REALISING THE VISION

Tania Hoser speaks to three fellow members of illuminatrix – a collective of female cinematographers – about their planning and process when creating visual concepts for a film and turning them into a cinematic reality.

For me, one of the most beneficial aspects of being part of illuminatrix is the opportunity to share know-how with other female directors of photography who have at least five years’ professional experience. Discussing the development and realisation of visual concepts it becomes clear that whilst the journey is different for all of us, our routes have a lot in common.

“I read the script and then put together a collection of images. The images may be screengrabs or come from fine arts photojournalism, they may just symbolise part of an idea or feeling, or if can’t find an actual image I write down my thoughts. They accumulate into something abstract at first, which I then sort by theme, colour or emotion until a visual language starts to emerge,” says Petra Korner AAC.

By the beginning of pre-production, Korner will have created a large PDF file that is still a visual brainstorm, but which she uses to communicate her intentions. It becomes the basis for developing and refining visual concepts with the director, and subsequently the other department heads.

When cinematographer Sara Deane reads a script, she gives it time to percolate and then finds ideas form naturally as pictures. “I might have a really strong image in my head and then have to find elements of that in other images. There may be something about one picture and something about another that build up to what I have in mind. The visuals should ideally be going on a journey with the character and the story arcs.”

I go beyond the visual references, I also talk to the director about how the project came about, why they are attached or why it was written and what they are considering editorially and music wise.

Ashley Barron ACS

WORKING WITH THE DIRECTOR

Speaking about short film Stand Still, directed by Isabella Wing-Davey, Ashley Barron ACS says: “We prepped thoroughly so the visual concepts became part of our DNA and we could just execute the plan on set. We worked really fast – I barely needed to speak to Isabella on set, it was like using muscle memory informed by preparation.”

When Barron looks at visual references with the director, she finds out what they like and dislike. “It is important to figure out what not to do as much as what to do. The more I can get into the director’s head, the more I can work intuitively for them and the project when things get tight.

“I go beyond the visual references, I also talk to the director about how the project came about, why they are attached or why it was written and what they are considering editorially and music wise. I also want to get to know the director’s ethos and our compatibility as human beings to know how we can be sympatico on the journey together.”

Deane spends lots of time with director, finding visuals they both like and identifying what it is about that image or moment from a scene that is really working for them. “Is it because the characters were looked at objectively or subjectively? Was the camera at a slightly lower or slightly higher angle? What is the camera’s connection to the character and is it helped by the background being in focus or out of focus for example?”

Especially at the start of my career, when narrowing down ideas and after talking with the director about why we liked reference shots or scenes, I would then spend time looking at the photographic and compositional elements such as screen space, screen direction, and headroom until I had a clear guide about how these would be used in our production. Currently, working mainly in documentary, as well as understanding the project and the director’s approach, prior to the shoot we talk about the core story and the most appropriate way to cover the scenes so I can work intuitively with them on set.

During prep, there is ‘elimination by examination’ as we discover what is important, says Korner. In the script for her current production four-part mini-series The Holiday – a psychological family dynamic thriller in an exotic holiday destination – the characters stay in an opulent old villa, which is supposed to make them uncomfortable.

“However, after looking at countless locations, we realised that a modern, sterile villa conveys their discomfort better visually and in turn affects our framing, lens and lighting choices,” she says. “I don’t find it useful to create a lighting list before I have seen the locations. If we don’t have the budget or manpower to do something properly, I would rather find another approach.”

For Deane, a lot of it comes from recces: “When you go in a space or get set designs then you start to see what you can add or how you may amend your imagined idea into something that becomes more solid so that by the time you are shooting you have probably shot the scene a minimum of 10 times in your head.”

It’s important not to fall into a pattern of a handy focal length, favourite aspect ratio, lenses or LUT that you use on every shoot.

Petra Korner AAC

MAKING CHOICES

When making choices, Barron thinks about the story or style and also about logistics. “You have to think not only about how to achieve the visuals technically but also make sure your kit fits your crew size and is safe too. I have a solutions-based approach and can usually find a way to achieve what we want to do. Only if there is no other way to do it do I ask for additional kit. I’m careful to pick my battles though and usually manage to balance the cost of what we need by making savings elsewhere.”

Sometimes it is straightforward to get from your references and recce to a kit list, she adds: “If you have referenced, for example, enough anamorphic movies then anamorphic is the way to go; but the choices must be for story reasons.”

Korner makes sure that everything she chooses is for the particular production she is currently working on. “It’s important not to fall into a pattern of a handy focal length, favourite aspect ratio, lenses or LUT that you use on every shoot.”

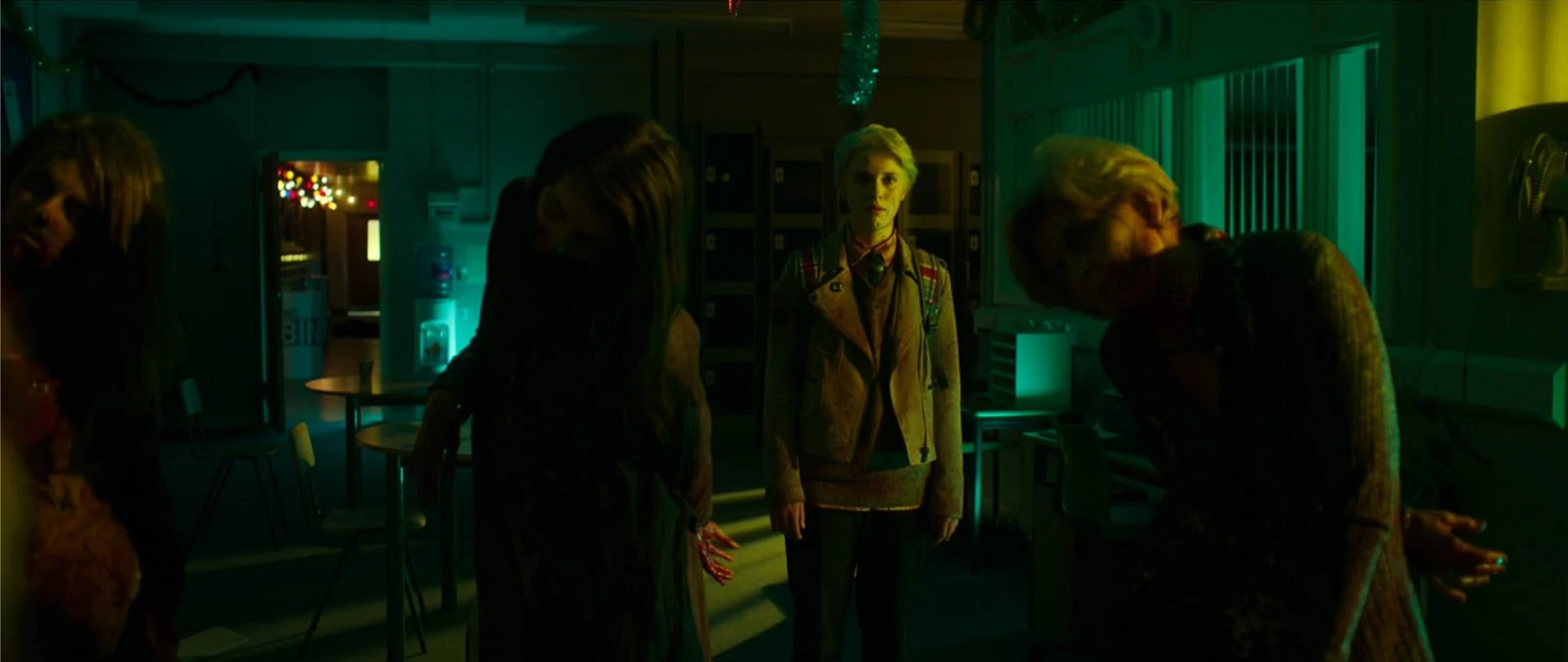

Deane shares her experiences of lensing Anna and the Apocalypse (lead image), directed by John McPhail, and making choices during the two-camera shoot which featured 14 musical numbers and plenty of characters and action. “It is an unusual film with an interesting premise and a wild genre mix. It was comedy, so we wanted wider close-ups to see interactions that let the comedy come through. We used spherical lenses and cropped into 2.39. We shot on Cooke S4s which match well between lenses and is a good idea to save time matching shots in the grade. At t2, the lenses are reasonably fast which was great for the Christmas lights.”

FROM CONCEPT TO PRODUCTION

For every project Korner works on she collaborates with the director to establish a clear sense of the framing and movement, which is born in the story and develops with the character. “The young girl in The Road Dance inherently doesn’t belong to the island, the world of potato farmers she’s born into – she dreams of a future elsewhere. So whenever possible I framed her against the sky or sea, whereas her sister and mother are firmly framed within the rich colours of the land.

“There is often a visual arc in the lighting. In The Road Dance our main character is introduced bathed in warm sunlight or the full glow of a lantern. After a tragedy befalls her, I made sure to place her in the cool areas of the frame, or just at the edge of the light.”

Deane goes through the script to storyboard but also to talk about the character arcs and the essence of each scene with the director. On the day they will have either a shot list or storyboard as a starting point. “Then when we block and if we see something better or have to make changes, I know that together we are going to make sensible decisions that will work for the story even if we have to amend our plans.

“I used a lot of Christmas LEDs and festoons in Anna and the Apocalypse as one of the visual concepts was to see a lot of Christmas in the background of every shot. The festoons also allowed me to light a long corridor without going through the doors or putting up overheads. I tested the LEDs for flicker, particularly as we had high speed scenes. I also tested filters to find a nice halation on the point sources and chose Tiffen Black Pro-Mist filters.”

For all cinematographers, shot choice, coverage composition, and movement are fundamental ways to ensure the film is cohesive, even though there is forward momentum in most of the visual concepts. “In preparation I am looking to develop a Matrix-style cord between myself and the director so I know if they will like it when I’m framing up. Trust and confidence are important so I can make decisions that work for the production based on pre-production work with the director and the other HODs,” says Barron.