White Guilt’s indie journey from script to screen

Jul 14, 2025

Marcus Flemmings personifies the definition of an indie filmmaker.

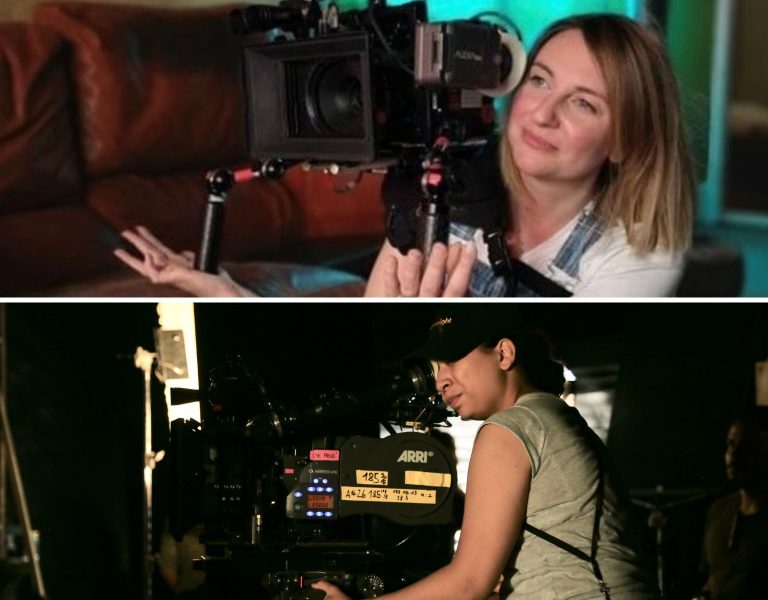

His feature-length drama White Guilt was shot with a tiny crew over just five days, showcasing the benefits and advantages of a long-standing creative partnership with director of photography Haider Zafar and a stripped-back approach to production and story.

Written and directed by Flemmings, the satirical film follows eleven wealthy white millennials who sign up to ‘experience’ slavery as guilt therapy. The unsettling tone is heightened by sparse sets, harsh lighting, and a look reminiscent of the American South, despite being filmed entirely in southern England.

Flemmings and Zafar have collaborated extensively for 15 years on multiple films; White Guilt was their eighth feature. “We always come back to themes of race, religion, segregation and perception,” said Flemmings. “White Guilt is about human connection and the systems that shape it. With this film, we wanted to tell that story more cohesively and maturely than we had in the past.”

The film’s story, performances, and visual style have resonated, earning acclaim on the UK festival circuit, including Best Feature at the British Urban Film Festival 2024 and a slot at this year’s Raindance.

Stripped down on set

Shot on the URSA Broadcast G2, White Guilt blends natural lighting with an intentionally rough aesthetic. “We initially started with a handheld approach, and then we moved on to an Easyrig on day two,” says Flemmings. “But it was always going to be documentary-style, 4:3 aspect ratio, with that gritty, dirty kind of feel.”

“We were chasing God’s light wherever we could; we only brought in an Aputure 600D for a few setups,” said Zafar. “Both cameras perform well in low light. I used Samyang XEEN lenses and tried to stay at around T2.8.”

No makeup artist was used for many scenes, fitting the exposed nature of the storyline as well as complementing the aesthetic. “You can see some people’s imperfect skin on screen,” said Flemmings. “And it was exaggerated once we’d done the colour grade. But we wanted it to be as gritty and as raw as possible.”

The raw approach extended to performance, framing and structure. “Up until White Guilt, I had storyboarded every film,” Flemmings revealed. “This time, I wanted to completely let go of those boundaries, so I decided to just point and shoot.”

“We let the story and the locations guide us. We’d see something on the day, maybe the sun was in a certain place, and we’d capture that. It sounds chaotic, but it was very deliberate. We’d choose the lens and the angle in the moment, guided by instinct and the energy of the scene.”

One of the standout examples of that approach is a sunset scene, where a group of characters stand in a wide field in front of a house. “It was magical,” recalled Flemmings. “The sun was setting just right, Haider was roaming with the camera, and it all came together on instinct.”

“I wanted a tracking shot through the actors, but Marcus said to hold back,” added Zafar. “There was something imperfect in frame that annoyed me at the time, but watching it back, it just worked. That’s the beauty of letting go.”

“Watching that scene in the cinema, the room just went quiet,” said Flemmings.

Shooting in Blackmagic RAW (BRAW) gave the filmmakers future flexibility in post while keeping data management on set straightforward. “You’re always trying to find that sweet spot between how much data you’re capturing and how much you can realistically store and work with,” said Zafar. “We used 256GB cards and a high compression ratio. It still looked great, and we could keep moving.”

Crafting the tone

Editing the film in DaVinci Resolve Studio, Flemmings treated post as an extension of the shoot.

“I don’t shoot loads of coverage; I’m already shaping it in my head as we go, I know what the rhythm’s going to be,” he added. “You can get into the edit and shape it; just removing a reaction shot changes the whole tone of a scene.”

“The first day is spent generating proxies, which takes times. But I use that window to organise everything into bins, grouped by scene. That way, with all the prep work done, I am in a good place to jump straight into the edit.”

He cuts in chronological order to stay focused on the story’s arc. “You do your first assembly, and then you watch it again. You take things out, you put things in, and you just keep going. Draft five was pretty much the final film. When I passed it on to the actual editor, Mike Pike, all he had to do was go in and massage it afterwards.”

Building emotional arcs

“In terms of the look, I always knew that I wanted it as gritty as possible in the colour grade, taking films like Seven and Schindler’s List as references,” he adds.

The final grade was handled by Maggie Maciejczek-Potter at The Finish Line, who started balancing scenes, and then adjusting contrast and tones to build emotional arcs. “We did a session with Maggie to go through the film, and then she did the finessing. We told her to just go crazy with her grade. And she definitely went crazy with it,” said Flemmings. “It’s raw, it’s full of shadows and texture.”

As well as bringing up the definition in the actors’ bare skin, by pushing the grade, Maciejczek-Potter was able to turn Kent and Hertfordshire in November into the uncomfortable heat of the Deep South.

For Flemmings, the creative payoff has come not just in the final cut, but in seeing the cast and crew recognised in the recent run of awards. “It shows that the effort and energy spent is ultimately worth something,” agreed Zafar, who also produced White Guilt along with Flemmings and Katya Chattwell.