Jester, lensed by Bart Bazaz, is a 17th-century period piece imbued with a sense of scale and adventure. Bazaz shares his insight into the filmmaking process, including using some interesting lenses for a nightmare sequence and achieving a fable-like feel in the grade.

In this NFTS short film, a depressed jester sets out across plague-ridden England to rescue the Queen’s nephew and prove he is more than a fool.

British Cinematographer (BC): Why did you decide to study cinematography? Please tell us a little bit about your filmmaking journey so far, as well as your influences and inspirations.

Bart Bazaz (BB): For me, cinematography is a perfect cross-section of technical craft and creative expression. I came from an art and design background specialising in fine art at Chesterfield College, where I discovered a love for illustrations and conceptual art. This led me down a path of 3D animation and character design at Nottingham Trent University with a heavy focus on narrative world-building. Artists like David OReilly were a massive inspiration for breaking convention.

It wasn’t until I graduated that I discovered the immediacy of a camera best suited my creative pace. Five years of camera assisting in short-form commercials and narrative led to me taking up the role of cinematographer myself, shooting dance films and narrative shorts with my partner Margo Roe, who was coming up as a director at the time. Taking on a masters in cinematography opened up a world of opportunity to return to my art school days, experimenting with process, and meeting new collaborators.

BC: What were your initial discussions with the director about the visual approach for your film? What look and mood were you trying to achieve?

BB: Really early on, director Harry Sherriff sent me a 50-page document of images; dramatic misty landscapes, mysterious and intriguing portrait-style closeups, and extreme wides with solitary silhouettes. Variety was something we said time and time again – how do we pull off the feeling of a quest in such a short period of time? We also wanted the film to have a sense of scale, but not overstretch itself and try to do more than it needed; it was a fine balance.

It was always as simple as “a depressed Jester goes on a quest to raise his status”, so how do we portray his state of mind and show his internal shift. We wanted to mirror this somehow with the prosperity of the palace drifting away as he approached the plague village of Stockley.

Jester is inherently a 17th-century period piece, but something fun Harry posed was, “What if we looked at this like it was a Western?” There’s a bold visual clarity that could come from an approach like that, and I think we pulled some of it off in the final film, particularly with the scene of the priest that feels like a cautious stand-off in its staging. The film is also a commentary on modern politics, so we discussed creating something visually fable-like as opposed to grounded in realism.

BC: What were your creative references and inspirations for your film? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

BB: The film was inspired by Jan Matejko’s iconic oil painting Stańczyk, depicting a depressed court Jester slumped in a backroom chair. It’s a perfect piece for the themes of class, power, and status Harry wanted for us to explore visually. It’s also a fascinating psychological character study of the ‘sad clown paradox’. As soon as I saw the image in the pitch, I was sold. It’s rich and dense in colour, and simple, yet theatrically playful with its composition.

With a lot of the script set on the road, we looked at the work of Adriaen van de Velde, a master of 17th-century Dutch landscapes. I fell in love with his colour palettes, layering of elements, the often-included leading lines of the winding road, and the way he framed and gave head room to the trees, to give a sense of scale and adventure. This style is prevalent in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975), an obvious reference as every scene is like a painting. It was something we would fall back to; “If each scene of Jester were a painting, what would it be?” It really helped us solidify the intention of each scene. The Devils (1971) was a fun look at a depiction of plague, and Days of Heaven (1978) for its vast landscape backdrops and biblical ‘end of times’ finale.

I have a love for any contemporary take on period stories. We looked at The Favourite (2018) for its fun visual language, but more so for how its lensing changed the feeling of a character’s status. I also brought forward The Green Knight (2021), as it is very much fantastical in its playful use of colour and large-format work. It was also around the time Dan Atherton’s work on Great Expectations (2023) was on BBC, and I loved the high-contrast, rich look of the show; it got me excited to lean into a version of Jester shot on digital.

BC: What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed?

BB: Everything was shot on location. A big ambition with the project was the number of locations we were trying to cover in our schedule for that visual variety of the Jester’s journey. That said, we did have one constructed set element in an open field at night, where our production designer Margarida Caetano Dias created a royal four-poster bed that we wanted to glow in the dark with candlelight for a nightmare sequence.

Quite early on we were able to secure Waddesdon Manor in Aylesbury for our exterior palace; a French Renaissance-style château that we fell in love with for its storybook and European sensibility. We had long discussions with Margarida on how architecturally accurate we were going to stay to the loose fictitious dates of our plague set in England. Taking license from Kubrick’s amalgamation of locations in Barry Lyndon, we went with what would feel right on screen for its scale and feel of opulence and power.

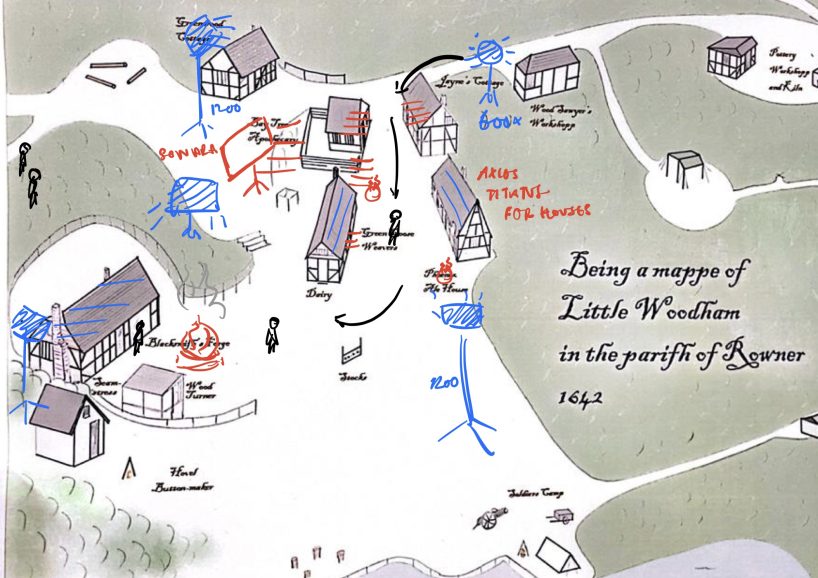

For a matching interior in the opening scenes of the film, we used Claydon House for its large windows and ornate detailing. For the plague village at the end of the film, we shot at Little Woodham, a 17th-century living history village in Gosport. I found this early in prep and suggested it to production for how authentically presented it was. The way the village was set into the trees felt like we could cheat it as small or large as we wanted for our ambitious night scene.

We worked with the Hall Barn Estate in Beaconsfield to place the priest scene beneath a great sprawling tree in a clearing in the woods to make this feel like a set piece. And for the meeting of the boy and some travelling sequences, we spent a day at Blackheath Common. I pushed for a long time for tall Scots pine trees that felt at home in our Dutch painting references.

BC: What camera and lenses did you choose and why? What made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

BB: I pitched the idea of large format to Harry quite early as it felt like the project was very much about faces and spaces. We wanted the film to have that sense of scale, and make the characters feel big and present in their close-ups, or really isolate the Jester from his surroundings in moments of doubt. I did some testing with the Sony Venice and loved the way it rendered a quite high-contrast image.

On a practical note, the internal NDs were a lifesaver shooting so many scenes in open exteriors. We were fighting the sun going in and out throughout our shooting schedule, particularly with the camera quite often being on Steadicam, allowing me to rush in and make last minute exposure changes without affecting the rigs’ balance.

I reached out to ARRI and worked with Simon Surtees to find us a perfect match for lenses; something modern yet characterful. We opted for the DNA LF Primes which always surprised us with their character, particularly the 75mm which we used for a couple POV shots for a more detuned look around the edges.

I made a request to Simon for something even weirder for some highly subjective scenes; one that didn’t make the cut which was a daydream of the Jester romancing the Queen in the Palace gardens; and another favourite of mine in the film, the nightmare sequence of the bed in the field at night. We were very lucky to get to use some prototype T-Type Portrait Lenses, similar to a Petzval, and a Hero Look Lens, where we could manually detune to taste in our closeup of the queen.

BC: What was your general approach to lighting?

BB: The project posed a fair few day exterior scenes, for which we had clear blue skies for all our recces. I was initially wary of the harsh summer sun, but rationalised it for our story. I’d nailed all my timings with the AD team with the suns position in mind, only to get overcast and partially cloudy throughout the week. In the end the real battle was patience, waiting for cloud cover to try and retain some consistency, or shoot for clear sky when it felt right. We used a lot of large frames of neg where we could, and even camo nets for the priest scene to break up sunlight to match our tree cover.

For our interior scenes, I wanted to stage our action against the beautiful large windows of the space and strike a balance of it looking natural, but not letting the shadow side go too dark. We used an 8×8 frame of thick diffusion camera side with an egg crate, and a Panalux Sonara to dial in our contrast ratio as broadly as possible, whilst wrapping the window light around with diffused Gemini panels. For night exterior work, we wanted rich warmth from any fire sources, and worked with SFX to light with gas fire where possible, or custom tungsten wagon lights on dimmer packs for a more organic flicker in closeups. High output LED fixtures were our main approach for large exterior spaces for their quick adjustability, using large 5/10kWh battery power banks to keep us on the move with our tight schedule away from power.

BC: What was the trickiest scene to light?

BB: The plague village was by far the most ambitious day in our schedule and had the most requirements for lighting. We also only had one 13-Amp outlet in the village, and budget didn’t allow for a generator. We worked with Greenkit who generously helped us with enough power bank batteries to power all our LED light sources.

With a two-hour travel time at the start and end of the day and a couple daylight scenes to shoot, we were on a very tight schedule. I spoke a lot with my gaffer, Harrison Newman, in prep about the construction of the night scene with the jester exploring the village leading up to the bonfire reveal. With the camera on Steadicam covering a fair distance, we had to light a really large space so that we could almost set it and go from shot to shot with minimal adjustment.

In the lead up to sunset, Harrison went about setting our large spread moonlight sources at each end of the main way; an Aputure 1200D and 600X. We had a Panalux Sonara up on a mound set to match our firelight with its great CCT range, high output, and spread, and this did a great job to push level between the houses as the jester walked in and out of shadow.

In the houses, we dotted battery-powered Astera AX10s for splashes of light to reveal certain details. We were lucky to have Matt Strange SFX on the team who supplied gas powered fire, essential for the big bonfire shots. He also rigged braziers that were dotted throughout the street on the approach which also helped add more motivation for our lighting.

BC: Who did the grade and what look did you want to achieve?

BB: Coming from my background in 3D animation and compositing, I’ve actually graded nearly all my work over the last two years during my time at the NFTS. I’ve found it massively useful in seeing how the images I capture can be manipulated in post, which in turn has helped me play and experiment with my process on set.

Something I wanted to do on Jester was aim for a colourful and contemporary high contrast look. I had a vis-doc of punchy commercial images that were really dense and rich in colour, even though this got tamed back through the process. Whilst shooting relatively soft/lower contrast on set, I worked with a contrasty base grade to bring out a lot of micro contrast, particularly in the jester’s skin to give a feel of texture and dirt. I supplemented this with some subtractive colour work to bring density to the red of the jester’s outfit and make that a hero colour in connection to our film’s original reference. Something I always hoped to achieve was that slightly fable feel to the film through colour, and avoid anything predictably period looking, be it too desaturated or low contrast.

On a side note, I had a lot of fun with a specific day-for-night establishing shot before the nightmare scene. For this I scouted a location and scheduled for a specific time of day for the sun, and was lucky with soft cloud cover that eliminated any hard shadows. I did a lot of shaping in the grade to recreate the feeling of our painting references to lead the eye to the woods in the deep background.

BC: What is your proudest moment from the production process?

BB: Achieving what we set out to get from the plague village day with all its time constraints was a proud moment; coordinating my camera and lighting team, and working with a great plan and seeing it come together. I think night exterior wides are notoriously difficult in any cinematographer’s opinion, so pulling off something that fits with the look we set out to get feels like a great achievement.

BC: What lessons did you learn from this production that you’ll take with you onto future productions?

BB: Getting through shooting Jester gave me a massive confidence boost that I can handle more ambitious projects of this scale. With ambition, you ride the line of what’s possible under a lot of pressure, and not having enough time to craft. Despite it being the nature of modern cinematography, I think really interrogating a schedule in prep so you have enough time to craft is very important.

BC: What would be your dream project as a cinematographer?

BB: For me, I love anything that plays with genre and is witty, stylised, or off-kilter; something like the true crime dark comedy Landscapers that’s playful and subverts expectations. I’d also love to work on a really high-end, gritty fantasy or grounded sci-fi; an adaptation of some of Simon Stålenhag’s darker work like Labyrinth would be really cool.

BC: Is there anyone not yet mentioned that you’d like to highlight?

BB: My Steadicam operator Lee Brown dedicated so much time and effort to the project, I’d be doing him a disservice if I didn’t give him a shout out. I felt so grateful to have the chance to collaborate with him, and wouldn’t have been able to create a lot of what I hoped for without his support every day of the shoot. Our instincts felt so aligned and it was a pleasure to explore our approach with each scene.

There’s one little scene of the jester walking by two coughing girls on the road, and I always envisioned this very subjective walk-by POV. It’s such a simple sequence, but for some reason to me it felt like a real moment from the movies and of world building. I remember Lee turning to me after a take and, unprompted, he said he felt the same thing. It was a little reminder of how collaborative the work we do really is, and why I love the job.

Read the rest of our series spotlighting the NFTS’ 2024 cinematography cohort.