Back in Time

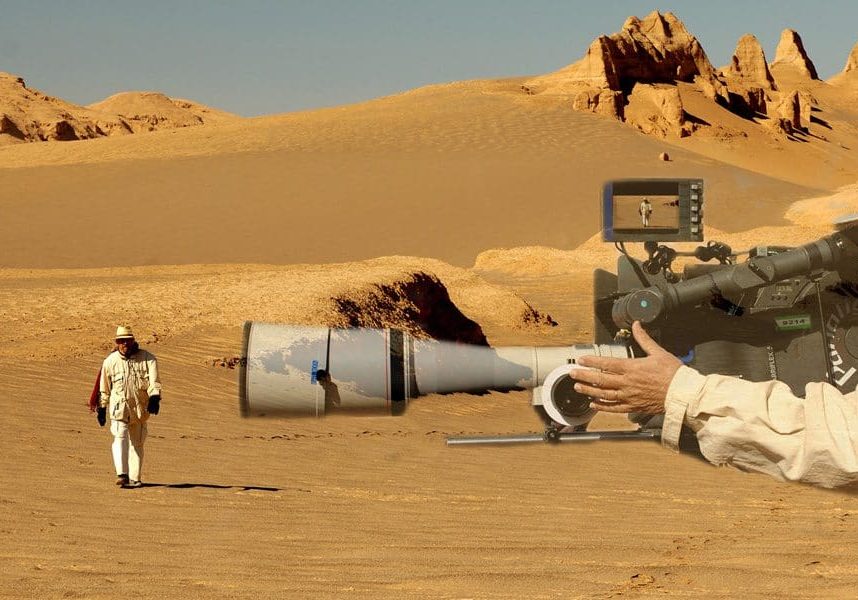

Vittorio Storaro AIC, ASC / The Early Life of Mohammed

Back in Time

Vittorio Storaro AIC, ASC / The Early Life of Mohammed

BY: Bob Fisher

Vittorio Storaro AIC ASC has earned almost 60 cinematography credits for narrative films and occasional documentaries. His diverse body of work is tangible evidence that artful cinematography is a universal language that speaks to people around the world, writes Bob Fisher.

Storaro was born in Rome, Italy in 1940. His father was a projectionist at Lux Film Studio. When Storaro was ten years old, he regularly sat in the projection booth watching films that his father was screening for directors and producers.

“I learned to read images, because I couldn’t hear sound in the booth,” Storaro remembered. “My father dreamed what it would be like to be a cinematographer. He put that dream in my heart.”

When a new projector was installed at the studio, Storaro’s father brought the old one home. The family watched silent movies featuring Charlie Chaplin that were projected on a wall that was painted white by Storaro and his brother.

Storaro was enrolled in a photography school when he was 11 years old. He spent five years at that school before moving on to a cinematographic training centre. Storaro spent his mornings at the training centre and worked in a photography store processing film and making prints during the afternoons. He subsequently enrolled at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia (Italian Film Institute).

Storaro spent his free time studying literature, music and paintings created by Mozart, Rembrandt, Faulkner, Vermeer, Caravaggio and other artists.

He began his career as an assistant cameraman during the early 1960s. Storaro was on the crew when Bernardo Bertolucci directed Before The Revolution in 1963. He earned his first cinematography credit in 1968 with Giovinezza Giovinezza, directed by Franco Rossi. Storaro collaborated with Bertulocci on the production of The Conformist in 1970, which earned accolades from critics and fans.

He collaborated with Francis Ford Coppola on the production of Apocalypse Now in 1978. The film earned two 1979 Academy Awards, including one for cinematography, and eight other nominations. Apocalypse Now also received two BAFTA awards and eight other nominations, including best cinematography.

Storaro earned subsequent Oscars for Reds in 1981 and The Last Emperor in 1987 and another nomination for Dick Tracy in 1990. He is one of only a handful of cinematographers with three Academy Awards. His artful cinematography has also been recognised by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts and his peers in the British Society of Cinematographers and the American Society of Cinematographers.

The ASC presented Storaro with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2001. If you are thinking that he had done it all at that point in his career, think again. Storaro earned another dozen credits during the first decade of the 21st century. He collaborated with director Rachid Benhadj on the production of Parfum d’Alger in Algeria in 2010. That project inspired him to read a book about the life of Mohammad in order to better understand the Islam religion. Maybe it was destiny calling.

“As soon as I finished reading the book, like a magic dream, I received an e-mail from Iran asking if I was interested in filming the first part of a trilogy about the life of Mohammad,” Storaro said.

Director Majid Majidi and producer Mehdi Heidarian subsequently visited Storaro in Rome to discuss Mohammad. Films that Majidi has directed in Iran have earned recognition on the global scene. Children Of Heaven was nominated for a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar in 1999. Heidarian is a veteran film producer in Iran.

“They explained their goal was to produce the first of a series of three films that will help people around the world understand the story of the prophet Mohammad and the meaning of the Koran,” Storaro said. “I asked if the movie will divide or unite people of different religions. They said that their goal is to unite people with different religions. It’s a story about the dignity of human beings.”

The first film in the trilogy focuses on the early life of Mohammad from his birth to the age of 12. Mohammad was born in Mecca on the Arabian Peninsula in 570 AD. He was orphaned at an early age and raised by an uncle who was a merchant. There are short segments at the beginning and end of the film where Mohammad is an adult. He leaves Mecca and journeys to Medina where he becomes a prophet.

Storaro made a number of trips to Iran to scout locations and discuss the script with Majidi. He also met with production designer Kreka Miljen Kljakovic, costume designer Shah Ebrahimi and visual effects supervisor Scott E. Anderson. Anderson is an American who won an Academy Award and a BAFTA nomination for Babe in 1995. He earned other Oscar nominations for Starship Troopers in 1997 and Hollow Men in 2000.

“I read the Koran and other books about Mohammad,” Storaro said. “I also found art from that time in history at a museum and in the national library in Tehran. Majid and Mehdi took me to Mashad, a city where there is a sanctuary dedicated to Mohammad. Majid also showed me a fantastic book filled with pictures of paintings by the great Iranian artist Mahmoud Farshchian that really inspired my vision for the film.”

The story takes place during a time when the sun, moon, lightning and fires were the only sources of illumination. Storaro wrote an in-depth description of the visual grammar he envisaged to augment the dialogue and performances. In addition to the realities of available light during that time in history, Storaro planned to use tons of light, darkness, shadows and colours the way writers use words to describe emotions. Majidi embraced his suggestions.

“Colours are like musical notes,” Storaro said. “Different notes have different meanings, depending on the music you surround it with. Every colour has specific wavelengths of energy, which we perceive the same way we feel vibrations.”

"Majid also showed me a fantastic book filled with pictures of paintings by the great Iranian artist Mahmoud Farshchian that really inspired my vision for the film."

- Vittario Storaro AIC, ASC

Mohammad was produced on 35mm film using the Univisium format that Storaro designed and used on previous productions. The Univisium format is designed to make more efficient use of the 35mm frame. Images are composed in 2:1 aspect ratio on three perforation frames. That provides 25 percent more time before the need to reload film magazines. It also trims 25 percent off the raw stock and laboratory costs.

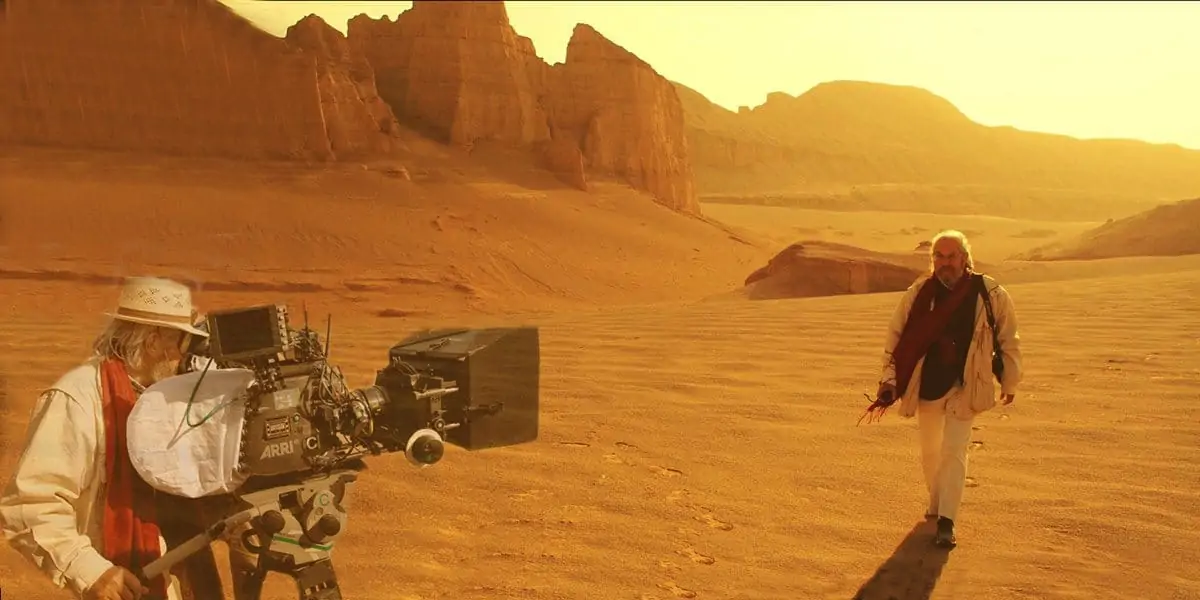

The camera package that Storaro chose for this ambitious endeavour included three ARRI BL 535B cameras, an ARRI Lite for use on a Steadicam, an ARRI 435 for high-speed shots and an ARRI 235 for helicopter shots, along with a complete range of lenses.

The IRIDE company, in Italy, provided lighting equipment, including several light boards with silent dimmers. Grip equipment was provided by Panalight Rome. A 30-foot Super Technocrane was provided by a rental house in the Czech Republic.

Storaro introduced Italian make-up and hair stylists Gianetto and Mirella DeRossi to Majid and Mehdi. He also brought an assistant director, a stunt coordinator, a gaffer with four electricians, a key grip, a Steadicam operator, two camera operators and several camera assistant crew members from Italy to Iran. They were augmented by Iranian camera, lighting and grip crew members.

Production began in early October 2011 at practical locations and on sets built in the ancient cities of Mecca and Medina and in the suburbs of Tehran. Other locations were in Asaloyeh, which is near the Persian gulf, and in the Kalut desert. They recorded rehearsals with a video camera before filming scenes.

Storaro had Kodak Vision colour negative films 5201 (50-speed daylight), 5207 (250-speed daylight), 5213 (200-speed tungsten) and 5219 (500-speed tungsten) in his palette. Scenes were covered from different angles with three cameras.

Two of the crews were Italian and one consisted of natives of Iran. The vast majority of production consisted of day and night exterior scenes. The exposed negative was shipped to the Technicolor laboratory in Rome.

There are no images showing Mohammad’s face. Storaro explained that would be considered idolatry in the Moslem religion. Instead, the audience will see shots from Mohammad’s point of view that were taken with the camera on a Steadicam.

Colorist Nazzareno Neri transferred selected takes of the processed negative to three sets of high-definition digital dailies on DVD files. The dailies were sent to the producer, Majidi and Storaro. Fabrizio Storaro, the visual effects supervisor at the Technicolor laboratory, selected shots and made dailies for the visual effects team.

“Whenever possible, I watched dailies with Majid Majidi and our interpreter, but I usually saw them with my crew on a 65-inch HD screen in my hotel suite,” Storaro said. “That gave us opportunities to discuss ideas for covering scenes in interesting ways.”

There were occasional short breaks in the year-long production schedule for Christian and Islamic religious holidays. The final scenes were filmed on October 26, 2012. Storaro estimates that approximately a half a million feet of film was exposed.

When we asked Storaro if shooting Mohammad was an unique experience, he reminded us that he addressed that issue while discussing his experiences collaborating with Bertolucci on the production of Little Buddha in 1993.

“Shooting any film is a life experience,” he said. “Some experiences are more important than others, because it adds to our knowledge of the world we live in. Every day of shooting is a lesson in life. I was lucky to have many wonderful experiences, which have enlarged my vision of the meaning of our journey as human beings.”

Post-production for Mohammad will be done at the Technicolor laboratory in Rome. Visual effects scenes will be timed in a digital intermediate suite and recorded out to film. The vast majority of Mohammad consists of live action cinematography, which will be timed in analogue format in collaboration with colorist Angelo Francavilla.

Noor Ahmed Productions plans to release Mohammad with Iranian language dialogue. Release prints in major European countries will have dubbed sound tracks. Other international distribution will have sub-titles. The release dates haven’t been set.