I was getting known in Scandinavia for making quite artistic-looking feature docs,” he says. “I learned an awful lot about filmmaking with very few tools and small crews. You learn how to be strong, physically and mentally, and quick with what you have to create stories. I was interested in breaking from the more obvious documentary style of filmmaking and putting more poetry and lateral thinking into the documentary tradition. From there, it seemed natural to work in fiction.”

At film school, he hung out with students in the year above him, notably writer-director Susanna Bier (with whom he worked on HBO drama The Undoing, 2020) and Peter Aalbæk Jensen, the founder of Danish film company Zentropa and frequent collaborator of director Lars von Trier.

It was the Jensen-produced, low-budget road movie De Største Helte (1996) that cemented the cinematographer’s relationship with director Thomas Vinterberg. Festen (The Celebration) in 1998, the first feature film made with stripped-back Dogme 95 rules, put Dod Mantle on the map.

“Despite the 15 years between us, we are very close friends, like brothers,” the DP says. “He became a very big part of my development in film. There were brilliant and awkward sides, as there are in any DP-director relationships when you’re so intensely committed, but Thomas and his films have so much humanity, I love working with him.”

Von Trier, with whom he made Dogville, Manderlay, and Antichrist, was another “very important cog in my own development. He is this force. An original thinker with extraordinary artistic capabilities.”

Unique perspective

Dod Mantle calls himself “a freak from Britain” with “sloppy cabbage Danish” during his time at film school but recognises that being an outsider “made me slightly different” from peers.

“For better and worse, I approach things with different eyes. When I return to the UK, I return as a European, seeing my own country with different eyes.”

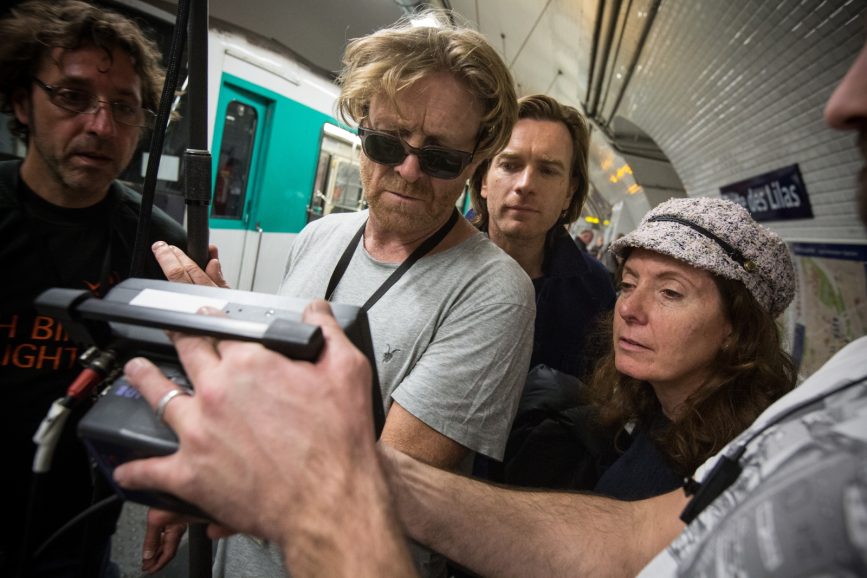

In Danny Boyle, he found another kindred spirit. Boyle had seen Festen and wanted to work with the DP. They did, first on a couple of TV movies in 2001, “and then we were shutting down the M1” on 28 Days Later (2002).

Twenty-two years later, and they are back shooting 28 Years Later, one of only two films in Dod Mantle’s CV that can be classified as sequel or franchise. The other is T2: Trainspotting, also for Boyle, with whom he also made Millions, 127 Hours, Trance, the TV series Pistol, and won the 2009 BAFTA and Oscar for Slumdog Millionaire.

“Danny, Andrew [McDonald, producer], and Alex [Garland, writer] are family and important people to me in my life. 28 Years Later is equally as anarchic and challenging as I was feeling on 28 Days. They’ve both been hard films to make because we don’t want to get complacent, sloppy, or lazy, so we always try to push. I don’t want to repeat myself, and that’s important. Danny and I have that in common.”

“I’m still my own worst enemy,” he insists. “Believe it or not, when I take images, I like few of them enough. I want to do better all the time.”

He says he has been offered several Marvel projects, but not one has piqued his fascination sufficiently. “I don’t say ‘no’ because it’s Marvel. I just look at the essence of the words on the paper, and I think very critically about the relationship between the director, the writer, and the producers, and see if there’s a parallel energy and attitude that I feel comfortable with. That might draw me to a well-established Hollywood director like Ron Howard (Rush, In the Heart of the Sea), or it could be a penguin swimming 5,000 km in the wrong direction (subject of 2024 feature My Penguin Friend). To me, the balance is important because I’ve been on a couple of projects where the nucleus of the film has not been in harmony.”

In the harmony camp, we can list work with Harmony Korine (Julien Donkey-Boy), Angelina Jolie (First They Killed My Father), Kevin Macdonald (The Last King of Scotland), and Oliver Stone (Snowden).

Feeling the frame

As a child of European indie cinema, operating came naturally to him. “There are DPs, especially coming out of documentaries, who have only ever had the camera with them, feeling it as part of their body. For me, operating is not about seeing. It’s feeling. I believe I feel before I see.”

“The bottom line is that any filmmaking tool has to be as close to being an extension of my emotional self as possible. That’s why I tend to work small. If I go big, I still want to be somehow agile.”

He sometimes consciously shuts either his right or left eye and views the scene using just one eye “because of the different emotions it creates in my brain,” he says. “It causes me to do irrational things in operating. I’m organic like that.”

Understandably, on larger shows with more complex equipment, this instinct can get lost. “If I’m on the floor watching a monitor of a camera on a crane with five other people talking on walkie-talkies, it’s no disrespect to anybody, but the delay between the thought and the actual movement is pure pain, anger, and frustration. I like to be instantaneous. I want to feel the story in my backbone, in my body, and soul.

“So even if I am watching a Technocrane, I want to feel I am operating it because it’s my responsibility. If I don’t feel it first, then the shot is dead before you’ve even pressed a button.”

It’s a process that he traces back to those days imagining life in new rooms. “I dream pictures before I make them. I sometimes anticipate the spaces years before I suddenly find myself creating them with other people. The real DPs—the ones who are kind of masters of originality—they think a lot more invisibly than you can imagine, way before the thing is made.”

Operating the camera also means being close to performance, as he is with Jodie Comer, star of 28 Years Later. “Some people have this extraordinary combination of aura and bone structure and she just has that. This film is partly driven by the rules of the [zombie] genre but there’s also a humanity which is evoked by actors like her.”

One wonders what if felt like spending hours photographing president Putin for Oliver Stone’s four-hour documentary The Putin Interviews (with Rodrigo Prieto ASC AMC) between 2015-17.

“You’re looking at the eyeballs, you smell his breath. You look at the size of his feet. The smell of his cologne,” he says.

“I told him that my father had been saved from drowning twice by the Russian navy. Had they not fished out of the water twice, I said, I wouldn’t even be standing here.

“Then he took me into the back of the Kremlin, right past the cucumber sandwiches and the ladies doing the tea and showed me this portrait hanging on the wall of his own father. Their eyes are very similar.

“It was like having a chat to an actor between takes. You suddenly sense that the performance is switched off, the uniform had come down.

“It was a deeply odd and uncomfortable moment. There were other moments, but this was the most memorable. Everything about his politics, conquering the world or killing people, and me making films, is completely different but in this moment, we were bound together by something.

“It was a very strange, very intimate experience but it actually illustrates the extraordinarily beautiful and precious privilege we have doing the job we do.”