IN HONOUR OF ART AND ENGINEERING

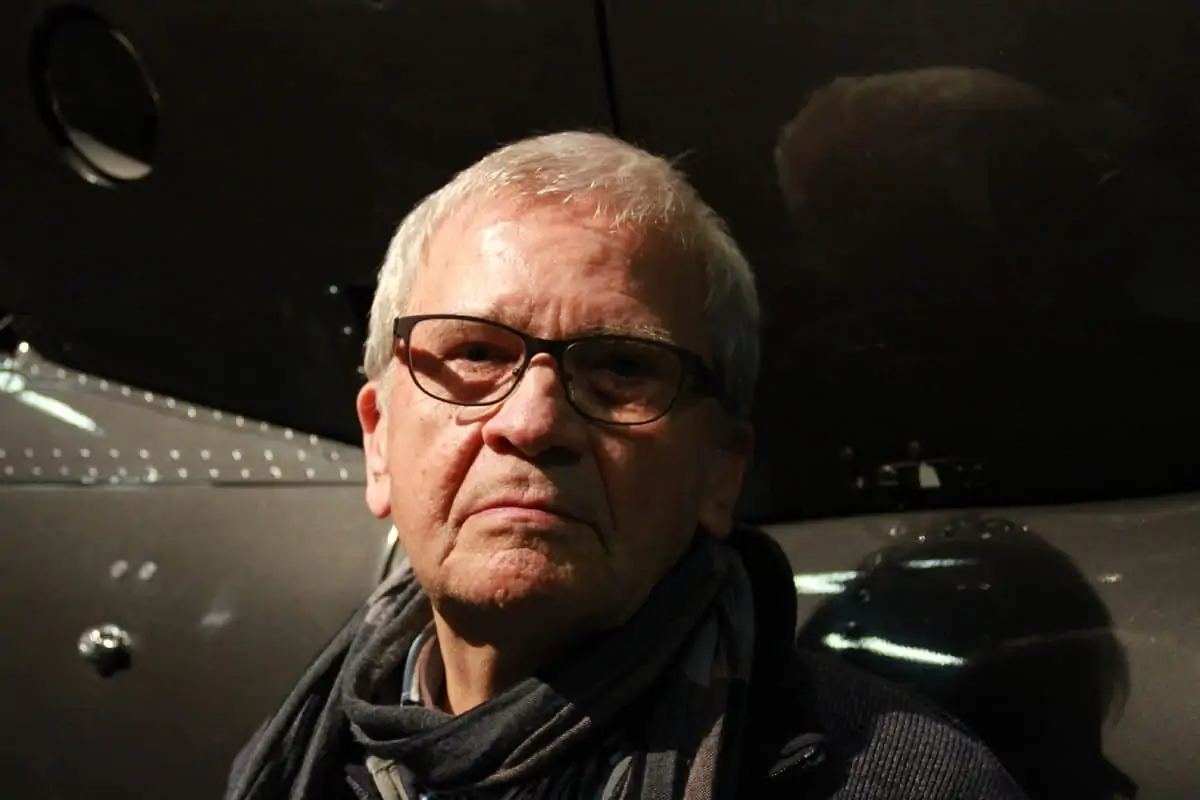

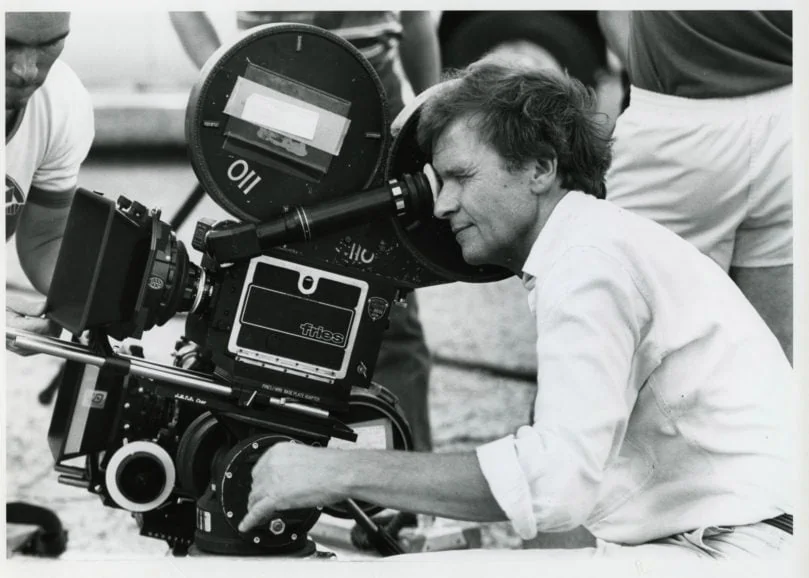

For his outstanding body of work, serial camera inventions and unrelenting fight for better recognition and fair remuneration of cinematographers everywhere, Jost Vacano ASC BVK is a deserved recipient of Camerimage’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

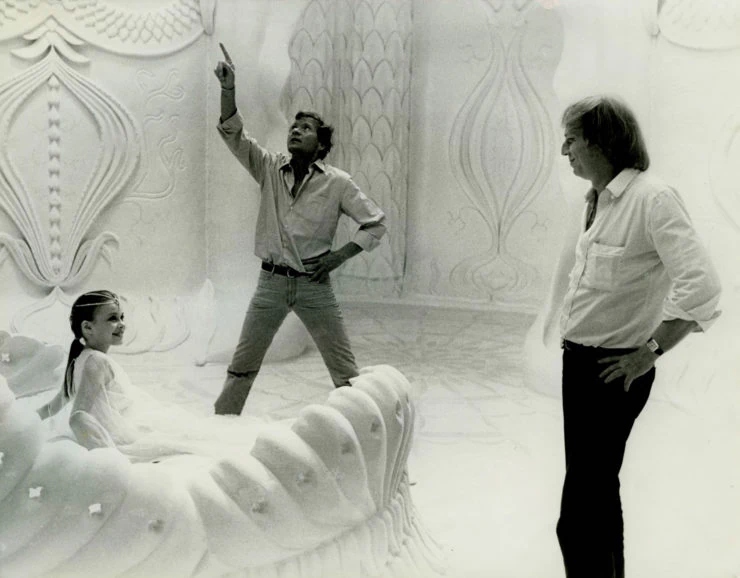

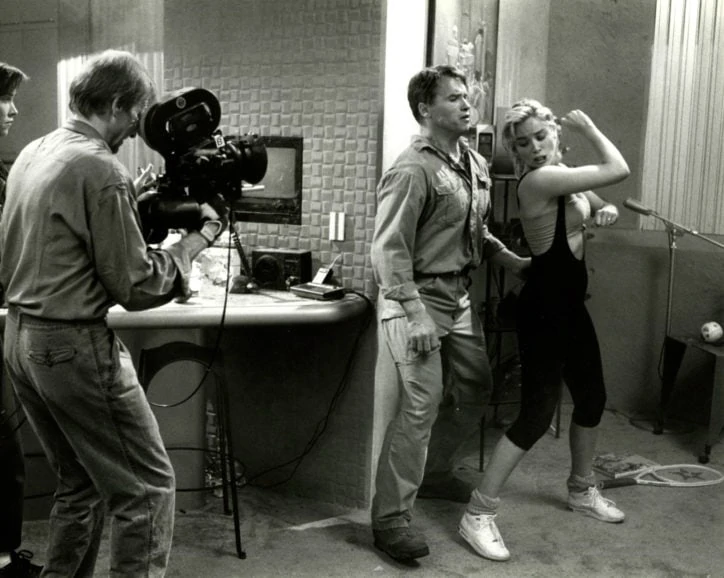

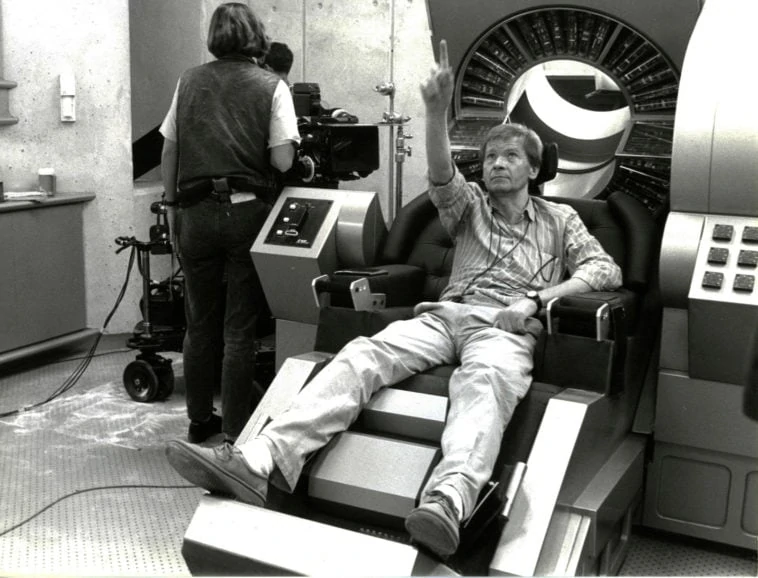

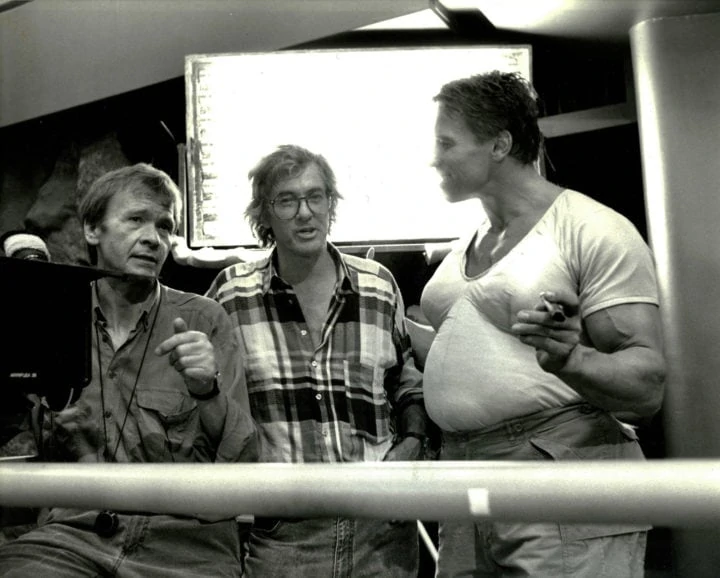

Best known for his Oscar-nominated Das Boot, German DP Jost Vacano ASC BVK also enjoyed a two-decade collaboration with Paul Verhoeven, which included creating a futuristic colony on Mars in Total Recall, dystopian Detroit (shot in Dallas) for RoboCop, as well as Starship Troopers, Hollow Man and Showgirls.

Born in 1934 in Osnabrück, the son of a choreographer and a conductor, Vacano describes himself as a “visually oriented person” whose hobbies included stills photography. He began making films with an 8mm camera as a schoolboy.

“I felt that stills were static and that, for me, the image should be moving,” he says. It’s a kineticism that defined his later work.

Login to continue reading

This content is exclusively for digital magazine subscribers.

Start your subscription today, or login below to continue.

Practical film school

Intent on a career behind the camera, Vacano settled in Munich after leaving school. The city was the centre of filmmaking in Germany in the 1950s but lacked a film school. There were schools in Poland, Paris, and Moscow but all depended on a student speaking the local language. Vacano knew he’d have to learn the trade by getting involved at grassroots.

“I was very naïve and was an active moviegoer and knew the names of several cinematographers working in Germany. I thought I’d try to talk to them and ask to join their crew.”

He made phone calls but was told time and again that in order to get a job, even work experience, he would need a showreel. Catch-22 but Vacano’s persistence was undimmed. Since he could neither study cinematography somewhere, nor had a chance to learn and work in a professional camera team, he had to start as a complete autodidact.

“I thought I’d go to high school and study something similar to cinematography – like electrical engineering. At the same I knew I wanted to be a cinematographer not an engineer, so I also enlisted in an acting school. This was not to become an actor, but to learn the basics of acting so that later on I’d know how to work with actors.”

He wasn’t the only one with that idea. Also at the Munich school was Peter Schamoni, an aspiring director who, like Vacano, had struggled to break into the industry. The two were to form a lifelong friendship.

Together, they gained permits to cross the Iron Curtain from West Germany into Moscow in 1957 and make a documentary about the World Youth Festival. They spent a week there during which, with a rented 16mm Bolex, Vacano captured the crowds and celebrations of the official communist party display alongside shots of poor Muscovites in the suburbs. Jazz im Kreml and Moskau ruft! (both released in 1959) were his first as cinematographer.

More documentaries, commercials and TV films followed as Vacano learned on the job before making his cinema debut with Schonzeit für Füchse, (No Shooting Time for Foxes), again with Schamoni, which won the Silver Bear in Berlin in 1966. His career took off in the mid-1970s when he shot The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum by Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta and later Lieb Vaterland Magst Ruhig Sein with Roland Klick. Vacano was honoured for both films with the Federal Film Prize.

Mobilising the camera

All the time, Vacano was marrying artistry with engineering skills. While Garrett Brown was experimenting with what was to become Steadicam in the US, Vacano was making his own explorations of gyro-stabilised camera systems.

“To me, film is always about movement. I have to involve the audience in what is happening, becoming part of the scene, not just show them. Moviegoers don’t necessarily want to sit on a tripod or glide on a dolly. Sometimes the camera has to be like a living person in the scene.”

He first worked with a Naval device for keeping binoculars steady on ship and deployed it for crime drama Supermarket (1974) directed by Roland Klick. “I got hold of this stabiliser and connected it to a Arriflex 2C 35mm which reduced shake and created a feeling of the camera - and by this, the audience – become part of the action.”

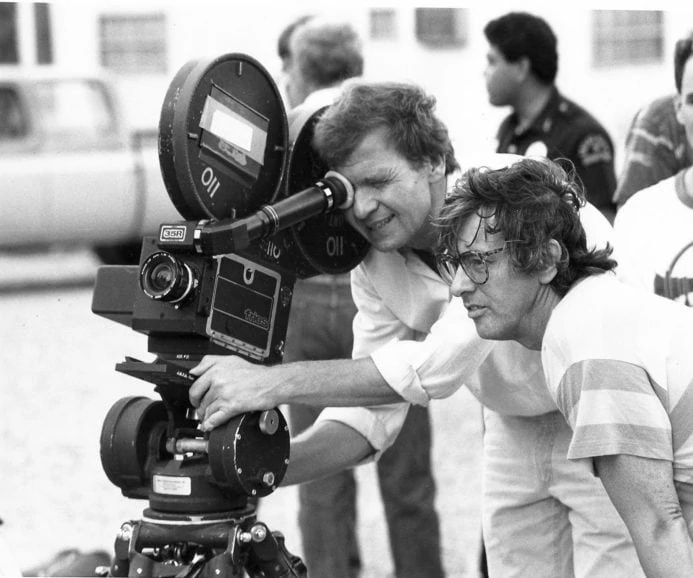

He refined it to ground-breaking effect to put the viewer inside the claustrophobic submarine of Das Boot (1981). Director Wolfgang Petersen wanted to tell the story – adapted from Lothar-Günther Buchheim’s bestseller – with as much authenticity as possible and had 1:1 interior replicas of a U-boat constructed for the shoot.

“We couldn’t use a Steadicam because it was too big to fit through the connecting doors,” Vacano says. His instrument had two gyroscopes to provide stability for the Arriflex, a different and smaller scale solution than Steadicam, and on which 90 percent of Das Boot was shot. It became known as ‘JostiCam’.

“The story is told through the eyes of a young war correspondent, so we wanted to put the audience in his point of view. The producers were under pressure to make the film for the worldwide market and to show that German filmmaking was as good as Hollywood.”

Several directors including John Sturges and stars like Robert Redford and Paul Newman had been lined up long before to film a version of Buchheim’s book in Hollywood. Sets were even built but script problems scuppered production.

Making Das Boot

“We had no experience shooting a submarine film. That type of film had all been done before in Hollywood (such as The Enemy Below, 1957). My idea was to shoot it like a documentary, handheld and without film lighting, to get across the experience of what it was like being in that tight and dangerous space in wartime.”

With no external light available, Vacano fitted the sub’s interior with marine lights which accentuated the pale skins of men confined for weeks below decks. The mocked-up sub was on a hydraulic platform at Bavaria Studios, but Vacano needed a solution for keeping his camera steady even while the floor rocked in all directions.

“People couldn’t see the horizon in the submarine and had no orientation at all, therefore I needed to stabilise the handheld camera on the horizontal line, so I used a spirit level at the beginning of each take to orientate the three axes of the stabiliser.”

With barely room for a camera-op let alone focus puller, Vacano also devised a remote focus control using bowden-cables, a pulley system, and a ring around the lens for the focus puller to adjust just behind or underneath him. It’s a piece of electronic kit today’s DPs take for granted.

The film’s producers took some convincing, but they had the courage to back the project with a budget of $18.5m, making it among the most expensive in German cinema. It repaid spectacularly when it reaped $84.9 million worldwide (equivalent to $220 million in 2020) and six Academy Award nominations, including for its cinematography.

“My instinct, whenever I have a problem is ‘can I build it myself?’. Now these tools are easy to use. In 1980, it was like having a Black & Decker on set.”

The success of Das Boot and Vacano’s new standing as the first German to be Oscar nominated for cinematography set in train a struggle for professional recognition that is still unwinding.

Campaigning for copyright

“The prevailing view was that cameras were technical devices and the cinematographer just a technician who pressed a button when the director called action,” he says. “Technicians are paid a flat rate and that’s the end of the matter. I believed that the cinematographer is not just an author of the image but a key decision maker in the film as artform. I also believed I’d proved this with Das Boot. I decided to campaign to ensure that we are perceived as image creators and that this is also reflected in copyright law. It became my second profession.”

It has taken 40 years and a series of lawsuits (challenging production company Bavaria Film, public broadcaster WDR which serialized Das Boot and distributor Eurovideo) but, in Germany at least, the work of a cinematographer is recognised by law as one of the co-authors of a film and able to claim a percentage of its turnover.

Having sunk his own saving into the legal challenge, Vacano was finally recompensed in 2019. “It was a professional-political campaign. The fact that not only cameramen, but also editors and costume designers – everyone involved in a film – should be entitled to share in its financial success, was the goal.”

Total Recall

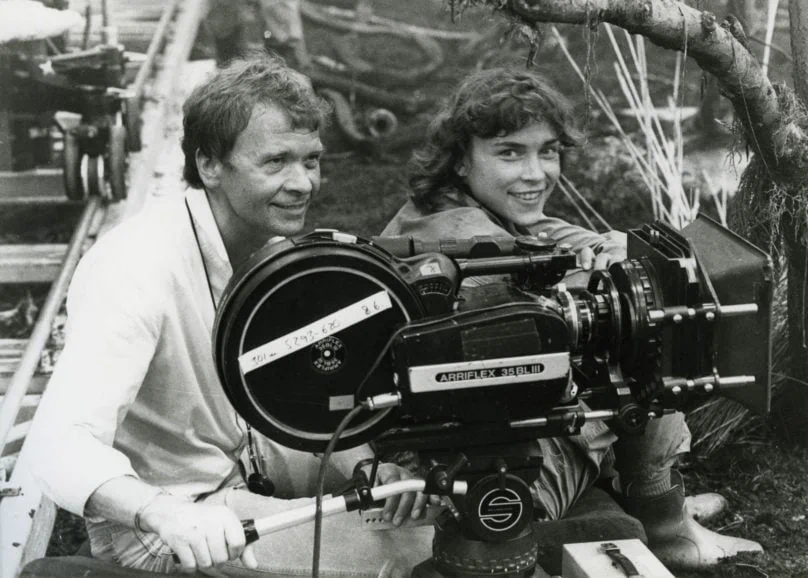

Since 1986, Vacano has worked primarily in the US, collaborating with Verhoeven, with whom he previously made World War II-resistance drama Soldier of Orange, followed by the controversial coming-of-age film Spetters.

Filming sci-fi blockbuster Total Recall at Mexico City’s Churubusco Studio, Vacano struggled to find the right colour red for Mars.

“Every DP, every gaffer, has these nice little swatch books and you go through them and say, ‘This is a wonderful colour.’ You do a film test and it looks great. It was two weeks before shooting and I just figured we would order what we needed – two hundred or three hundred rolls – it was a huge amount. Then we found out the colour we chose wasn’t in production anymore. I tried to substitute with another colour from another company, but the film tests didn’t work. Finally, Rosco agreed to manufacture it for us, and they started production of this special colour again. Just barely in time, we got what we needed.”

Filming Verhoeven’s Hollow Man, Vacano was challenged to execute the lighting of invisibility. “For a director of photography, that presents an interesting challenge, because cinematographers are normally hired to shoot things we are supposed to be able to see. In CGI-effects films, you usually shoot something that is not yet there, like the bugs in Starship Troopers; but in Hollow Man, we shot something already there that was supposed to not be there.”

Of Verhoeven he says, “The way you want to create images and tell your story is about personality and you need a director working the same way you are working. Paul and I were like that.”

That wasn’t quite the case on Katharina Blum. “There is some great acting, and its themes matched the political situation at that time but the director and I did not fit together well. We were both professionals and certainly did the best we could, but it was not an altogether happy experience.”

Art, engineering, and authorship

Das Boot excepted, Supermarket perhaps best showcases Vacano’s style. He enjoyed a “wonderful relationship” with Klick to stage scenes collaboratively on location around Hamburg and the director was also open to more technical ingenuity from his DP.

“We had a very low budget and shot 100ASA film but with a lot of night exteriors. There were no high-speed lenses available, and we didn’t have the money to spend on HMIs and giant film lights, so I thought I’d have to build a faster lens.”

He took an Olympus 1.4 speed lens to shoot with available light and rehoused it to fit on a 52mm ARRI mount. “The lens was much bigger than the camera mount so I took all the glass elements out and built a new housing with no iris diaphragm, just wide open with no stops, so we could shoot all the night work. It was a mix of art and engineering.”

And here is Vacano’s creed, his fierce defence of the role of the DP.

“Cinematography in general is about lighting, composition, and movement of each shot,” he says. “That doesn’t change with postproduction of VFX or with virtual production shooting against video screens. The DP is still ‘directing’ the photography, setting the creative photographic standards. I’m not denying anyone else’s artistic influence, or the high degree of responsibility for the scenes they have created. But I think, the photographic creation of an entire film, in its totality, is a unique piece of art. This cannot be divided, it has only one author: the Director of Photography.”