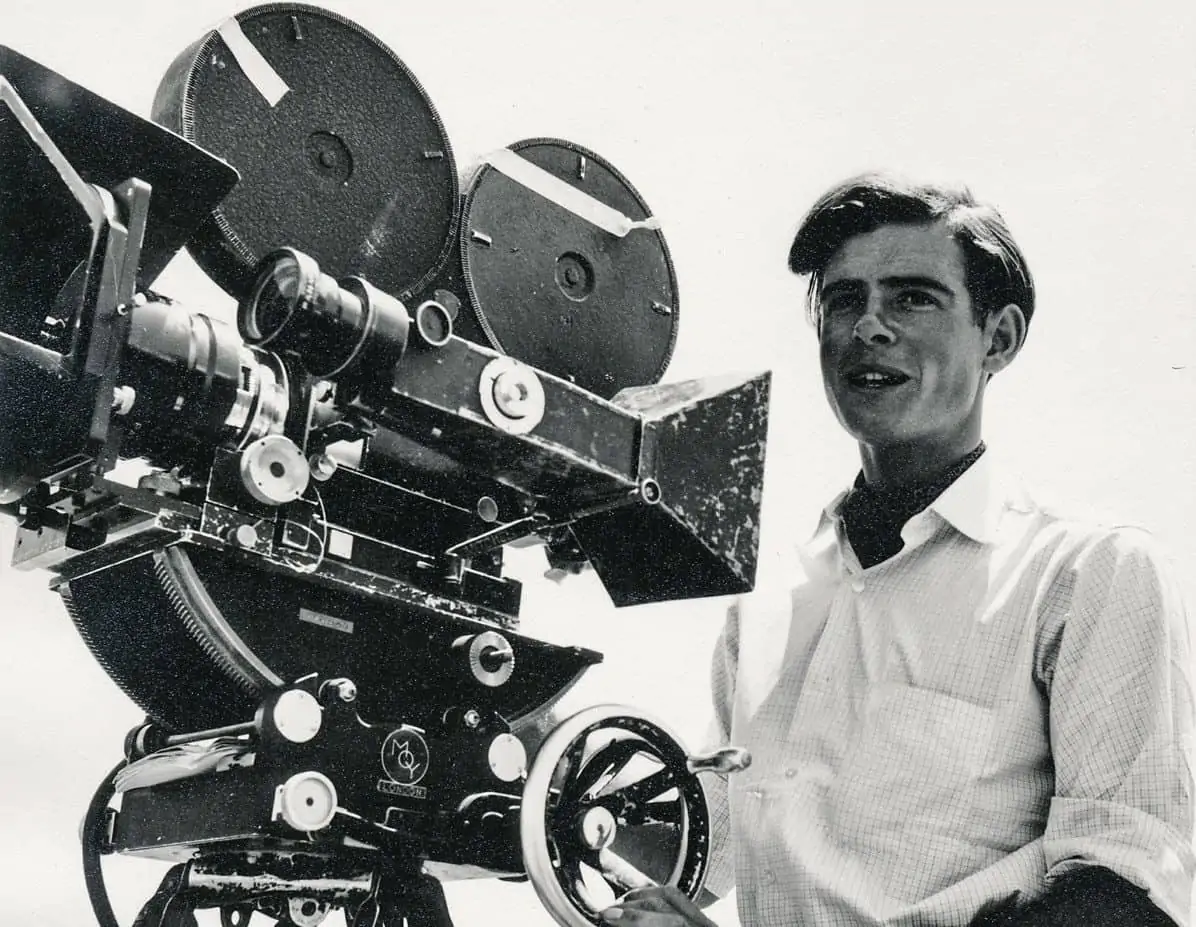

Lead image: Kevin Brari and 1st AC Lukas Fahnert shooting Lost in Time. (Photo: Steffen Schmitz)

LENSES WITH CHARACTER

Unusual bokeh, interesting flares, aberrations at the edges of frame – these are some of the artefacts which lens manufacturers once strove to suppress, but which are now prized by filmmakers seeking a unique look. Five DPs discuss the reasons, both creative and technical, behind their glass choices.

Since digital cinematography became the norm, many DPs have chosen to offset the crisp electronic images with “characterful” glass, but of course, the idea of selecting unusual lenses for their aesthetics is far from new. “Probably the most original idea for alternative lenses was on The Charge of the Light Brigade, photographed by David Watkin [BSC],” says Robin Browne BSC, who served as focus puller on the 1968 production.

Watkin, who passed away in 2008, paired an anamorphic lens with uncoated Ross Ensign glass from the 1930s. “Light refraction would occur within the elements of the lens itself,” he says. “[They] were constantly alive, giving rise sometimes to the most wonderful accidents. And accidents (of the right sort) are always the best things in photography.”

“An anamorphic lens was backed up to the Ross lens,” Browne recalls. “The big problem was setting the stop, which was deep in the [specially adapted] lens mount. Sometimes one had to remove the lens to set the stop. Often David would preset the stop and control exposure with NDs or by the shutter. Light leak was a problem, so the gap between the two lenses had to be covered.”

Over half a century later, filmmakers are still exploring the benefits of combining stills glass with anamorphic adapters. Young German cinematographer Kevin Brari paired a Kowa 8Z anamorphic with a number of carefully selected taking lenses for the post-apocalyptic Lost in Time, shot on the Blackmagic Ursa Mini 4.6K.

“I really felt that the film needed the detail and structure that anamorphic lenses provide,” says Brari, “but I wanted to contrast it in an impressionistic way.” With 40mm Voigtländer, 58mm Helios 44-2, and 50mm and 90mm Leica R lenses he found “the deep warmth and organic feeling” he was looking for.

“What I loved most about it was the modularity of the setup,” Brari reflects. “As there are two separate parts, the taking lens and the anamorphot, each with a unique characteristic, it opens up a wide range of beautiful and truly unique looks depending on your choices. I tested several vintage lenses and coatings and really loved the journey and all the imperfections that you rarely see with modern lenses.”

I’m often drawn to anamorphic lenses when shooting digitally, as the bokeh lends so much depth to the image.

Nanu Segal BSC

Imperfections were important to Nanu Segal BSC when she determined the look for the Film Four feature Old Boys, set in an English boarding school. “Touchstones for Old Boys included films from the ‘60s such as The Loneliness of The Long Distance Runner, If… and Kes, which were framed 1.66:1 and shot spherically on film. We wanted to recall the organic beauty of that period of filmmaking,” says Segal, “but we had to shoot digitally with the Alexa XT. We tested an array of lenses, both modern and vintage, as well as spherical and anamorphic. The Hawk C Series, with their specific circular bokeh and aberrations towards the frame edges at wider stops, felt like they gave us the texture we were looking for.”

Segal has embraced anamorphic lens flares on a number of projects, though wary that they can be easily overused. “Because they vary so much from lens set to lens set, it means that the use of flares is a really exciting part of my tool kit as a cinematographer. The addition of a flare can totally transform the feeling of a shot, particularly when shooting handheld, where a tiny movement in the position of the operator (usually me) can add or delete the light streaming down the lens. Sometimes I’ll just use the edge of a flare as a way to push light into the shadows, if the image feels too heavy. This can be a more natural way to lift the shot than adding in fill light.”

For the short film Bit by Bit, directed by Juliet Ellis, nighttime vistas of Sheffield were an important driver of Segal’s lens choice. “I’m often drawn to anamorphic lenses when shooting digitally,” she admits, “as the bokeh lends so much depth to the image. However, Bit by Bit was shot spherically on T1.3 Zeiss Superspeeds because I wanted to shoot at faster stops than anamorphic lenses allow; this meant we could embrace the available light of the Sheffield cityscape at night. The circular bokeh of the spherical lenses captured the cityscape in a very direct and unsentimental way, which felt right for this particular story.”

While Superspeeds are popular for their wide maximum aperture, sometimes the minimum aperture is a lens’s critical attribute. Years after The Charge of the Light Brigade, Browne employed medium format Hasselblad glass when he worked as SFX DP on films like Krull, Moonraker and A Passage to India. “Hasselblad lenses have small stops – f/22, f/32, even f/64,” he notes. “These stops and the range of extension tubes or bellows enable extreme close-up and good depth of focus.”

A large of depth of field facilitated effects such as compositing mattes. “I had a mount which enabled me to track the lens left and right or up and down to accurately line up matte shots by moving the image in different directions,” Browne adds. The large image circle of the Hasselblad stills glass ensured coverage of the VistaVision 8-perf 35mm format used in pre-digital VFX work.

Tristan Oliver BSC found himself in the opposite position for Wes Anderson’s animation Fantastic Mr. Fox; he needed to mount cinema glass on a stills camera. “When we started using digital stills cameras for stop-frame feature work, we were unable to source decent full-frame zooms to fit on the Nikon camera bodies,” he explains.

Oliver used a 1.6x teleconverter and a custom extension tube to mount a Cooke 20-100mm T3.1 Varotal, a lens favoured by Stanley Kubrick, on a Nikon D3. “My main reason for using this lens is that it was, at the time, somewhat in the doldrums. It wasn’t quite ‘fashionable’ again and they could be picked up relatively cheaply. They have decent close focus and custom bayonet-fit dioptres which clipped onto three tiny bolts on the front, which made them useful for the macro stuff I tend to do.

“I should stress these were not my everyday lens. Obviously as a relatively old-style piece of glass designed for film, there were some chromatic and spherical aberration issues, but given Wes’s very central framing style, these were mostly ameliorated and actually helped focus the interest on the middle of the frame.”

David Lanzenberg encountered a similar issue when he shot the pilot of You for Netflix, having selected Todd AO anamorphics, which have significant focus fall-off at the edges. “It was difficult for the operators on that show to become less traditional,” he says of the central framing required to keep the subject in the sweet spot. “We had to say, ‘If you pan left, we won’t get a call from the studio, because their eyes are sharp!’”

We had a first rendition of the [Ultragold] lenses, and we were like, ‘That’s great, but let’s go further.’ We wanted the ‘Alice in Wonderland tripping on acid’ version!

DP David Lanzenberg

Lanzenberg’s next project, the first two episodes of Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, saw him risking Netflix’s ire again. “We definitely wanted to give it some teeth,” he says of himself and director Lee Toland Krieger, who perhaps sought to distance his dramatic 2018 adaptation of the Archie comic from the earlier, campy sitcom, Sabrina the Teenage Witch. “We wanted some specific lenses that would give that feeling of something’s about to happen, a sense of unease.”

It was Panavision who suggested Ultragolds, a very rare series of T1.4 anamorphics. “They were very, very delicate and precious lenses, very big pieces of glass. The object itself was gorgeous to look at,” Lanzenberg enthuses.

Panavision’s Guy McVicker and Dan Sasaki customised the Ultragolds to the filmmakers’ requirements. “We had a first rendition of the lenses, and we were like, ‘That’s great, but let’s go further.’ We wanted the ‘Alice in Wonderland tripping on acid’ version!” Lanzenberg remembers jumping with excitement when he saw the revised results, comparing the look to “a Francis Bacon painting. The background was just melting away.”

He and Krieger used more conventional G Series anamorphics for “normal” scenes, switching to the Ultragolds whenever Sabrina encounters the supernatural. The extreme look of the rare glass was loved by some and hated by others. “I think the studio was very upset with us,” Lanzenberg confesses, but Panavision experienced a wave of demand from DPs asking for “the Sabrina lenses”. Lanzenberg has no regrets. For him, choosing a lens with character is about “giving a unique stamp, whether it be on a pilot or a movie. It’s hard to do it with cameras these days, because a lot of the streamers have their own [requirements] for resolution and so forth, but definitely with lenses it’s really giving [a show] its own authentic tone and look.”