Toby Elwes’ National Film and Television School (NFTS) graduate short film is a claustrophobic journey into the depths of the sea. The project involved building ambitious sets, shooting dry for wet, and capturing the drama of both cityscapes and seascapes.

Dive follows an industrial deep sea diver, Paul, on his final contract to construct an oil drill at the bottom of the North Sea.

Despite advances in deep-sea machinery, underwater construction of this kind still needs divers to spend months travelling up and down to the sea bed. To survive the massive pressure change, divers like Paul and his team must live in pressurised pods onboard their oil rigs. In preparation, they must spend a week locked in these capsules to slowly acclimatise.

With nowhere to hide from his three team members during this time, Paul’s true intentions to sabotage the oil exploration begin to emerge. The intense claustrophobia of this pressure chamber brings to the surface Paul’s trauma and motivation.

Mourning the death of his daughter, a climate activist who protested her father’s occupation, we follow Paul’s struggle to maintain his composure on his journey to the bottom of the sea.

British Cinematographer: What were your initial discussions about the visual approach for the film? What look and mood were you trying to achieve?

Toby Elwes: Written by our director Will Peppercorn, Dive was based around the very technical exercise of saturation diving. Our initial research was to examine footage of deep sea dives. Whilst watching these tiny shaking metal capsules 300ft underwater, we felt a connection with films of precarious space missions of the 1960s and ’70s.

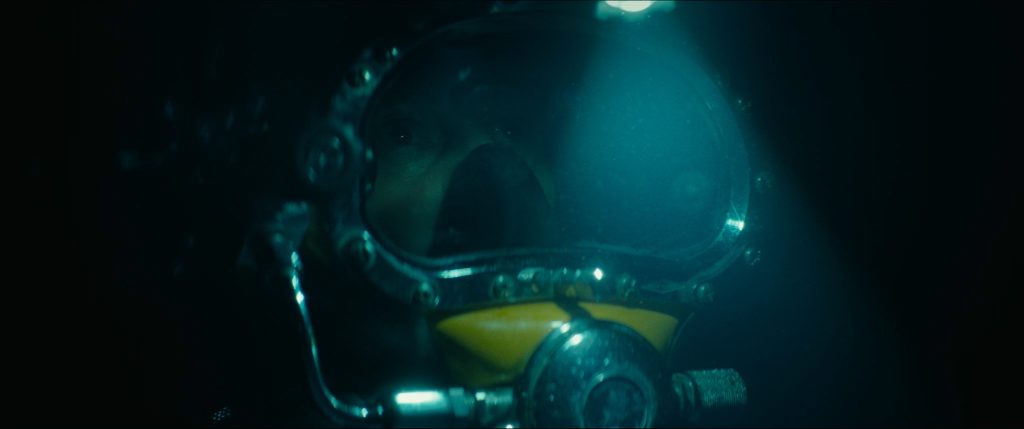

Like an astronaut’s journey, Paul’s dive takes place in three spaces: the initial week in the pressure chamber, the journey to the bottom of the sea in a rusty and creaky diving bell, and the inky void of the sea floor itself. For each space, we centred our attention on capturing the unstable and dangerous nature of the environments. I was especially keen to use flickering lights and vibrating camera work in the diving bell, so the cinematography conveyed the mechanics at work as they descend deep underwater.

BC: What were your creative references and inspirations? Which films, still photography or paintings were you influenced by?

TE: I remember pulling up the rocket scene from Linus Sandgren FSF ASC’s work on First Man, Jost Vacano ASC BVK’s oily imagery for the 1981 Das Boot and Hoyte van Hoytema ASC FSF NSC’s ship interiors for Dunkirk. In all these cases, I concentrated on how cinematography helped make the sets feel active, industrial and precarious; bending and vibrating due to the forces of water and pounding engines.

BC: What filming locations were used? Were any sets constructed? Did any of the locations present any challenges?

TE: The most exciting thing about this project were the ambitious sets designed by Darya Naumchenko, which were built on the main stage at the NFTS. These were a larger pressure chamber with bunk beds and an eating area, and a smaller diving bell with a hatch to the sea bed.

It was great developing these cylindrical sets with Darya and Will, preserving just enough space and access points for practicality, whilst making sure we could create the claustrophobia key to these pressure chambers.

I also tested out ways to visualise the descent of the diving bell underwater. Divers exit these diving bells through a hatch in the floor and to achieve this Darya built our set on a raised platform with a trap door. As well as securing a tray of inky black water under the hatch to shoot down at, I also wanted to shoot up through the portal as if the camera was a few feet underwater. Ultimately, I was able to rig a mirror at 45 degrees in a fish tank full of water under the raised platform which allowed me to get this underwater angle.

Our ultimate challenge was depicting the underwater environment on the bottom of the sea floor. It was clear that early suggestions to film underwater in diving pools would be a massive drain on the budget, our shoot time and coverage. This thankfully pushed us to think more creatively. Aware that our divers would be fully suited in deep sea gear (so wouldn’t have flowing clothes or hair on show), I felt we could test dry for wet techniques on a blacked out stage.

Through testing, I found that if we pumped a large amount of haze onto our stage, filmed at high speed and lit our void with our diver’s head torch, we were able to create a convincing sea bed environment. This approach was great as it meant we didn’t need body doubles and could use defunct diving suits no longer rated for underwater use. It also meant our designer could create a textured seabed of dirt and rusty pipes, and I could shoot many more angles without the restrictions of underwater camera housing. It was good to test this approach in prep and hone the details, ultimately collaborating with our DFX team, Oliver Lemery and Danielle Parker, who composited floating particles and rising bubbles to aid the illusion.

BC: Can you explain your choice of camera and lenses? What made them suitable for this production and the look you were trying to achieve?

TE: From the outset we wanted to convey the scale of the landscapes: the cityscape of the opening protests in central London, to the northern seascape and the deep sea void at the end of the film.

It felt appropriate to shoot this project widescreen to push these expanses, as well as offering me a frame which could hold four characters simultaneously. We paired our Alexa Mini with Cooke anamorphics, kindly supplied by Cooke themselves. This offered me an anamorphic aesthetic alongside good close focus and edge resolution, allowing me to frame multiple characters cosied up in the pressure chamber.

BC: What was your approach to lighting the film? Which was the most difficult scene to light?

TE: I paid special attention to the practical light fittings and bulkheads in the films mentioned above. As I had the luxury of building fixtures into our set, I was keen to emphasise the utilitarian nature of the lighting. It was fantastic designing open backed bulkhead fittings and industrial strip lighting into Darya’s set plans. I was then able to run diffused 650w tungsten lamps through all these fixtures and back to a lighting desk.

I knew that the sets would have to be small to stress the claustrophobia of these chambers, so making sure I could disguise my lighting as practical fixtures and preserve floor space for the actors and camera was paramount.

It was also a massive benefit to the flow of production to have full dimming control over each fixture via radio to our lighting desk. By rigging the primary lighting in this way, I was then able to concentrate on balancing the bulkheads to convey different times of day and moods in our windowless set. Much like the final scenes of our film being lit by a single head torch, I was keen to keep our lighting minimal and motivated by industrial fixtures.

BC: What were you trying to achieve in the grade?

TE: It was great having our colourist, Nate Skeels, involved from an early stage. We were able to develop a shooting LUT and discuss our different environments and ambitions, such as the moody, murky and green environment at the bottom of the sea. Engaging with Nate in preproduction and discussing the palette in conversation with our designer and director, meant that our intentions were preserved throughout shooting, the dailies and the edit.

Having a consensus on the look meant Nate and I could concentrate on the details during our grade. We were able to pay special attention to extending the oily and industrial palette of the set, as well as hone the underwater environment.

BC: What were the most challenging parts of the film to shoot and how did you overcome those obstacles?

TE: Beyond the creative challenges presented by the sets and our dry for wet technique, we had some physically challenging locations to shoot in!

On our final shoot day we drove down to Portland harbour and took our lead actor out on a big industrial tug boat to capture his journey out to the oil platform. Faced by the elements and pretty serious swell, our team had to seriously bolt down our camera positions. We all still feel nauseous rewatching those sequences, but I’m pleased we persevered with our rigging, drone angles and grip to keep achieve our shots.

Will conceived the opening of the film to take place at an environmental protest in central London and on a nearby roof. Whilst we did shoot a few cut aways with background artists, we set our sights on filming our main sequence at a real protest. We knew we would have to be nimble but I still wanted to preserve a solidity to the image as we travelled through the crowds. With limits on equipment, I opted to combine a Sony FX6 with Kowa anamorphics, generously supplied by Movietech. This meant I could operate off a small Steadicam, light enough to quickly squeeze through the crowds. This approach meant we could be fast and reactive, chasing interesting parts of the protest such as flares and drummers.

BC: What was your proudest moment from the production process? Is there a specific scene or shot that you’re especially proud of?

TE: It’s got to be developing the underwater shooting process and tweaking how we approached filming dry for wet.

BC: What lessons did you learn from this production that you’ll take with you onto future productions?

TE: Be prepared for any scenes set on the open sea!

BC: What would be your dream project as a cinematographer?

TE: Brainstorming, testing and researching how to capture ambitious scenes set out at sea, in pressure chambers, at active protests or deep underwater pushed us to think creatively. I hope to keep working on stories which demand innovative and creative cinematography!