Talking Cinematography is Zeiss’ new format to talk about cinematography, technology, development and much more.

Their first topic: The award-winning thriller Titane left the viewers breathless. Zeiss talked to cinematographer Ruben Impens SBC and his ACs Charlotte Vitroly and Baptiste Nicolaï about the production, challenges and the team’s collaboration on set.

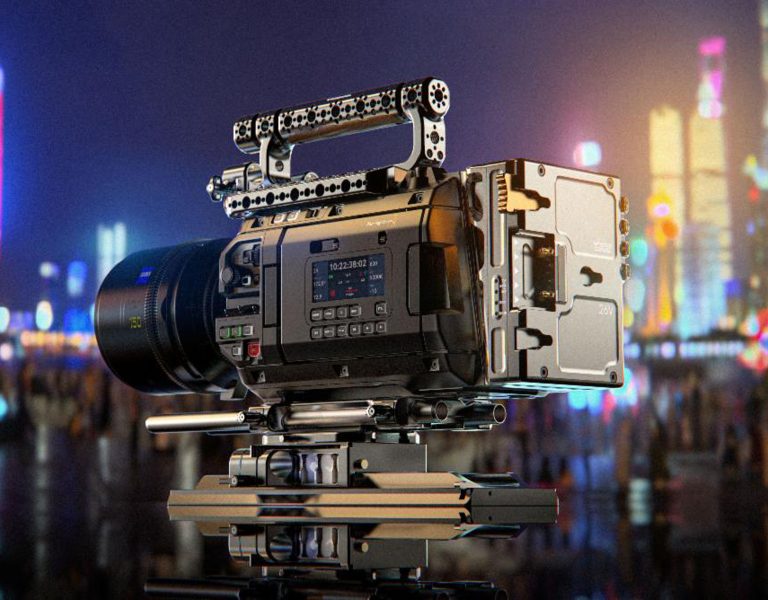

Ruben Impens SBC: I was really happy with it. The look we were aiming for was quite modern, saturated and contrasty with a lot of details, that’s why we used the combination of the Alexa LF and Zeiss Supremes. We didn’t do that much testing for it: I had used the lenses before on a commercial, I just showed it to Julia and she was pretty happy with the result, so we went for it.

Julia Ducournau said that she began writing Titane during the postproduction of Raw. How did she disclose the project to you?

She sent me a draft of the script, which was still in three chapters by that time, not like one complete story. The elements were there but she was still working on it.

What was there at the beginning that is still here in the end, in the finished film?

Even in the three-chapter version, the soul and the core of the movie were already there. What changed is just the way it was told. It took too long before the two main characters reunite. Let’s say it became more human during the production process. It may seem strange for this movie; however, it did! To me it became more emotional, and I’m always more interested in the emotional part than in the shocking part, the visual affects; of course, it’s important, but in the end, I think it isn’t what makes it a good movie. It’s a very strange emotional trip.

Maybe it became more human once you had actors in front of the camera.

Obviously. It’s the most interesting subject. It’s also what’s interesting in Vincent Lindon’s character: there is so much history and soul in the body of his character, and you see it right away. I was really surprised by the way he turned out in the end.

Did you share any visual references with Julia Ducournau? Did she mention other movies, or directors?

Not so many movies, it’s more photographs, sometimes pictures; we can talk about painters like Francis Bacon, or Caravaggio’s kind of lighting, but it’s just a language for us to quickly understand. We looked at Gregory Crewdson’s photographs, which present very lit and artificially composed installations. But we didn’t say “let’s try to do that”, Julia doesn’t work like that. Very little references to other movies and choreographies.

Maybe music?

Yes, she knows what she wants and it’s cool. For the opening sequence, we knew what it would be. She is pretty visionary and accurate. During the four-week preparation we shot listed, looked at the locations. She is very aware of timing as well: special effects and makeup are hard for the actors, you just must not work overtime, and many times she is the one who says: “we have to kill the shot here, it’s too much!”.

If in the first meetings she has an idea of the general mood, I start looking around. I knew it had to be spherical and not anamorphic, it was quite obvious, for esthetical reasons and for the feeling that comes with it. We wanted fast lenses and at the same time minimal close focus, so that when one ran away, we could follow the actors with the focus. It was a quick decision.

Did you go directly to large format?

I had used the Alexa Mini for three or four years, and for Raw we had a vintage Zeiss High Speed mk III set of lenses, of which we used the wider lenses. But it was frustrating, because we were going for these wide shots in scope where you see figures walking, and when we saw them in a big theatre, we had this lack of definition. The Alexa LF in combo with the Supremes were all we were looking for, it was great.

You went to large format for the wider angle of view and the greater definition: it was just waiting for you to pick it!

Absolutely. It was perfect for the movie, with what you can do in post. I’m a big fan of this small camera.

I thought a lot of your assistants camera watching the film, because the depth of field is ridiculously shallow…

I know, Charlotte did an amazing job, it’s true. She had a great team as well. We had some difficult sequences and I know how critical it is. However, I don’t shoot wide open, I’m not such a big fan of “blur”. I like to be able to see the set if it’s good, I aim for a T2, 2.8 +… Right now, I’m shooting in the mountain and it’s the assistant camera who tells me “I can do that, you don’t have to shoot at 5.6…” but I want to see what’s there! Many times, now, with large format, I see stuff and I think “why so little depth of field”. Of course, in some situations it’s interesting, it’s a tool to play with. The cool thing, for instance on Titane, is that you can shoot with a 29 or a 25 mm, at T2, 2.8, and you will have a nice fall-off, although it’s a very wide lens. For Titane it was perfect.

In an interview Julia gave during the Cannes festival, she described how she chooses the focal length for the shot with you. It’s a tool she knows, doesn’t she?

Absolutely. She is a very quick learner. Compared to Raw, her first feature, there was a big difference. We know each other better of course, after having made a feature together it’s a different collaboration. I think it was more defined during Titane, I could feel that she was more into it and that she wanted to take another step, be more aware.

Did you have any storyboard?

We did some storyboarding, but only for the sequences with a lot of SFX and VFX, to make the conversation with the crew fluid during the prep meetings. We storyboarded three or four scenes, especially the fire sequence in the woods.

For the “regular” sequences the shot list is made of descriptions. And when we read it again six weeks later, we sometimes went “what?!” [laughs!] I’m a big fan of trying out things. We try lower or higher… The shot is getting more and more precise, towards the moment of the shoot. Some scenes are very simple as well, to leave room for acting or dialogue.

I imagine that the big oner at the beginning, when Alexia enters the car show, was there from the start. Maybe it was already written in the script.

It wasn’t written but her journey was described. The intention to do it in one shot came out very early in the prep. It was the first shooting day, and that was great! Of course, there was a lot of prep involved, we had a full day rehearsing. It was shot in a big hangar in Antibes, in the South of France. It is not a sound stage, and as you could see we used the structure of the building. We designed it step by step, we made a sketch… How can we start, how can we break up the big room? Then we came with the containers… It’s weeks and weeks of refining. Then we taped it on the floor and started rehearsing with a stand-in. This, for me, is hard working, but Julia really has the skills of putting that together, a great feeling for timing.

The lighting often is sophisticated, with many sources in the frame, such as the headlights of the Cadillac…

From the start we wanted a big contrast, and a backlight hitting the lens gives you this. I think it completely matches this whole idea of glimmer, shininess, brightness of the reflecting metal. This was something that we enhanced every time we could, throughout the whole movie. All the lighting was on a dimmer board, to avoid camera shadows when she moves at 180°: the gaffer needed to be able to fade out when the camera turned. It was a lighting choreography. Nicolas Lagae, the gaffer, did an amazing job: it’s complex, not so many can manage it. On small sets we had a Gaffer’s Control, and for a big scene like the oner, I think he had even two consoles! We had like eighty sources.

But it’s worth it! You can see it on the screen.

It’s very lit. Sometimes I was wondering if it wasn’t too much. We used the light to tell the story, to push it further and from the start, it was Julia’s idea. Sometimes it’s bold, for instance, when Alexia comes to the house where the parents live, it’s only one source, the practical light of the motion detector. For interiors we used colours: the light has an emotional function, it’s not realistic.

The first part looks cold, almost blue, then you discover Vincent’s pink bathroom, and you have a pink wash all over the place; the firefighters’ party is purple, isn’t it?

Hard to say… It’s one of the colours that people see differently, some call it fuchsia! For us it’s pinky, but the colour grader never called it pink [laughs] We tweaked it, but it was done on set, because I mixed it with a colder green light from outside.

I think I recognised a split diopter here and there…

Yes, we used one in the bedroom, where Vincent turns his back towards Alexia when she is in her bed, to have them both in focus. It’s not so common with spherical lenses, but it kind of works. Well, it’s an effect…

It is, but it’s what I like about Julia’s films: the effects are visible, because it’s cinema! In cinema there are effects!

Exactly, to me as well! This is why it’s nice to work with somebody like her, for a DoP: she isn’t afraid of using the camera, the lenses and the image to tell her story. She is not interested in reality! For Raw we used a boroscope for three or four shots, when the camera travels from very close to far away at the last moment, and after the car crash, the camera approaches so that we discover the body and then goes through the window… I bring it on, and although she doesn’t have a technical background, Julia knows: “that would be great if we could do this! It’s amazing!” That’s what I mean with quickly learning. She has the images in her mind, for me to translate. “Be careful” is not in her dictionary. In her vocabulary, it’s more “let’s take the risk, let’s try, and if we fail, we fail.”

What about camera moves? Did you intend to stick to the moves of the actress?

This was never one of our axioms or intentions, it wasn’t in our language. It’s more subjective… Many times, the camera is moving by itself, the movement isn’t motivated by the character. If they do a pogo, or if we show the liquid of the car, it’s a lot about describing, narratively disconnected from the character. I did movies where it was much more the case, it was one of the rules of the movie, for 85% of the movements. In this one, it’s more like a classical way of cutting. If you see her walk into the car, we just observe, we are not going with her into the car, and the shot stays long before cutting to the car. Except for the opening oner sequence, of course.

Was it more about rhythm? The camera often is very sensual.

Yes, but at the same time it’s very static. I think you’d be very surprised to know how many shots are fixed. A lot. I’d say more than half of the shots. Sometimes we had a shoulder camera, because narratively we want to give like a normal everyday life scene feel, and stay with the characters, not have an image disconnected from them. For me, something like a gentle shoulder camera always gives that feeling, with a normal lens like a 32 or 40 for a medium shot, I have the feeling I am with that person.

What about your workflow? Did you have LUTs on set? Did you see dailies during the shoot?

Not really. Julia doesn’t watch dailies, she doesn’t want to spend time on it, she has them in her mind. I worked with one in-camera LUT. It’s a very contrasty LUT. I got rid of it for the movie I’m shooting right now, it’s too dark, but it was great for Titane. It’s a very steep curve. At the beginning, my gaffer was like: “we have to put so much light!” It’s based on film emulsion, it’s nice, but dark and contrasty, and you must light it otherwise it won’t work, you just don’t see the faces, it’s crazy. It was our basis for the grade. Sometimes it went too far, there was a lot of blue in the highlights, sometimes it’s too “Instagramy”, as Julia called it, and I totally agreed, so we took it back and balanced it.

How did you work on the texture of the image?

We tried to add grain in post a little bit, but we didn’t apply any. We only had the onset filtering of the Radiant Soft filters. Moreover, we didn’t shoot in ArriRaw, but in ProRes: strangely enough, I like it… It’s slightly different. The image is already so sharp!

We could say that shooting in ProRes with such bold choices could be a way to make a strong artistic statement: there is no going back, the look is baked in.

That’s true, it’s also what I like about it. As the sensor is just double the size we needed, we didn’t shoot full frame, we cropped the picture for the 2.39 aspect ratio. But Julia didn’t mind, a frame is a frame! Of course, for the big oner in the beginning we kept the whole sensor to be able to stabilize a little bit afterwards, and for a few other shots in the movie, but on the rest, we cropped the ProRes in 2.39. The full sensor doubles the data, and we don’t need it.

Were you involved in the research for the prosthetics, such as Agathe’s scar, her pregnant belly, the black oil-blood…?

Julia is very into it you know. It’s really hers. Elements like viscosity… it’s something she’s very precise on. I’m there and aware of it, but it’s her part. Because I know it’s going to be good!

Charlotte Vitroly, 1st AC

ZEISS: It was the first time you worked with Ruben Impens – how did you meet?

Charlotte Vitroly: It’s Baptiste Nicolaï, the B camera and fire scenes operator who gave my name to Ruben. I didn’t have many arthouse movies on my resume, but I had worked both on shoots with significant means, and tv movies where you need to work fast, so I could be versatile enough. After 10 minutes over the phone, Ruben said “ok, I’m sending you the list”. He is confident! I had really loved Raw and I’m a fan of Julia’s references, such as Bong Joon-ho’s and Na Hong Jin’s films, so I was eager to work on this project. What’s more, Baptiste had insisted: “it’s the film of your life, you must say yes!” [laughs!]

You were at Lites, a Belgian rental: does choosing and testing the equipment happen like it does in France?

It does, more or less; some tests may not be as extensive. We asked to calibrate the monitors, and to compare the colorimetry of the cameras, which surprised them. I think it’s because they work a lot in postproduction and know the performances of the Mini LF: they are not worried. Working with them was quite pleasant, as they were very attentive, available, and accommodating. We had to fit the list to the budget as closely as possible, so we didn’t take the extra equipment we usually have to meet requests we didn’t anticipate. Let’s to put this in context: we knew neither Ruben’s nor Julia’s way of working.

What items did you insist on keeping?

It was down to the spare wire, the batteries… We prioritized the tools that facilitate our work. In particular, the HF monitors, not only because we pull focus on them, but also because it’s more comfortable for the director and the crew. I had suggested to Ruben we take the Arri WVT-1 HF monitoring system: considering the script and the planned shots, such as this oner mixing the Ronin and a crane and the many handheld shots, keeping it was important, even if it is what costs the most. We also worked with a QTake for playbacks and some VFX previsualisation. It was quite expensive, but it allowed us fluidity and versatility, which matter to Ruben. We crossed all the usual spare items off the list.

Batteries, cards…

Yes, also.

Ruben shot in ProRes! Hence, less cards.

Yes indeed, he knows the Mini LF and what he is doing!

You recruited the other ACs?

I did, Ruben trusted me and let me choose. I didn’t know Antoinette Goutin, but I had worked separately with Lucien Jacquelin and Thomas Hauser. The mix was new and worked pretty well!

You had two cameras.

Yes, for about fifteen days.

How did they work for the setup? Was there a main camera for the shot, and the B camera trying to find its place where it could?

Not really. Julia knows exactly what she wants, she has a specific idea of the shot. The film is deeply structured, in terms of framing and even of lighting. There was no such thing as chance. The scenes with two cameras generally were very thoroughly planned, and we sometimes had to let go of the B camera, because it required too much compromise on the main camera.

B Camera Operator Baptiste Nicolaï

When I met Ruben, he was looking for a camera operator to help him shoot this complicated oner, where Agathe enters the car show. I operated the first part of the shot with a Ronin, until I hooked it on the Technocrane and Ruben took over with the handwheels. The shoot started with this shot. We had a day for the rehearsal, beginning with my part on the Ronin, the dancers and Agathe’s double. I had operated shots with partly a handheld camera and a crane before, but this time we used a new technique, working with a powerful electronic magnet, which we would activate when I arrived underneath the head. The crane sometimes wasn’t exactly where we were supposed to meet and I had to adapt: it was a meeting not to be missed between me, the Technocrane operator and the grip. It took a subtle coordination, like refuelling an aircraft in flight.

The next day three hundred extras came for the shoot, and what we had achieved in rehearsal didn’t work anymore! The camera operator sometimes is better able to block the extras than an assistant director, so Julia allowed me to make my way through them, as the Ronin is larger than a Steadicam. The story we wanted to tell had to work, without anyone in front or in the way of the camera. We made good takes very early on. On the day before, Julia had motivated us like Napoleon galvanizing his troops before the pyramids! She is demanding, but I saw her jumping for joy when we achieved the shot. Seeing a happy director is great.

I was supposed to shoot as a second camera operator during six days, but I ended working more than twenty-two days. I operated the other oners, and the main camera on the fire scenes. Ruben is generous enough to leave the main camera, and I know how difficult it can be! I enjoyed shooting the fire scenes like a child! They were entirely handheld, because it would be impossible to protect any other equipment from the heat, and you need to be one with the camera, in case you must run away quickly. One time, as I was walking backwards to a room where Lindon entered, they lit up a flame bar close to me: I felt the intense heat on all my leg and flame brushed the camera. Obviously, Julia was thrilled to have the flames on screen! The one time I didn’t put the “pirate protection” for the eye that wasn’t in the viewfinder, I soon felt my eyebrow burning and ran away. But we always had firemen and grips with us, and I never felt in danger. Everything was cautiously planned, even if Julia leaves room for the intuition of the operators.

It wasn’t the first time I shot in large format, but I was the first time with the Supreme Primes on a feature. They are superb on all levels, not only for their sharpness, but also for their ease of use for a Steadicamer or a Ronin operator, and the for the camera assistants, thanks to the large rotation angle of the focus ring.

What did I learn on this shoot? I learnt how pleasant it is, to work with a director who knows what they want, and not only what they don’t want. Julia is so far away from relying on the image crew!

–

Shared with permission from Zeiss.