A playful touch

Weston Razooli’s Riddle of Fire, which premiered at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival this year, was shot by DP Jake Mitchell using 16mm Kodak film to evoke the nostalgic feel of the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s children’s adventure classics.

In the digital era, director Weston Razooli stands out for his unwavering dedication to shooting on film. Proficiently demonstrated in many shorts and music videos, he again showed the courage of his convictions when making his debut feature, Riddle of Fire.

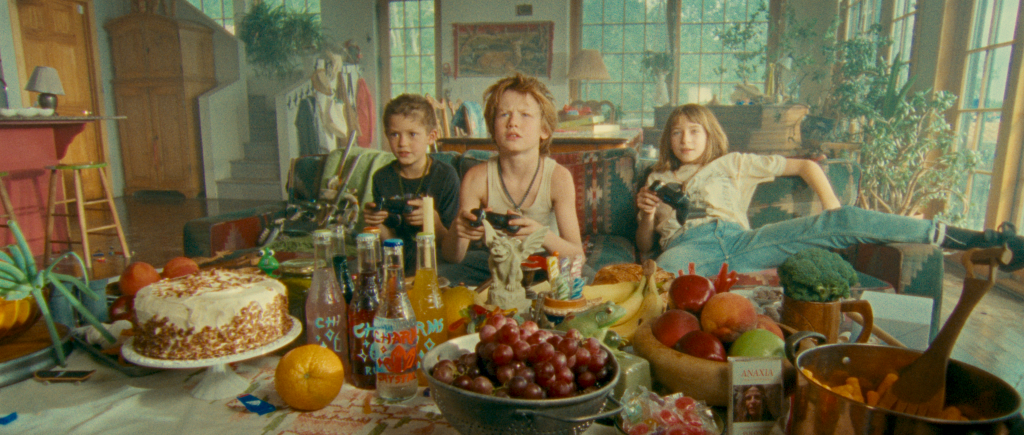

The movie is a modern fairytale set in Wyoming, echoing the adventurous spirit of classic children’s films. Three playful kids embark on a quest for their mother’s cherished blueberry pie, but a seemingly simple errand turns into an epic odyssey. Captured by poachers, they battle a witch and a clever huntsman. Amidst trials, they befriend a gentle fairy, emerging triumphant and forever valuing their magical friendship.

Razooli aimed for a feel reminiscent ‘of the forgotten live-action Disney films from the ‘60s and ‘70s – dark yet vivid contrasts’. “We utilised the ARRI 416 Super 16mm camera, predominantly relying on KODAK 50D 7203 – 16mm Movie Film and KODAK VISION3 200T 7213 16mm for both exteriors and interiors,” says the director, who also wrote and stars in the film. “Specifically, we favoured the 200T stock for indoor scenes and leaned towards the 50D variant for capturing vibrant exteriors.”

He firmly believes that this medium enables him to confidently bring his vision of the film to life, particularly in that of a stylised, fairytale world.

“I think that shooting on film really completes everything,” he continues. “It holds everything together. In terms of the creative decisions, the acting, the production, and design – it just sells the whole experience. Shooting digitally is great, but I tend to see all the cracks easier in the creative decisions of acting, the costumes, approach and design. It just doesn’t feel legitimate to me.”

Razooli’s love of film is shared by his DP, Jake Mitchell. “It can be scary, but I prefer it purely because of the look that it gives,” he says. “There are still some levels of technicality that can’t be achieved with digital, and I think that will be the case even after the technology advances further. It’s also the philosophical aspect I love, where the light that fell on that strip of film could never be replicated again. You have a sort of analogue representation of that moment that you’ve captured, where the literal photons bounce off your subjects.”

Mitchell started off with the ARRI Ultra Prime lenses “for their sharpness” but eventually switched to the Canon 6.6-66 zooms – “softer than the Ultra Prime, but on the sharper end of zoom lenses available for 16mm” – given the tight 20-day shooting schedule and the challenges of working with children for limited hours each day.

“Speed was crucial, so we minimally used the Ultra Primes – just on the first day and a couple of shots later in the shoot,” he continues. “Throughout most of the production, we relied heavily on the zooms because if we were set up for a shot but didn’t feel like the right framing, we could just easily punch out or easily punch in.”

Mitchell says that approach complemented how the film plays out scene by scene, making it feel almost like a play. “We’d have a wide shot, capture the master and all the actions – then sometimes just for simplicity’s sake, we would just punch all the way in and grab a character’s dialogue, which I think is maybe an older way of shooting at a cost. Oddly enough, it contributed to the sort of play-like style, which was unintentional but worked.”

Riddle of Fire uses a CinemaScope ratio of 2.35:1 instead of 2.39, because it offered a little extra height. “It meant we had the widescreen feeling without cropping in too much for some of our images,” he adds. “Weston and I chose it because it emphasises the storytelling – it accentuates the horizon in that it gets more room to play. We found that it adds to the general epic nature of the movie.”

The 20-day shoot primarily took place in Razooli’s hometown of Park City, Utah, where every scene was captured, with the exception of a half-day shoot at the Utah Film Studios. Notably, scenes like the nighttime car interior and the one where the kids interact with a police vehicle were filmed within the studio setting.

“We had to be sensitive to the number of hours we could shoot with the kids – and then we had all of our characters coming together,” Mitchell notes. “They all say a few lines and there’s stunts, guns, running, chasing and bottle throwing, so many elements to it. The key thing was communication, and we did that well.”

Creatively, Razooli mentions that the trickiest scenes to film usually revolved around the number of actors in a scene and determining the appropriate duration and level of blocking required.

“The climax features a long interrogation sequence with many moving pieces,” he explains. “I also have a small role in the movie, which posed its own set of challenges. However, being a very low-budget film with only one camera, we had to capture as many things as possible from various angles.”

On his approach to lighting, Mitchell comments: “I definitely had a lot of freedom on this one. We also had a lot more leeway given the fantastical nature of the film. We primarily used LED and HMIs, with the exception being tungsten or incandescent lighting, which we used in the finale of the scene in the ‘hall of fortunes.'”

Riddle of Fire will have screened in Spain, Belgium, Norway, and Poland before the end of the year, ahead of its theatrical release in 2024.