So spring arrives with Oppenheimer having finished its winter-long Sherman’s March – with nuclear fission standing in for fire – through award season, as it kept racking up wins from one guild to the next, all the way through the BAFTAs, to Oscar night.

In our December column, having just come back from the Hollywood Professional Association (HPA)’s own award gathering, which serves as a kind of “pre-season” event before nominations kick in, even there the story of the soul-wracked scientist who helped beat Hitler to the bomb, won the evening’s top prizes for both its colour grading and editing, which felt, we wrote, “like a bit of an augury heading into award season proper”.

And so it was. It had been thought, back around Barbenheimer weekend and the apparent revival of movie-going (or at least, going to tentpoles with savvy marketing campaigns – the jury is still out on the theatrical future of midsized films), that the two main Oscar competitors were set, perhaps to be joined by Killers of the Flower Moon, come autumn. Though as it turned out, even some of those midsized movies, through word of mouth, and shorter windows to streaming and VOD – like American Fiction, Anatomy of a Fall, The Holdovers, and Zone of Interest – all found audiences too, and at least a bit of Oscar gold.

Some of that gold even appeared to come at Oppenheimer’s expense, particularly in the sound and adapted screenplay categories, where, respectively, American Fiction and Zone of Interest won awards (as they both had at the BAFTAs, and also making Zone the first British film to win for Best International Feature).

The diversification of craft awards included wins for Poor Things, as Bella Baxter continued to steal Barbie’s thunder for the “becoming self-actualised in a patriarchy” movie slot (for which, apparently, there can only be one major contender at a time). Those wins came not only in the Best Actress category (a genuinely moved Emma Stone appeared backstage saying “oh, God. I think I blacked out. Yes, I was very shocked. I still feel like I’m – I’m spinning a little bit. So, yes, it was – it’s a huge honour, and I’m very – yes, I’m very surprised.”), but for Production Design, Makeup, and Costume, as well.

Winning designer Holly Waddington talked about using costumes “to tell the story of (Bella’s) development. It was just a constant challenge for me,” describing the process “like a jigsaw puzzle because you have to move so rapidly through different stages”.

That’s a counter-rhythm to the slowly-building horrors that Zone of Interest accrues. We asked its winning sound team of Tarn Willers and Johnnie Burn about earlier statements that the film was constructed to rely as much on its sounds as its visuals – i.e. the “aural” part being where the increasing horror comes from, as audiences realise how much the Höss family is both deliberately shutting out – and complicit in – what’s happening just over their garden wall in Auschwitz.

How did they approach the task with historical reverence to the victims, while creating “this kind of awful yet compelling re-creation”?

To which Burn agreed that per his understanding with director Jonathan Glazer, the film would be “pivotally working on how the sound design brought the narrative… (but) reading the witness testimony and understanding how to translate that period in time when there is no archival footage of audio recordings or anything […] yeah, that was the challenge. And as you say, treating it respectfully was immensely important.”

Music for the soul

On the other end of the spectrum, another film dealing with sound – in this case, music, and how the playing of it heals, and thus, how important it is to put the implements of that playing into the hands of budding musicians – won for Best Documentary Short. This would be The Last Repair Shop, which represented a very local Oscar win. Not in the usual Hollywood sense pertaining to the Oscars themselves, but because that repair shop is part of the L.A. Unified School District (LAUSD), and its small staff – each with moving stories of their own – keeps those freely given school instruments working, so the school music programmes can play on.

Additionally, the film was picked up by the newish LA Times Studios, started by the paper of record here (even if by “paper”, we increasingly mean “digits”), and made freely available on YouTube. So it’s had a very wide viewership, locally and beyond.

A couple days ahead of the ceremony, we swapped emails with that film’s DP, David Feeney-Mosier, who told us that one of the film’s two directors, Ben Proudfoot (himself a previous Oscar winner in this same category, who co-directed here with LA Unified-trained pianist and composer Kris Bowers) “had seen a short doc I shot called Jim Svejda: Between the Notes [Svejda being a legendary, and now retired, classical music deejay of many decades standing in L.A.]. He apparently liked what he saw, and reached out to me about a new project he was working on.”

They began that project in 2019, just ahead of the pandemic, but for his part, Feeney-Mosier says he doesn’t “work all that much in documentaries, but I was attracted to the more intentional, narrative style that we discussed utilising for the film. I find it a fun, sort of hybrid, approach. I also found the subject matter very compelling… and was certainly amazed that a small team of less than a dozen technicians repaired something like 80,000 instruments a year.”

It was shot “on an Alexa Mini with Cooke Anamorphics” to give the film “a slightly elevated and composed feel, still naturalistic but just a degree removed from reality… (while) the wider aspect ratio also meant we could see more of the shop, feel more of the instruments on the periphery.” The small film is also having a wide impact, certainly locally, though other school districts are now contacting LAUSD about starting similar programmes of their own. “I found,” Feeney-Mosier said, “the human connection between the service of repairing instruments and the students who cherish music to be a very powerful theme. The film is incredibly optimistic in that respect.”

Which, of course, is another aspect that makes it opposite to Zone of Interest, which reminds you, really, how prosaically the horrors of the world can start, developing their own intractable rhythms.

Oppenheimer resides somewhere on that scale as well, particularly with its cautionary concluding scene, about which, backstage holding his directing and producing Oscars, Christopher Nolan said that while “the film ends on what I consider a dramatically necessary moment of despair, in reality I don’t think despair is the answer to the nuclear question,” going on to advocate “working to pressure politicians and leaders to reduce the number of nuclear weapons on our planet and make the world safer”.

And as Academy evening wore on, Nolan’s cautionary opus regained the momentum, not only with its acting and directing wins, but those for editing and score, as well. And, of course, for Hoyte van Hoytema ASC FSF NSC’s cinematography, which was his first Oscar win after an earlier nomination for Nolan’s Dunkirk.

After congratulating him backstage, we asked whether now, after several collaborations with the director, they’d developed a shorthand with each other, a streamlined way of communicating, as they approached new projects?

With shooting on film already a given, Van Hoytema said the other “given is that we always want to build new things and invent new things in order to get shots that we’ve never seen before… sort of push the boundaries of what we are trying to pioneer a little bit with the big format camera and the film, (yet) keeping the camera very flexible and moveable,” adding that “once you are working with a lot of technology and equipment on set, to make sure that things can also (be) very intuitive. Because, you know, in the end, you are dealing with human emotions.”

Including that of gratitude. A week earlier, at the ASC awards, Oppenheimer had also prevailed. Van Hoytema said then that he’d had a “very vague, and very, very long speech” prepared, but instead was going to just “take a breath”. After which, he proceeded to thank his entire camera crew, most of whom were sharing a table with him. The list not only started with his 1st AC, Keith B. Davis, but even took in Dan Sasaki, Panavision’s storied senior VP of Optical Engineering, who designed some special IMAX lenses for the film, particularly its “subatomic” sequences.

Realising dreams

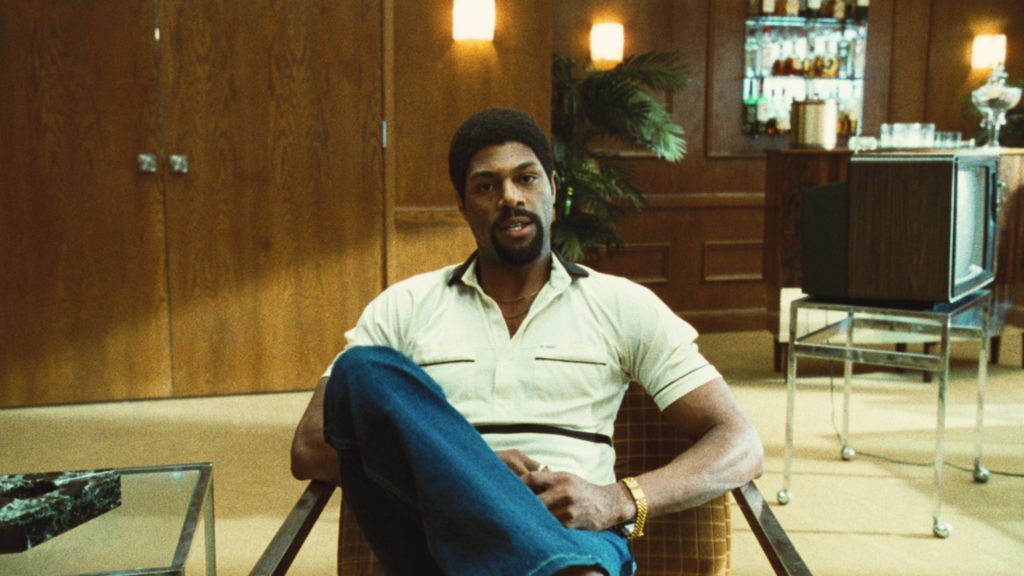

The event was held at the Beverly Hilton Hotel, where so many award season gatherings take place, from the Golden Globes onward, and in its vast and sparkly ballroom, we found ourselves seated with a few of the evening’s nominees, including Ricardo Diaz, who was up in the hour long episodic category, for HBO’s Winning Time, the story of the ‘80s-era Kareem-and-Magic Lakers teams.

We’d actually talked with Diaz during last year’s strikes, when he had some fairly unvarnished things to say about the necessity of the walkouts, vis-a-vis a “now or never” sense of film workers falling ever more behind, in terms of wages and working conditions, and whether IATSE had missed out on its chance to wrangle from studios similar concessions to those that actors and writers eventually won.

Negotiations for IATSE’s current contract are underway as we write this, by the way – the time does indeed fly – and we’ll have more in future columns on how it’s all going. Or not.

As for the ASC nomination, Diaz said earlier that it “means the world to me. My cousin – a true cinephile – gave me my first issues of American Cinematographer right before I graduated high school. When I read it, I felt like a door that was previously locked had been blown wide open… It was also the first time I became aware of the ASC Awards. I remember seeing a roundup of the film nominees, and it always stuck with me how incredible it must feel to be honoured by your peers.”

Now, years later, Diaz was happy “being in a room full of my heroes, past and present”.

And though that category eventually went to the estimable M. David Mullen ASC, chalking up another win for the visually rich finale of the Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Diaz thought that his episode, “The Second Coming”, helmed by DP-turned-director Todd Banhazl ASC, “had wonderful pathos” in exploring the tragic past of Celtics’ forward, and constant Laker rival Larry Bird, giving them “an opportunity to create a new visual language that would be different from previously set looks on the show. That new language, married with an excellent script, helped our episode stand out.”

Among the other standouts and honourees that evening was Amy Vincent ASC, there to accept a President’s Award. We’ll have excerpts from a longer, post-award chat with her, next column out, but in telling of her own journey, she reminded us that she was “the sixth woman to be invited to the ASC” and how she stood on the shoulders of those who preceded her (and who were there, shoulders and all, such as Nancy Schreiber ASC and Ellen Kuras ASC).

“We all stand with each other,” she said, mentioning a whole cohort who got in around the time she did, luminaries like last year’s ASC winner Mandy Walker AM ASC ACS, along with Reed Morano ASC, Natasha Braier ASC ADF, Tami Reiker ASC, Polly Morgan ASC BSC and others.

“There’s a sisterhood that we have,” she said, and they “welcome the new folks with open arms,” adding that “we can’t wait ‘til Natalie Kingston gets a couple things under her belt,” referring to the Emmy-winning DP for the Apple TV+ series Black Bird.

Of those earlier days, “it was a very different time in the world, a different time for women,” she says, adding her own wish that “the next generations coming forward will be able to (simply) focus on the beauty of filmmaking, as the representation will hopefully be endemic by then.”

Other honours went to Steven Fierberg ASC, for Career Achievement in Television, with a Lifetime Achievement Award to Don Burgess ASC, who was introduced by his own long-time collaborator, Robert Zemeckis, for whom he shot Forrest Gump and numerous other films, along with a Spotlight Award to Australia’s Warwick Thornton ACS for The New Boy, which he also wrote and directed. There was also a Board of Governors Award to Spike Lee, there with his early career DP-collaborator Ernest Dickerson ASC – who later became a director himself – as Lee noted that “without cinematographers, we ain’t got shit.”

Ace editors

And as memorable, and in some ways, intimate – despite its renowned setting – as this year’s ASC awards were, they were the capper to a fullish awards day that had begun earlier with a brunch-time gathering of those ace editors at ACE – the American Cinema Editors – passing out their annual Eddie awards.

Oppenheimer’s editor Jennifer Lame ACE prevailed there too – as she would on Oscar night – but in fairness, since they, like the Globes, also have a comedy division, so too did The Holdovers, and Kevin Tent ACE.

But the real pleasure of the midday gathering came with its honorary awards, with George Lucas’ anecdote-laden introduction to legendary film and sound editor Walter Murch ACE, there to receive one of the afternoon’s two Career Achievement awards (the other going to documentary editor Kate Amend ACE) which no one minded because the anecdotage was along the lines of how he, Murch, and so many others who would come to define “’70s cinema” all met and started working with each other, as film students, with Lucas recounting how he later advised Francis Ford Coppola that he’d better say “yes” to directing that gangster book adaptation that Paramount was offering, because they needed the money for their more indie-minded projects there at American Zoetrope.

Murch would eventually be Oscar nominated for editing the filmed sequel to that book, Godfather Part II.

There was also Kevin Smith’s hilarious introduction to the equally hilarious, and droll, John Waters, who was there to receive ACE’s Golden Eddie, which recognises “an artist for their distinguished achievement in film”.

In this case, films that could often be described as “one of those f***in’ movies!” as Smith’s father once did, after taking his family to see Waters’ Polyester, where the budding filmmaker had hoped to experience “Odorama” for the first time. But alas, the drive-in, which his father exited early, was without the requisite “scratch ‘n’ sniff” cards.

Still, it left the young Smith knowing exactly what kinds of films he wanted to make, when he grew up – movies like “those”!

All of it serving to remind one of what seemed so compelling about visual storytelling in the first place, even when you can barely imagine a future in it – like Diaz reading American Cinematographer in high school, or like this correspondent did, years earlier, in college, in his campus video production offices, compelled by the work that Lucas and his ‘70s-era cohort – Murch, Waters, and all the rest – were turning out.

A week later, as award season wrapped, and Nolan stood backstage with his wife and co-producer, Emma Thomas, and producer Charles Roven, after their Best Picture win, there were already questions about memories, and what might be consigned to them, as the trio was asked when the project truly became “real” for them. Nolan talked about early makeup tests – Cillian Murphy in his Oppenheimer hat, and Emily Blunt with her “old-age makeup”. They shot them “on the very first black-and-white IMAX film that had ever been made, and we projected it on an IMAX screen over at the Citywalk at Universal,” he said. “That was a very special moment, special to realise what the actors were going to do, and that the thing was going to work, and to see that technical side of things that Hoyte was bringing to the table with photography. It was remarkable and that will always stay with me.”

Just as the resultant film stayed with those movie-making peers who vote on each season’s awards, and the audiences who have flocked to see it since.

Meanwhile, we shift from awards mode back to our Across the Pond mantle starting next month, but even without awaiting “the envelope please,” there will still be plenty of surprise and revelation in the weeks ahead. We’ll see you then.

@Tricksterink / AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com