DERRING-DO!

Ben Davis BSC / The King's Man

DERRING-DO!

Ben Davis BSC / The King's Man

BY: Ron Prince

Rewind… to the early years of the 20th century. As a collection of history's worst tyrants and criminal masterminds plot a war that could wipe out millions, one man and his protégé must race against time to stop the evil-doing villains.

Following Kingsman: The Secret Service (2014) and its follow-up Kingsman: The Golden Circle (2017) (both shot by DP George Richmond BSC), director Matthew Vaughn has taken his action-packed, spy/comedy saga back in time to explore the origins of the 'Kingsman' agency - the world's first independent secret intelligence service - in The King's Man.

Set against the backdrop of World War I, the swashbuckling movie delves into the history of the covert espionage organisation, whilst taking-in contemporary figures and events, including the influential mystic Rasputin, and the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, whilst also setting-up Easter eggs for the next episode in the franchise's future.

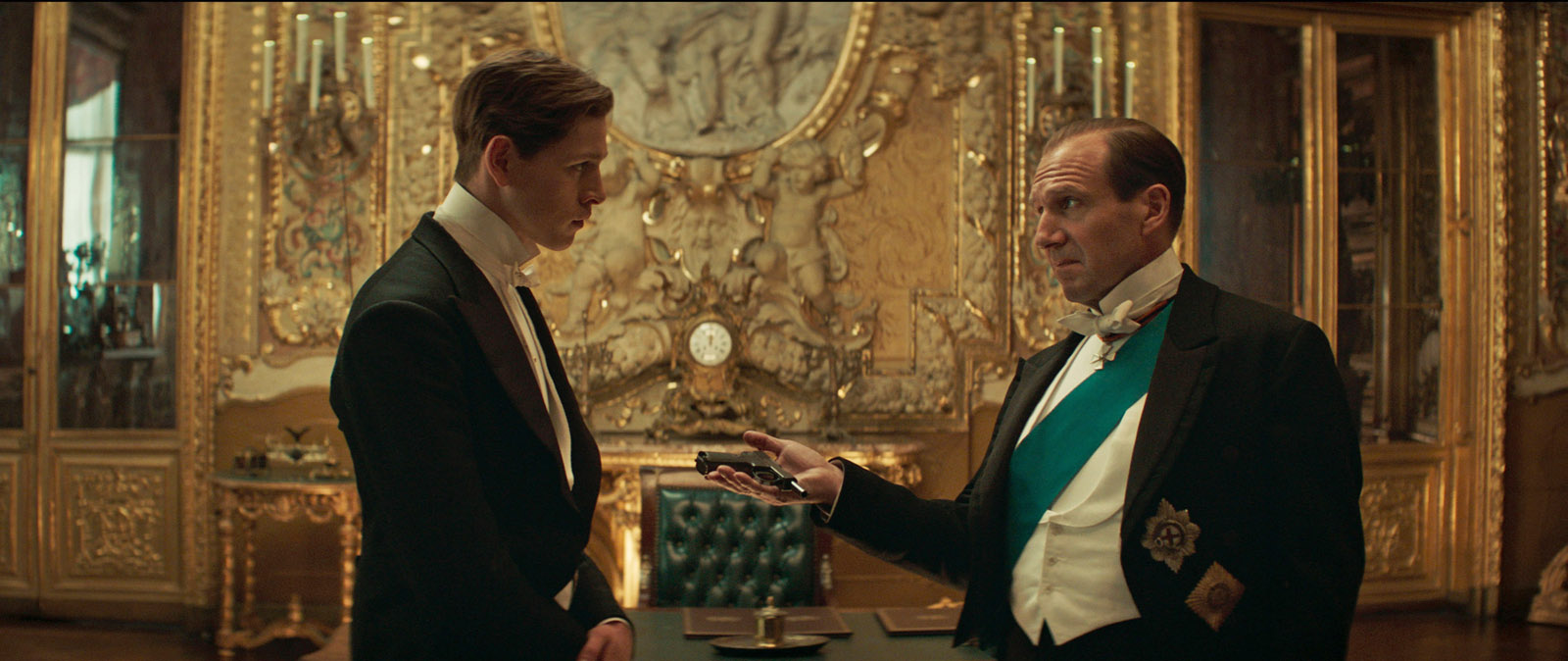

The 20th Century Studios film stars Ralph Fiennes, as the Duke Of Oxford, who takes young soldier Conrad, played by Harris Dickinson, under his wing, along with Djimon Hounsou as Oxford's butler, Gemma Arterton as the gun-toting servant-cum-spy, Polly, and Rhys Ifans as Rasputin.

Cinematographer Ben Davis BSC reunited with Vaughn for The King's Man, the pair having previously worked together on the director's films Layer Cake (2004), Stardust (2007) and Kick-Ass (2010). Davis' wider credits include Guardians Of The Galaxy (2014), Avengers: Age Of Ultron (2015), Doctor Strange (2016), Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017), Dumbo (2019) and Captain Marvel (2019). His most recent production was the Marvel superhero movie The Eternals, directed by Chloé Zhao, scheduled for release in early 2021.

Principal photography on The King's Man started in April 2019, concluding some 85 shooting days later. The production was based at Longcross Studios, where many sets were constructed on the stages and backlot, including exuberant palace interior/exteriors and the villains' mountaintop lair. Davis had a ten-week prep period, during which the stunt, fight and VFX sequences were rigorously rehearsed, and the set designs worked-out in meticulous detail, as per Vaughn's wont.

Also at Longcross, Davis ensured the production team had the benefits of watching projected dailies during the shoot. "I don't understand why in this age of digital cinematography, that there is a reluctance to watch dailies on a big screen," he says. "When you are making a film for the cinema, it's important to review the image at scale - and not on a monitor - with the director and other key heads of department, especially make-up and wardrobe, in attendance."

Physical locations included Hankley Common, Surrey, used for the movie's opening scenes in the Transvaal, with other palatial scenarios shot in historic buildings in Turin and Venaria Reale, Italy, the latter of which was transformed into Sarajevo.

British Cinematographer caught up with Davis during lockdown to discover more about the cinematographer's work on the movie.

What was your initial reaction to the script?

BD: Matthew told me that being a period prequel, set during the origins of WWI, he wanted this to be a far more classical and stately piece of cinema in the way it was shot - for it to have a look and style that went back to a structure of filmmaking that is not so commonplace now, and for it to have a far less lyrical look than the first two films.

What creative references did you consider?

BD: We had references for certain scenes - such as vast landscapes and dramatic action sequences - rather than for the film as a whole. The Man Who Would Be King (1975, dir. John Huston, DP Oswald Morris BSC), and certain scenes with big high wides from Out Of Africa (1995, dir. Sydney Pollack, DP David Watkin BSC), were among our reference points for the opening of the film set in the Transvaal, although we shot that on location in Surrey. We also looked at films with classic sword fights, including Errol Flynn movies, to see how the action was staged and covered photographically.

Essentially, we wanted to go back to periods of filmmaking that had plenty of traditional dolly and crane work. Matthew really did not want to be up close with wide-angle lenses, and no intimate handheld - all of which we see a lot of these days. Rather, he wanted the framing to sit back more, and for the audience to watch the action through longer lenses and sweeping tracking shots.

"For me, filmmaking is about the journey, the camaraderie and friendships, you have during the process. I remember these experiences as much as I do the films themselves."

- BEN DAVIS BSC

That said, we had to balance the gravitas and history of the film with the outrageous action and fighting scenes Matthew' is known for generally in his work, and which have become visual hallmarks within the Kingsman world. During pre-production I looked closely at the set designs and what the second unit would be shooting to make sure these two styles would mesh together. I was a bit nervous about how this would work, but having seen the film I think they come together rather joyfully.

Tell us about your selection of cameras and lenses?

BD: Matthew loves widescreen Anamorphic lenses - the aberrations, the way they flare and the bokeh - and this played very well to the contrivance of our classical filmmaking approach. After testing I settled on shooting with the large format ARRI Alexa65, plus Panavision Ultra Vista lenses, which are rather beautiful, handcrafted works of art in themselves.

These lenses have a 1.65x Anamorphic squeeze that covers the full frame of the Alexa65. The images they deliver are similar to the Ultra Panavision 70 1.3x squeeze look and the organic nature you associate with the C-series Anamorphics. The picture is not too sharp, there's a nice transition between details and a pleasing fall-off between foreground and background, giving you a fulsome image that delivers the appearance of depth. I am not particularly fond myself on the blue hard-line horizontal flare you get with some Anamorphics, but the Ultra Vistas did not do that - their flares are rather beautiful.

I was not interested in shooting wide-open with a very narrow depth-of-field - which is more of a modern conceit - and tried to work at a minimum of T4 to T5.6, as these stops give a good balance between the foreground and background detail, and further supported the type of filmmaking we wanted. Those T-stops also gave my focus pullers a fighting chance, as the Ultra Vistas with a large sensor are very challenging.

Our set of lenses included 35mm, 40mm, 50mm, 60mm, 75mm, 100mm, 135mm, 180mm, 290mm and 400mm focal lengths. Generally we worked with the longer-range 60mm, 75mm and 100mm lenses for action and faces, and used the wider-angled glass for the wider establishing shots. I rated the Alexa65 at 800ISO, but went up to 1200ISO if we ever needed an extra bit of stop.

That said, we had to balance the gravitas and history of the film with the outrageous action and fighting scenes Matthew' is known for generally in his work, and which have become visual hallmarks within the Kingsman world. During pre-production I looked closely at the set designs and what the second unit would be shooting to make sure these two styles would mesh together. I was a bit nervous about how this would work, but having seen the film I think they come together rather joyfully.

Tell us about your selection of cameras and lenses?

BD: Matthew loves widescreen Anamorphic lenses - the aberrations, the way they flare and the bokeh - and this played very well to the contrivance of our classical filmmaking approach. After testing I settled on shooting with the large format ARRI Alexa65, plus Panavision Ultra Vista lenses, which are rather beautiful, handcrafted works of art in themselves.

These lenses have a 1.65x Anamorphic squeeze that covers the full frame of the Alexa65. The images they deliver are similar to the Ultra Panavision 70 1.3x squeeze look and the organic nature you associate with the C-series Anamorphics. The picture is not too sharp, there's a nice transition between details and a pleasing fall-off between foreground and background, giving you a fulsome image that delivers the appearance of depth. I am not particularly fond myself on the blue hard-line horizontal flare you get with some Anamorphics, but the Ultra Vistas did not do that - their flares are rather beautiful.

I was not interested in shooting wide-open with a very narrow depth-of-field - which is more of a modern conceit - and tried to work at a minimum of T4 to T5.6, as these stops give a good balance between the foreground and background detail, and further supported the type of filmmaking we wanted. Those T-stops also gave my focus pullers a fighting chance, as the Ultra Vistas with a large sensor are very challenging.

Our set of lenses included 35mm, 40mm, 50mm, 60mm, 75mm, 100mm, 135mm, 180mm, 290mm and 400mm focal lengths. Generally we worked with the longer-range 60mm, 75mm and 100mm lenses for action and faces, and used the wider-angled glass for the wider establishing shots. I rated the Alexa65 at 800ISO, but went up to 1200ISO if we ever needed an extra bit of stop.

Whilst the Alexa65 is an amazing camera, one drawback is its size - it is a big beast. So whilst it worked fine on the dolly and crane, for sword-fighting sequences, when the camera was in amongst the performers or even attached to them, I needed smaller, lighter cameras. On those occasions we used Alexa Minis, or the Blackmagic Pocket and Micro cinema cameras. The Blackmagic devices are small, easy-to-operate and very economical. The footage they record also matches well with the Alexas in terms of dynamic range and colour science.

Did you create any LUTs for the film?

BD: I used one very basic film-emulation LUT - that I originally developed with colourist Adam Glasman at Goldcrest - for the entire movie. I have changed my approach to digital workflow over the last few years, and don't spend nearly so much time in the DIT tent during production. Having multiple LUTs, grading and adjusting the look as you shoot is a distraction I don't want.

Also, you have to be careful as a cinematographer not to get removed from the process. You are the head of the camera department, and must lead from the front, and not be tucked away in a tent off-set constantly tweaking colours.

It is important to be at the centre of where the filmmaking is taking place. It is a privilege to be on-set with the actors and director and your crew. So these days I stay on-set, with a small, correctly calibrated monitor, use one LUT, and light and shoot they way I want the picture to look rather than using LUTs or CDLs to manipulate the image.

Also, on films like this, when you have a lot of VFX shots and multiple VFX vendors, it pays to have a streamlined workflow, without multiple looks, LUTs and CDLs flying between the post production departments. It is far better to keep your pipeline simple, and to ensure that everyone sees the images as you intend them. You should even go into the edit room and ensure the monitors are set up correctly. I do exactly this on every production, including The King's Man

Who were your crew?

BD: My A-camera operator was Julian Morson, with Sam Renton on B-camera. Their respective focus pullers were David Cozens and Leigh Gold. They had their work cut out with those Ultra Vista lenses, but did a great job. My DIT was Tom Gough, one of the nicest people you could ever wish to meet, and who has the most charming and polite manner on-set. My gaffer was David Smith, a very clever gaffer who is up with all of the very latest innovations in LED lighting and control systems, with whom I have enjoyed working for many years. I was very fortunate to have a great grip, Kevin Fraser, who demonstrates a love for his job every working day. The second unit was led by Fraser Taggart - he's excellent and I was very lucky to have him on the team.

Tell us about the camera movement?

BD: Matthew likes to move the camera, and on this film he wanted to move it in very classical ways. During pre-production we made sure the floors of the sets were flat and smooth for the dolly tracks and any dance-floor dolly moves. We also did a lot of cranework, and in this respect I was very impressed by the Chapman Leonard 75ft Hydrascope. It has a big range and can travel a long way, yet it comes with a small footprint compared to its size, not much bigger than the 50ft version. There was very little Steadicam and precious little handheld in this production on first unit, as Matthew did not want those approaches for this film. The second unit used a Ronin 2 gimbal, in combination with the Alexa Mini, to cover their various stunt and action work.

How about your approach to the lighting?

BD: When you look at the changing technologies used in filmmaking, lighting has come on leaps and bounds in terms of the LED RGBW fixtures we now use and the ways these can be combined and colour-controlled from a dimmer board. The way you can switch from day to night, or adjust the colour temperature from cool to warm, all in a matter of seconds is really quite amazing. I also really the environmental impact - the way we power our sets these days is much greener and more economical that it was just a few years ago.

I don't always reference particular work in regard of how it might inform my lighting but try to keep myself open to all forms of the visual arts. Every film has its own language that speaks for itself, and you can arrive at a creative decision with influences from multiple sources or experiences.

We used all manner of RGBW Sky Panels, Space Forces and Astera tubes to light our various warm, candle-lit interiors and wintery exterior scenes, but I actually found our smallest and simplest set, the Kingsman tailor's shop in Saville Row, the hardest one to light.

Essentially, it was a square box room with a desk, plus even smaller changing rooms with mirrors. This arrangement sort of dictated that I had to top-light, but I am not a great fan of top-lighting, as it can be rather ugly on faces, with highlighted noses and shadows under the eyes. To make these scenes work, the lighting became all about hidden lamps and bounced light all the while trying to keep the shooting floor clear and allow something close to a 360-degree field-of-view. Also, I found the green paint on the walls of the tailor's shop too modern, and not a 'period' enough in colour. So I fought that by lighting the walls separately from a warmer light source, to give an overall warmer tone.

How about your approach to the lighting?

BD: When you look at the changing technologies used in filmmaking, lighting has come on leaps and bounds in terms of the LED RGBW fixtures we now use and the ways these can be combined and colour-controlled from a dimmer board. The way you can switch from day to night, or adjust the colour temperature from cool to warm, all in a matter of seconds is really quite amazing. I also really the environmental impact - the way we power our sets these days is much greener and more economical that it was just a few years ago.

I don't always reference particular work in regard of how it might inform my lighting but try to keep myself open to all forms of the visual arts. Every film has its own language that speaks for itself, and you can arrive at a creative decision with influences from multiple sources or experiences.

We used all manner of RGBW Sky Panels, Space Forces and Astera tubes to light our various warm, candle-lit interiors and wintery exterior scenes, but I actually found our smallest and simplest set, the Kingsman tailor's shop in Saville Row, the hardest one to light.

Essentially, it was a square box room with a desk, plus even smaller changing rooms with mirrors. This arrangement sort of dictated that I had to top-light, but I am not a great fan of top-lighting, as it can be rather ugly on faces, with highlighted noses and shadows under the eyes. To make these scenes work, the lighting became all about hidden lamps and bounced light all the while trying to keep the shooting floor clear and allow something close to a 360-degree field-of-view. Also, I found the green paint on the walls of the tailor's shop too modern, and not a 'period' enough in colour. So I fought that by lighting the walls separately from a warmer light source, to give an overall warmer tone.

How did you deal with the VFX?

BD: I worked very closely with the excellent Angus Bickerton, our VFX supervisor. The great advantages of modern film lighting technology really came to bear on some of our VFX shots.

For example, there's a scene when the Duke Of Oxford flies over the mountains at dawn in a period bi-plane. We started by shooting backplates near the Swiss/Italian border at sunrise, before later shooting Ralph and the aeroplane on-stage at Longcross. Rather than shooting the sequence against blue or greenscreen, we shot against the white background of large cyclorama. I was able to analyse the backplate shots, and could then quickly light the cyclorama with LEDs to match, with the same blue in the sky and the same warm band of early morning sunlight at bottom.

Shooting this way you avoid the struggle of correcting or mitigating blue or green spill, as all of the reflections and flesh tones look correct. It's a great way to work. I can easily see how the new live LED-projected virtual environment technologies, such as The Volume that was used on The Mandalorian (2019, DP Greig Fraser ACS ASC), will be a fabulous proposition in the future for all manner of shots and VFX work.

What were your working hours?

BD: They were long, and I typically worked six or seven-day weeks, but I don't mind that. During production I was usually up at 5.30am and on-set with David, my gaffer, before everyone else appeared, getting ready for the day ahead and pre-lighting up-and-coming sets. By the time the shooting day wrapped, and after meetings, phone calls and projected dailies, I would typically get home - to my family and my own bed, which was nice - at around 10pm.

Where did you do the DI?

BD: I completed the final grade with Adam Glasman at Goldcrest in London during lockdown. For safety, I sat in a separate theatre, and we worked on the grade for around three weeks in total over a period of time. Of course, I could have done it from home on a monitor, but as with projected dailies, when you do the DI for a cinema release you really need to view the pictures projected on as big a screen as possible. My fear was there would be a temptation to cook the look, to make the film more colourful and contrasty like the other movies in the franchise. But thankfully that did not happen. Matthew ensured the soft colour palette and filmic, period look remained intact.

Any final thoughts?

BD: For me, filmmaking is about the journey, the camaraderie and friendships, you have during the process. I remember these experiences as much as I do the films themselves. On this production, Matthew was in great form, as were the cast, and I was fortunate to have a terrific, dedicated crew. This all amounted to making the experience of making The King's Man one of the best I have ever had