The Russian cameraman and filmmaker Victor Kossakovsky is known for his poetic and visually powerful documentaries ¡Vivan las Antipodas! and Aquarela. His black and white silent film Gunda takes us back to the origins of filmmaking. For Joaquin Phoenix, executive producer, it’s a film of profound importance and artistry. Birgit Heidsiek spoke with Victor Kossakovsky about his visual approach, the challenges he faced, and his fascination with 96 fps.

Is it true that you shot one of your early films through the window of an apartment in St. Petersburg?

It happened accidentally. In 2000, I was in Germany where I wanted to shoot a comedy. During that period, I returned to Russia five or six times, where I shot personal footage from the window of my apartment. After a year of waiting around in Germany, I realised that I didn’t have money for the comedy, but I did have great footage for a comedy which I ended up shooting from my window.

What made you decide to become a cameraman?

I always wanted to be a cameraman. I spent my entire childhood using a photo camera to film butterflies, flowers, fishes, birds, and landscapes. I started taking photos at the age of six or seven. It was a privilege. My uncle gave me his photo camera and at age of 12, children can take summer jobs when school is out. I got a job in a factory that produced motor bikes and earned enough money to buy a 500mm lens for my camera.

Did you dream of a career as film director?

I never wanted to be a director. The camera is essential for cinema. It makes a film, but not the story. I don’t believe in films that tell stories; I believe in films that show something. If people want to tell a story, they can write a book. I don’t believe in storytelling. Cinema should not tell a story; it should show us something instead.

What does cinema mean for you?

In Russia, we watch films in movie theatres — not on TV, not on computers. We have two main film schools, and each of them has great cinema projection. While I was studying scriptwriting and directing in Moscow, I watched films four or five films a day on the big screen. This is a privilege that education affords. Today in Europe, you can’t find anything like it.

Where did you start your career in the film industry?

I worked as a camera assistant for the best Russian cameramen in the Leningrad-based documentary film studios for a few years. I directed my first film by accident. I got access to a great philosopher but I was not allowed to bring an entire film crew to assist me so I started shooting. I showed the footage to directors so I could turn it into a movie. They suggested that I edit the footage myself because I had also worked as a professional editor for five years. I was afraid to present footage myself, so I called Georgi Rerberg, the cameraman who shot Mirror by Andrei Tarkovsky. I showed him my footage and he liked it and said, “I’ll go with you.” He shot the main episode of my first movie.

Do you always shoot your films yourself?

After working with Rerberg, I was unable to find anyone who could shoot my films as well as he did. So I ended up being the cameraman on most of my films. However, Gunda I made with Egil Håskjold Larson from Norway; he’s a great Steadicam operator. I saw his movie 69 Minutes of 86 Days – a documentary about a refugee family travelling from Syria to Sweden over the course of 69 days. He was following a family — and he paid particular attention to a three-year-old girl — with the Steadicam. He was so professional, so profound in his understanding of movement and the distance between the camera and the subject. The most important aspect of camera work is to find the right distance between camera and the subject. It was brilliant Steadicam work. For Gunda, I had to film animals closely and I had to move with them, therefore I needed a Steadicam operator.

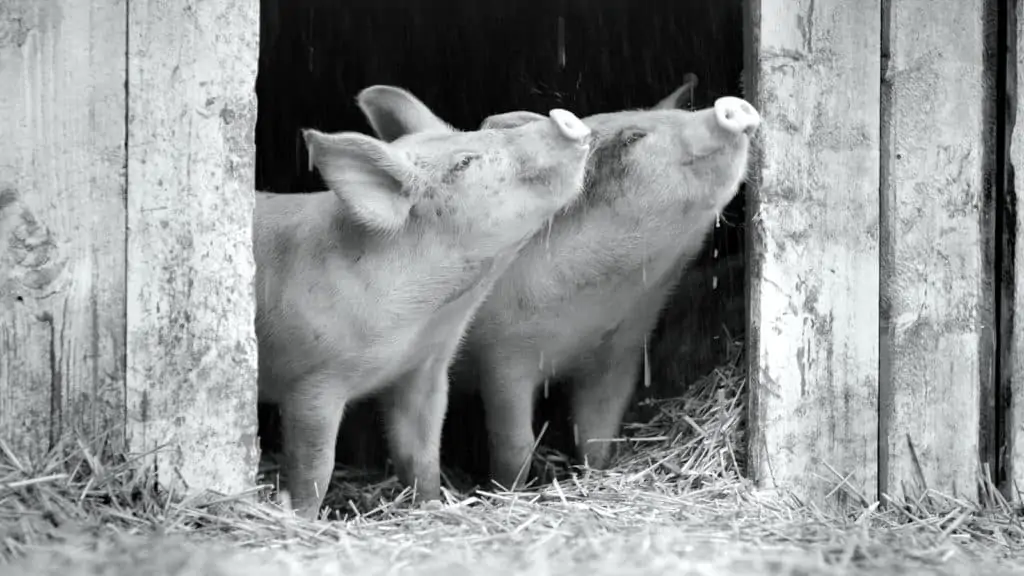

How did you start Gunda?

It started with finding the right actors. Normally, it takes a lot of time to discover the heart of my film. In this case, it was easy. We met Gunda on the very first day of our research. I opened the door to the pigsty, and Gunda came towards me. She was cinematic — powerful. Her look was strong. So I told my producer Anita Rehoff Larsen, “we’ve found our Meryl Streep!”

What kind of visual concept did you choose?

I studied the sty where she lived, so we designed the set to be identical to her home but with a 360-degree slot to shoot through. We put dolly tracks around the sty. We were outside, but the lens was inside and the slot was just big enough for the lens. Wherever she was, we were just able to follow her. We didn’t disturb her because only the lens was inside, while the camera and the crew were outside. She was also gentle with us, and so friendly — even at the moment she gave birth, she was comfortable with us. She was a dream character.

What kind of equipment did you use?

We used the ARRI Alexa-Mini, which is convenient and easy to use for this kind of documentary. It’s really fast and small. We used an Angénieux 24–190 zoom lens. We used some lighting, but very little so we wouldn’t disturb her. It was practically unnoticeable. The pigsty had a lot of dark corners, so we made some little additions to light these areas. We used a disco ball light for these dark areas. Normally, a disco ball light rotates, which is why it creates its unique effects. But we didn’t move it, so it lit the entire sty. Wherever she went, she eventually came into the light.

We didn’t know where the piglets would go and there were so many of them. You can’t light everything because that would destroy the look. But these little spots of light looked natural because there were holes in the roof, so it looked as though the sunlight coming through the roof was lighting the sty.

Why did you decide to shoot the film in black and white?

We made the decision to shoot in black and white for a similar reason. It brought me back to the birth of cinema. Another consideration was that, depending on the circumstances, colour can be overwhelming. If you see blood in colour, it is too naturalistic and your attention wanders. Often, lush colours make us focus on different things, such as the background. I didn’t want to show cute pink piglets — and believe me, they really are cute. I didn’t want to seduce the audience this way. I felt that black and white would make us focus on their being instead of on their appearance.

At the end of the film, we see Gunda looking for her piglets, who are gone. How often does this happen to a pig?

Twice a year. Piglets normally live between two and six months and then they are slaughtered for food. This is what we do. But Gunda lives in privileged conditions compared to other pigs – at least she enjoys freedom. It is very good in Norway. Ninety per cent of the pigs in factory farms have no chance to dig; they spend their whole lives on a concrete floor in a small cage.

Don’t farmers see animals as living beings?

I hope that people will face the fact that we are cruel. At the moment, we are living on a planet with seven billion people. We have one billion pigs living in cages, 1.5 billion cows living in horrible conditions and 50 billion chickens that live in cages all their lives. We have to face up to it; we have to stop doing this.

Do you want to open people’s eyes?

Documentary cinema is a great tool to show the realities of the world, to show things that we do not see, that we perhaps don’t want to see or that we have collectively agreed that we don’t want to see, so we allow ourselves the privilege of not thinking about them. With Gunda, we want people to see these animals as sentient beings and we want to encourage them to consider the possibility of their consciousness and selfhood. Gunda is the most personal and the most important film I have ever made.

Gunda is quite the opposite of your previous film Aquarela. Do you like to shoot films that look different from one another?

I like to use a different style with each new film. I like to challenge myself and I don’t want to repeat myself. If I had to do that, I would quit. I started Gunda at the same time as Aquarela because I wasn’t sure if there was a market for 96 fps. There is no market yet, but now I will continue making movies at 96 fps, I will not go back. I don’t know why filmmakers — and especially cameramen — don’t understand that there is no point in filming at 24 fps. We aren’t restricted any longer to a 10-minute roll of film in a big bulky magazine. We have no limit. At 96 fps, we can see emotions play across a face, and we can even see fast, subtle movements, which would otherwise have been blurred. I noticed this when I was making a short film about a ballet dancer who was very emotional when dancing. But I couldn’t see her facial expressions at 24 fps; they were just a blur. So I started to experiment and then I noticed that when I went to 48 fps or 96 fps, I began to see the emotion on her face.

Of course, we need the correct speed in projection, but if you can shoot at 96 fps, then you can project at 96 fps. I don’t understand why it’s not done. Cameramen are the ones who revolutionise cinema, not filmmakers. It is time to change. We have colour, we have sound, stereo sound and Dolby Atmos sound. We have digital and we have to move forward because 24 fps is over and done with.

Do you consider digital filmmaking to be an advantage?

Of course. You can’t compare digital with the previous technology. Many things are simply impossible without digital. When we filmed Gunda, we didn’t know when she was going to give birth. For situations like this, the pre-recording feature in the camera was great. We didn’t have to keep the camera rolling all the time in order to capture the first seconds of her giving birth. The camera was pre-recording but not recording – it pre-records 30 seconds. This is a revolutionary tool.

What was your shooting ratio?

We didn’t film much for Gunda. We were lucky to shoot only 4:1; it was like old-school cinema. It was like the old days when we shot 35mm. We filmed a total of only about six hours of footage.

What is your next film going to be?

My next film is a comedy called Architecton which is about building a futuristic city. As for the camera work, it will be revolutionary. It will be funny but it will also be a surprising utopian vision.