A LIFETIME BEHIND THE LENS

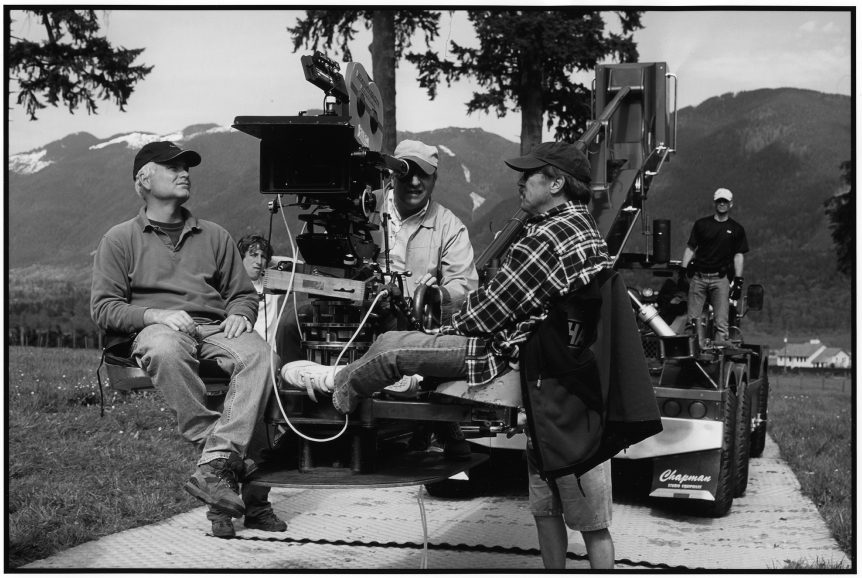

Stephen H. Burum ASC – whose body of work includes 1987’s The Untouchables, one of eight films he made with Brian De Palma, and 1992’s Hoffa – is the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award at EnergaCAMERIMAGE film festival.

If cinematography attracts people particularly attuned to blending engineering with the creative arts, then Stephen H. Burum ASC’s destiny was decided as a child.

Growing up in Dinuba, a rural town in the San Joaquin Valley, he remembers seeing a magazine called Popular Science and Mechanics with an article on the special effects used to make the 1953 feature version of War of the Worlds.

“I was a model airplane hobbyist and I just found the FX really interesting. I wanted to try it out.”

Dinuba may have been a small town but it had three cinemas including a Spanish language theatre, a converted musical hall and a Californian state-run theatre which had the distinction of being one of the few buildings with air con.

“Mainly to escape the summer heat I would go to that cinema on matinees. They used to have a very elaborate programme on Saturdays of a newsreel and cartoon, a serial and two features. One was usually a musical, the other a western or war picture.

“I saw just about everything you can think of and it kind of seeped into me by osmosis. When I went to film school a lot of students hadn’t see the movies I had. I instinctively understood the structure and storyline and could pick up all the dramatic cues. That was my best training, though I didn’t know it at the time.”

His parents either wanted him to get into the newspaper business (his mother’s family owned a local newspaper) or get a career in engineering or law. To appease them he planned to work for a film studio and attended the UCLA School of Theatre, Film and Television. “The plan was to start as an assistant for 10 years, then operate for another 10, then DP and head of the camera department. That type of corporate career path was very typical in the ‘60s.”

Instead, after college he leapt straight to DP aged just 23, shooting wildlife films like NBC TV series Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Colour for Disney Studios. He even met the legend on a few occasions.

“He asked people to call him Walt and was very matter of fact and a good leader. After I worked for about two months, I got a raise from $25 to $175 a week because Walt said he thought I was good.”

THE WAR YEARS

Burum’s upward trajectory was paused when he was drafted into the US Army as part of the Vietnam war effort from 1965 through 1967. After basic training he was assigned to produce training films at the Army Pictorial Centre in New York, where the majority of the 1200 staff were civilian.

“At least I escaped being a combat photographer,” he says.

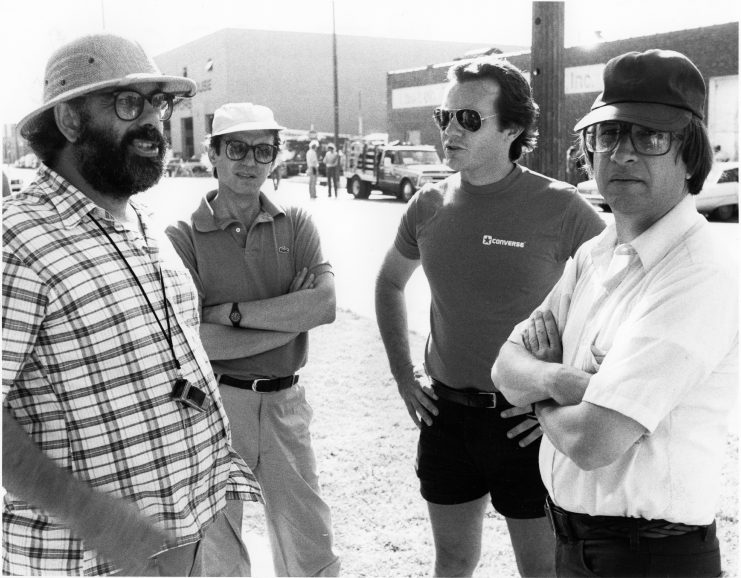

With some irony then he found himself a decade later recreating Vietnam as second unit photographer and director on Francis Ford Coppola’s epic Apocalypse Now.

“I was working in LA lighting video-taped TV programmes when I got a call from Francis. A typhoon had wrecked the location of a helicopter assault scene and he needed more coverage for the attack and the boat going upriver. I was trying to get into the union and said I wasn’t interested in being a second unit director.”

Burum suggested Carroll Ballard, a mutual colleague from UCLA. “Francis said, ‘Carroll said you should do it.’ They twisted my arm.”

Burum spent nine months in the Philippines, initially with Coppola and Vittorio Storaro ASC AIC, then filming under his own command.

“We were all trained by the same people so I already knew what Francis would require to piece it together. That was lucky because we’d only got dailies once a month. At UCLA I was taught that if I was interested in being a studio cameraman than I’d have to match every other camera person on the lot. Sometimes people get sick and they wouldn’t shut down so they’d have someone else just roll in. A head of camera department had to learn to shoot like everyone else. It wasn’t hard for me to figure out what they wanted.”

Burum’s army film training came in useful coordinating the local air force that Coppola was relying on to supply and fly helicopters.

“The Philippines air force only had sixty helicopters and while Francis needed big formation shots, the army was fighting a war against separatists in another part of the country. Sometimes we’d get four helis, sometimes 10 or 20, so scheduling was very difficult. The other problem was that the pilots couldn’t fly the big, tight formations we needed. In the end we flew in some US pilots and had them interspersed among the formation.

“I knew what heli formations were and how to line them up,” Burum adds. “We’d get everyone up in the air and fly one, then we’d get everybody to assemble and turn 90-degrees. Then we’d fly the rehearsal leg to get everyone in position, then another assembly leg. The final leg, we recorded.”

On return, he shot second unit for Ballard and Caleb Deschanel ASC on The Black Stallion (1979). When Deschanel directed The Escape Artist (1980) he asked Burum to shoot it for him, marking his first main feature DP credit.

Now he was up and running. Sidney J. Furie hired him to shoot horror picture The Entity (1982), a director whom Burum reveres as one of the very best he is worked with.

BRAT PACK ERA

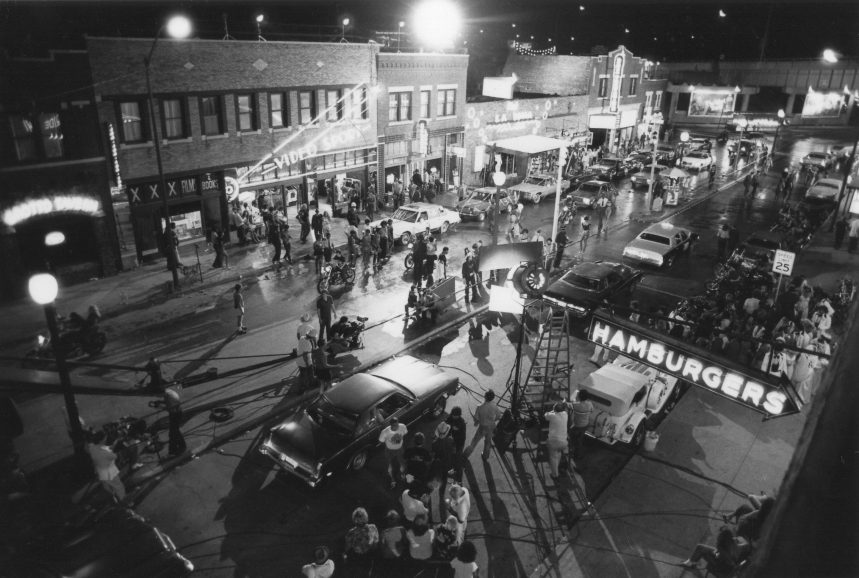

Then came a pair of Susan Hinton novel adaptations, lean youth dramas sparkling with indie spirit which launched the Brat Pack career of actors Tom Cruise, Emilio Estevez, Matt Dillon, Rob Lowe and Ralph Macchio.

“The Outsiders was suggested to Francis by a junior high school class in Fresno. One of the students was a cousin of mine but I didn’t tell him that. Since he considered me a very efficient cinematographer, Francis wanted me to shoot the picture, which we did in 40 days. He had this rule not to shoot more than three takes. He’d make long elaborate rehearsals so that all the kids were already up to snuff when we shot. We’d sometimes only need two takes and we never printed more than one.”

As a reward, Coppola offered Burum the chance to shoot 1983’s Rumble Fish. “He asked me what I wanted to do with the film and I said to shoot black and white because it was maybe my only chance. I had shot 50 black and white films at film school and loved it. He agreed and said it was his gift to me for doing a good job.”

Monochrome is a common aesthetic choice in recent years but a rarity in theatrical releases of the time. A review from 1984 in the ASC journal was impressed: ‘Compared to even the luminous, lithographic grey scale photographed by Sven Nykvist [ASC FSF] for Ingmar Bergman, Burum’s Rumble Fish is seared on the screen like burnt charcoal and fuming dry ice.’

His agent got him an interview with Brian De Palma who was casting for cinematographers to shoot his next project. Burum had to shoot some test material and won.

“When we first met, Brian said, ‘let me tell you what I don’t like about DPs. I don’t like those who mess around and take a lot of time.’ I said, ‘let me tell you what I don’t like about directors. Those who don’t direct. Doing both jobs is above my pay grade.’ He hired me and we had this understanding from the beginning. I’ve had to back up some people who are pretty horrible and lazy but Brian was fabulous.”

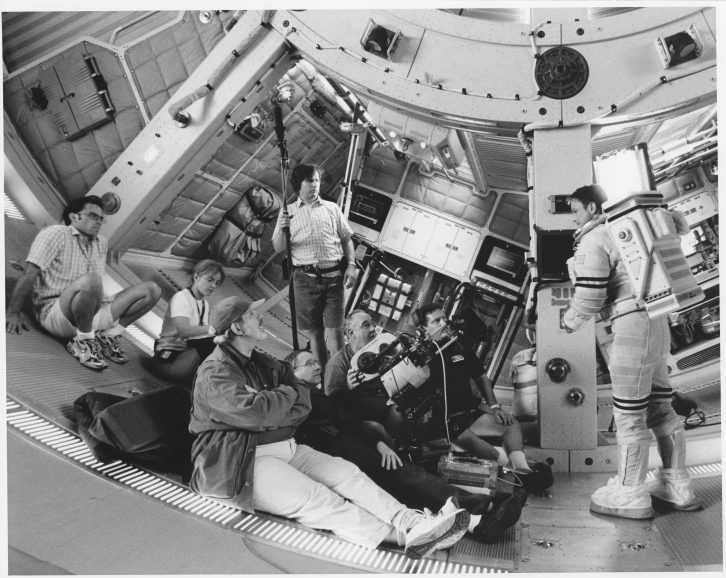

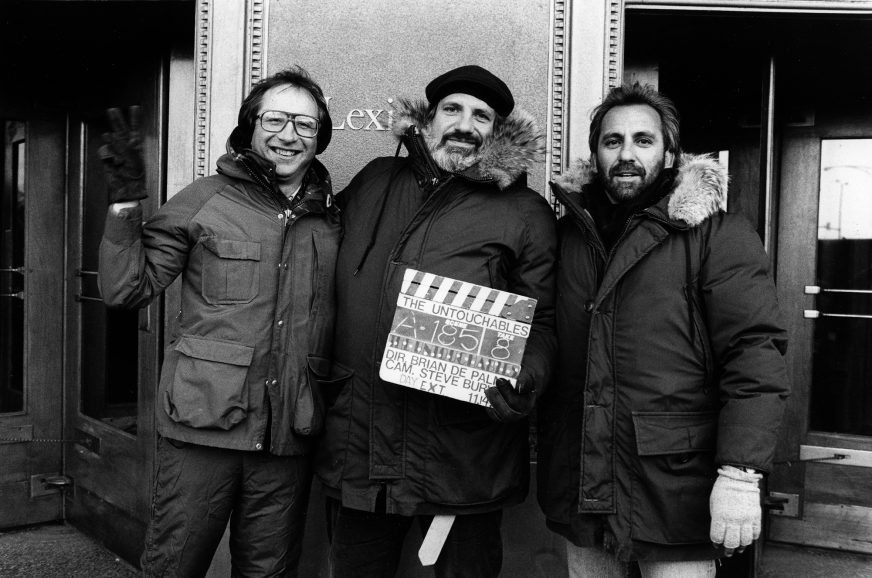

After Body Double the pair embarked on a further seven pictures including The Untouchables, Casualties of War, Snake Eyes, Mission: Impossible, Carlito’s Way, Raising Cain, and Mission to Mars.

The climactic sequence in The Untouchables with a pram falling in slow motion down the steps of Chicago’s Union station appears to be in homage to Sergei Eisenstein’s Odessa steps montage from Battleship Potemkin.

“It’s funny but that scene was not in the original script,” Burum reveals. “David Mamet’s script had the bookkeeper escape on a train and Elliot Ness’ team drive all night to catch it and block the railroad before a gun fight on the train, but Paramount didn’t want to spend the money. Brian’s next idea was to have Ness’ wife give birth and when he comes out of the hospital is when we have a gun fight. But we couldn’t find a suitable exterior location so the Chicago train station was used by default. It was difficult to get permission, so we had to shoot at night bringing in extra lights to shoot high speed. Those critics who see a pram and think Potemkin should know the original was a much better sequence.”

UNTOUCHABLE TALENT

His favourite shot in The Untouchables is a technocrane sweep of a dressed Chicago street for which the production had to fight tooth and nail for the City to agree to remove large cables and telephone poles. “The first time I saw it with the soundtrack I fist pumped ‘Yes!’ because to me it was this big Hollywood movie shot.”

He also worked with directors including Hal Ashy (8 Million Ways to Die); Bob Rafelson (Man Trouble); Joel Schumacher (St Elmo’s Fire); Ivan Reitman (Fathers’ Day) and Martin Bregman (The Shadow).

“You learn on each job. For example, there are fast actors and slow actors. Some get it on take one. Others need a dozen before they find their rhythm. Once you’ve shot the master, you have to figure out who to go to first. You want the fast actor because usually they burn out after four-five takes and you want them while they’re still hot. Plus, it gives the slow actor extra time to get up to speed. No-one ever tells you that in film school.”

Al Pacino, who starred in Carlito’s Way, is a ‘fast actor’; “Al has so much energy in what he does it exhausts him. You just have to get him first.”

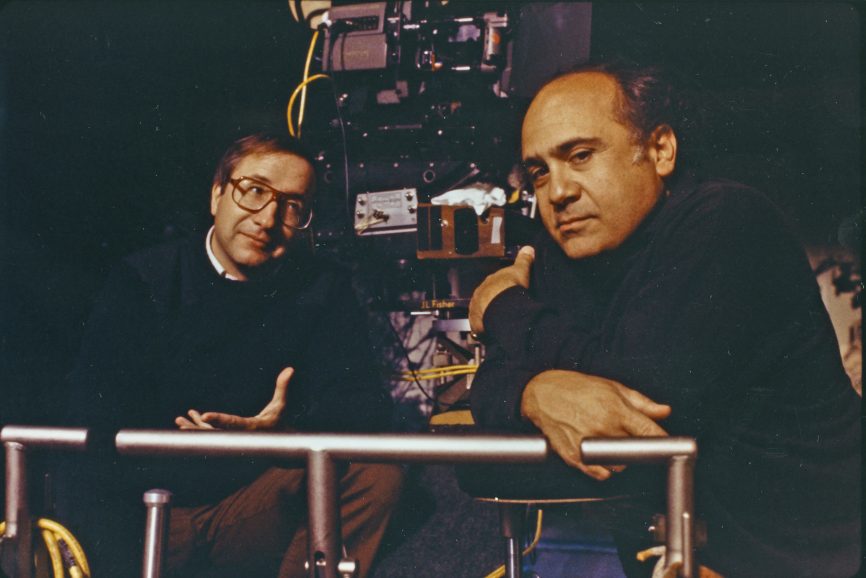

So too is Jack Nicholson, who played Jimmy Hoffa in Danny DeVito’s 1992 biopic of the union boss, Hoffa. “Jack understands movie staging so well. If you’re having trouble with an actor not hitting their mark, he can do his scene and if that person drifts he’ll be this big sheepdog and herd them in the right direction. He is totally aware of his camera and lens, the background and where the other actors are. He saved many shots on Hoffa.”

The film was praised for its cinematography, landing Burum his only Oscar nomination, but it disappointed at the box office.

“The problem was that Danny didn’t get enough time to edit it. The weakness of the picture is you don’t understand Hoffa’s motivation for what he does. That’s what Scorsese’s version (The Irishman) gets right but it was the element missing in Hoffa.

“We did a lot of dissolves for transitions rather than just cutting to the next scene. Danny wanted scenes and individual shots to evoke memories of things that happened before in the minds of the characters. One I’m proud of happens during Hoffa’s trial and we used dissolves to speed the scene up. We are telling the story symbolically rather than didactically. To me, it’s pure cinema.”