FUTURISTIC VISION

Remaining as nimble as possible during shooting saw the filmmakers behind The Creator change the methodology of making a blockbuster and work with multiple camera configurations including easy-to-assemble prosumer equipment.

More often than not, two cinematographers credited on a major Hollywood movie spells trouble, but then Gareth Edwards’ The Creator is not your typical blockbuster. Before the pandemic, British filmmaker Edwards began planning this AI-themed sci-fi with Greig Fraser ASC ACS, his Australian-born cinematographer on 2017 Star Wars spin-off Rogue One. Yet as the world went into lockdown, so The Creator – then called ‘True Love’ – went into limbo. With Edwards planning to shoot across Southeast Asia, he was forced to wait until countries began opening their doors again.

Finally, in the autumn of 2021, pre-production got underway in Thailand, with shooting due to commence in January 2022. Fraser, though, was committed to Dune: Part II, which meant another cinematographer was required. He found the perfect choice in Oren Soffer, a rising star in the industry who studied at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, where he was nominated for the ASC Gordon Willis Student Heritage Award. Since then, Soffer has shot commercials, music videos, shorts and features including the 2022 thriller Fixation.

When Fraser suggested Soffer, a Zoom meeting was set up between the three of them. “Gareth is kind of a rebel,” says Soffer, speaking over video from his home. “And his whole concept with this film stems from his nature of questioning how things are done in the industry…like the normal way of doing a big blockbuster film. And this is something that he and Greig explored on Rogue One quite a bit. How to change the methodology for a big film like this, in a way that doesn’t keep you confined in a box but opens up the opportunity for spontaneity.”

It’s a daring notion, especially when you consider the huge footprint a blockbuster leaves. But Edwards, who likes to operate the camera himself, wanted to shoot nimbly, in the way he did for his debut feature Monsters (2010), made with a skeletal crew. As Fraser explains, this was becoming increasingly possible thanks to the evolution of lightweight camera rigs and lighting equipment available on the prosumer market: “Even though it still says ‘prosumer’ we’re like, ‘We could make a movie with these cameras and these gimbals.’”

In the run up to production, Edwards and Fraser chose the Sony FX3, a new-to-the-market lightweight camera capable of operating well in low light. Fraser shot some tests with it on a commercial in Spain. “I showed Gareth the results, and they were great,” says Fraser. “So, we kind of made that the centre point of the system, so that Gareth could have a camera, he could keep it on him the whole time. He could travel to set with it, he could keep it under his bed at night!” Fraser also sent footage to the Burbank-based post-production facility FotoKem, where colourist David Cole would be working on the grade.

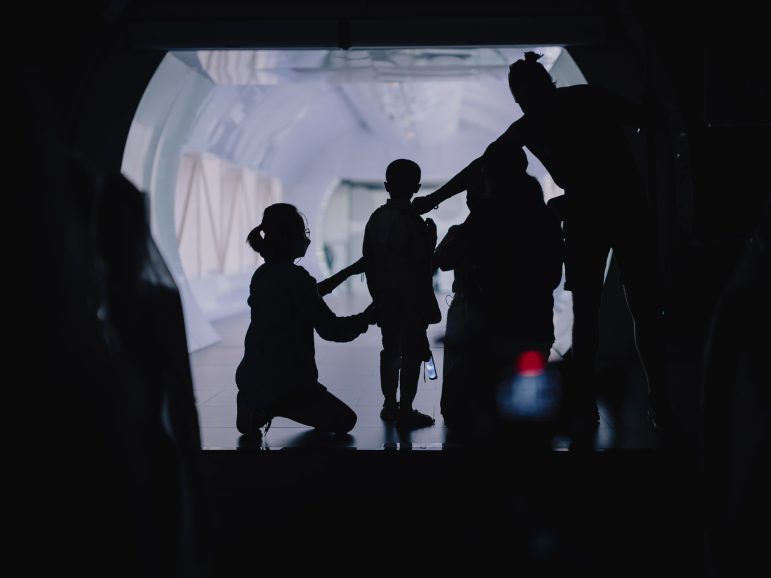

Largely set in 2070, fifteen years after AI caused a nuclear explosion to detonate in Los Angeles, The Creator is set at a time when the US has built an orbital weapons system, NOMAD, to hunt down the remaining AI in the Republic of New Asia. The story follows the unlikely partnership between a former soldier named Joshua (John David Washington) and Alphie (Madeleine Yuna Voyles), an advanced AI (or ‘Simulant’) child. Although the end result would require thousands of visual effects led by esteemed VFX house Industrial Light & Magic, early meetings between Fraser, Soffer and Edwards helped set the tone.

“To me, that was one of the most beautiful things that came out of the project…that relationship that formed between the three of us,” says Soffer. “In pre-production, Gareth, Greig and I spent quite a bit of time on a Zoom call looking at reference images.” After scrutinising this wealth of material to develop the look for each scene, they were then able to take the Sony cameras onto the location scouts, filming test shots with Edwards’ lens of choice: the 75mm Kowa Anamorphic.

“It’s a vintage Japanese anamorphic lens,” explains Soffer. “I think especially Gareth was very inspired by wanting this movie to feel like the sci-fi films from the ’70s that we all grew up with and loved, like Blade Runner and Alien and Close Encounters. They tested a bunch of lenses and landed on the Kowa 75 as the perfect nexus of the look and feel that they were after. But also, something lightweight and small, that would have the least impact on affecting Gareth’s ability to handhold the camera for thirty minutes at a time for a 90-day shoot.” For tight interiors, inside vehicles, the team also used a prototype Atlas Mercury 42mm.

Agile shooting

When the shoot began, Edwards was forced to scale back on his desire to shoot in other Southeast Asian countries, due to COVID-19, and remain in Thailand, although after principal photography was complete, a small unit would visit Nepal, Japan, and Cambodia, with second unit director of photography Andrew Michael Ellis filming background plates. Echoing this, the idea was to remain as nimble as possible during the main shoot, aided by easy-to-assemble prosumer equipment.

Multiple cameras were built in different configurations. One was held on a handheld gimbal, another on a dolly that could be transferred to a scissor crane, while another was dedicated for drone footage. “It was maybe challenging a little bit for the grips, and the lighting department to get used to these tools, because they’re not the typical professional tools that are used on set, but they very quickly got it,” says Soffer. With the production also able to buy the equipment rather than rent it, it gave the crew time to practice.

By this point, Fraser was back in London, but remained on call. “Once we started filming, Greig would watch dailies, and I would send him stills from every day’s filming,” says Soffer. The first couple of days, in Bangkok, which doubles for the futuristic Lilat City, allowed Soffer to truly nail the film’s look. “We were shooting on the streets of Bangkok and shooting in these available light scenarios. And I think that’s what Greig was particularly excited about, leaning into the flaws and leaning into the available light.”

When required, Soffer deployed Aputure LS 1200d Pro LEDS. “It’s a 1200-watt light, which is very low output for lighting a huge area. Because of the high sensitivity of the camera, we were able to place those lights in a lift, quarter mile away from the set, and just have them blast this hard moonlight wash, an artificially created moonlight feel. And those lights can run off a small handheld generator.” Interiors were lit with Aputure MC lights, small battery-powered units, and also the Rosco DMG DASH, which offered “a different quality of light…in terms of softness”.

With Edwards operating the camera, Soffer and his gaffer Pithai Smithsuth sat by the monitor. “We had a very lightweight mobile monitor that we would place as close to Gareth as possible without being in the shot. So sometimes we were just around a wall or hidden behind some obstruction. So, it was as close to set as possible without potentially being seen by Gareth’s 360 degree shooting style. And then Pithai and I were orchestrating the lighting from there. So, we were both on headsets [as were] the entire electric team. We had a dimmer board operator who would control any ground units that we had.”

The team also developed an unusual method of mobile lighting to complement Edwards’ liking for long takes. Best boy lighting technician Nancy Kang carried a Helios Tube, a two-foot LED battery-powered tube manufactured by Astera. Placed inside a softbox, it was attached to a boom pole held by Kang. “Nancy would react to where Gareth was going,” says Soffer. “[So] maybe he tilts the camera down for 30 seconds to talk to the actor, and the camera’s still rolling. But we would take advantage of that little window to readjust the lighting really quickly. So it was like live stage lighting, where you’re reacting to things in real time.”

While The Creator was a one-camera operation for the most part, some of the more complex sequences saw the team divide and conquer. As Joshua and Alphie venture through New Asia, encountering pockets of AI insurgents, the US military send in the big guns for The Creator’s showstopping centrepiece, as tanks roll in and start blasting a village and nearby wooden bridge. “For some of those sequences, we had a second camera, just to get some additional action angles. So, I would hop on the second camera every once in a while,” says Soffer, who also helped shoot drone footage where needed.

The divide and conquer method also proved vital for the shoot’s final ten days at London’s Pinewood Studios. Capturing sequences from the final act, as Joshua and Alphie jet into space to destroy NOMAD, some of this would be shot on the volume. Fraser had already pioneered StageCraft technology during his time on Star Wars TV show The Mandalorian, shooting with virtual environments as if they were real locations. Here, he was able to work with the team from ILM while the main crew finished up in Thailand.

Environments created for the volume included NOMAD’s Biosphere, with hundreds of real plants also added onto the stage in front of the LED screens. “The thing with volume photography is that it requires a huge amount of prep and understanding of what you’re doing in advance, which was kind of against the methodology that we had for the shoot,” notes Fraser. “It wasn’t that we didn’t go and prepare. We gave Gareth the proscenium of the world to shoot in as much as possible. Whereas when you volume shoot, it’s really important that the design is locked in, because it’s in camera. So, it was kind of a very much a 180 from where we were.”

Switching cameras to the Sony FX9 (the FX3 “doesn’t sync with the LED walls on the volume” notes Soffer), it was Soffer’s first experience on the volume. “I think it’s very much an emerging technology. And there’s still a lot of technical limitations and difficulties that are being worked out to streamline the process and make it an even more powerful tool. But the principle, the concept of it, and the feeling of standing on a set with it and feeling like you’re immersed in a space – and getting the interactive lighting from that space, and how it affects the practical portions of the set that you built – was really, really powerful.”

Shot on a reported budget of $80 million – far lower than most VFX-driven movies of this scale – the question still stands: will The Creator revolutionise Hollywood? And did it accomplish a scaled-back production without compromising on quality? “I think it does,” says Soffer. “[It was] very different and unorthodox from any other project that I had filmed. In terms of that approach – the lighting approach, Gareth operating the camera – it all contributed to something very unique. And I do think that we pulled it off. I hope we pulled it off! But it’ll be up to the audience to decide whether the film does feel immersive and authentic. That was certainly the goal.”

–

The Creator is on general release.