As the battle for a fairer industry continues, cinematographer (and new dad) Ricardo Diaz shares his views on the ongoing labour action with our stateside columnist Mark London Williams. With another Emmy nomination under his belt for The Marvelous Mrs Maisel, M. David Mullen ASC reflects on his lensing of the show’s finale, while it’s double trouble for fellow nominee Jody Lee Lipes ASC on Dead Ringers.

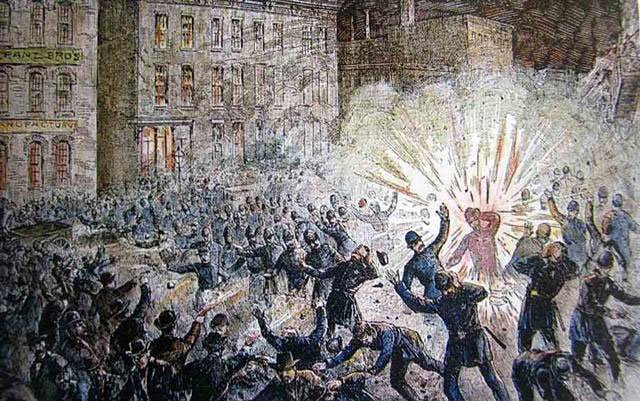

Here on the Yank side of the pond, this is being written as we head to the colloquial end of summer. On an overheated planet – in many senses of the word, now – that doesn’t come with cooler weather, the autumn equinox, or even the beginning of the school year (which keeps perniciously creeping deeper into August). Rather, it’s marked by Labour Day, an American holiday offered up as an alternative to the more potentially incendiary May Day, around which, when unions were just getting their start on these shores, some spectacular – and often fatal – clashes between workers and police took place, such as Chicago’s Haymarket Riot.

Ironically, many of the fights then were for better conditions, and more humane hours – eight, instead of the usual 12 or 16, though the latter, of course, remain somewhat standard on film and TV sets.

That is, when there are film and TV shows actually in production. Which, increasingly, there are not, as the strike(s) linger on – despite a brief flurry of the AMPTP and WGA appearing to talk with each other, although eventual leaks to the press from the AMPTP, and a response from the writers, makes it appear it was more talking at each other.

Rumours abound as folks prepare for what may be somewhat desultory Labour Day picnics this year, chief among these that a settlement may still be possible by October-ish. And, who knows, it may be, commencing a land rush back into writers’ rooms, and on to sets – on the assumption a settlement with actors follows suit – over the holidays.

In the meantime, though, there are picket lines, and more and more unanticipated time on people’s hands, along with a spreading, palpable sense that if this goes on too much longer, some of the disruptions in lives, and the entertainment business itself, may become irrevocable. Permanent, rather than temporary changes.

And not the sort of sweet and welcome changes, like, say, the arrival of a baby. That’s the kind that cinematographer Ricardo Diaz, who shot last year’s revisiting of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and now returns to the Halloween season with haunted-game-gone-wrong entry, All Fun and Games, starring Stranger Things’ Natalia Dyer.

Taking a stand

Indeed, Diaz continues with timely offerings, having lensed the third episode of this season’s Winning Time, chronicling the rise of the Magic Johnson-and-Kareem-Abdul-Jabbar-era Lakers, and the “showtime” rise of the NBA in general.

But when we talked with Diaz, he was happily distracted with a new arrival in his own household, and quite “enjoying being a new dad”. But while he was enjoying this sweetest of uses for his unintended furlough, he also notes that his wife, who recently directed, and acted in, her first feature, and is both a WGA and SAG-AFTRA member, is now, “very much on strike”.

He “admires the position the writers have taken, over the last five six years. They understand the value they create. They have an understanding of how that value has been chipped away over the last 20 years…as conglomerates try to apply pressure to the very people,” who, he says, create that value in the first place.

Diaz continues that “now both SAG and IATSE members have to deal with the reality that these prolonged strikes hit us even harder [because of the position we’re in] – because of deals we have been convinced are in our interests,” but, he thinks, really weren’t, such as raises that haven’t kept up with inflation, or healthcare benefits prone to vanish if work stoppages go on too long. “Other than the biggest of the biggest stars,” he says, “other actors who work regularly,” and certainly by extension, nearly all crew folk, are “also middle-class labourers”, with little ability to withstand long work stoppages.

That’s why he thinks that IATSE should’ve struck earlier, ahead of actors and writers. “We’ll likely never have the kind of leverage that we had in 2021 – so we missed that opportunity,” citing both Hollywood’s need to quickly start amassing new material, coming out of the pandemic, along with the supports then in place – still-suspended mortgage payments, eviction protections, COVID relief funds, etc. – that would allow a labour force more leeway in a shutdown. And more specific to Hollywood, “the studios were on their hind legs – and they were spending at the time,” as opposed to the perpetual rounds of layoffs and downsizing now.

With the IATSE contract coming up again next year, he says, “unless this next one is substantially better, we’ve lost out.” One critical thing he sees is the need for a substantial gain in turnaround time, and “that we have a life. I see no difference in the hours of work” among his colleagues now since the last contract, at least not “in the projects I’ve worked on”. And it’s important, he says, that one can also be “a father, be a mother, be a partner – and not a zombie, not a shell of who we are”.

My point,” Diaz says, “is that our battle still remains – and it was not solved to the satisfaction of most members of IATSE.”

Meaning that 2024 will almost certainly be its own “interesting” year, not just for any additional climate episodes the world experiences, or a polity-dissolving election season in the U.S., but because Hollywood’s own particular “labour days” may continue with issues for below-the-liners reaching their own critical mass when their contract expiration arrives.

Rewarding ritual

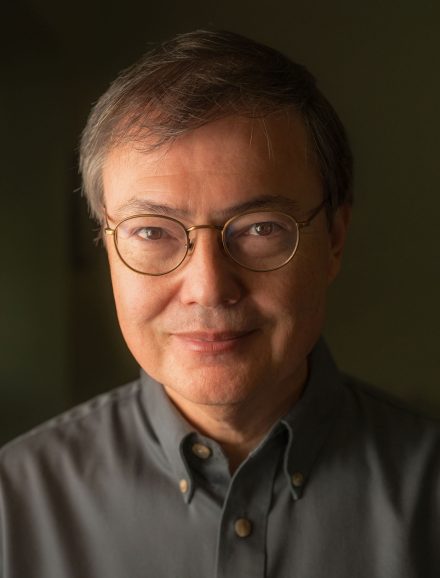

Of course, 2024 will also give us 2023’s Emmy award ceremonies, which have been strike-delayed from September to January, thus at least providing, as noted last time, a more leisurely pace to talk with some of the nominees.

One of those is M. David Mullen ASC, and it was, as we told him, a somewhat wistful occasion. Not so much because of strike related issues, but because over the course of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, it had become essentially an annual ritual to talk with him about whichever episode he’d been nominated for (often winning in the one-hour category for Outstanding Cinematography for a Series).

But now Maisel had come to its end, and indeed, Mullen was nominated for his work in the series’ finale, “Four Minutes”, which continues the season’s flash forward sequences, and also shows how Rachel Brosnahan’s Maisel finally construed her big break, on the Tonight Show-eque Gordon Ford Show, to irrevocably propel herself to the comedy fame that takes her, and the show, into the 21st century.

And on the theme of propulsion, aside from the time jumps requiring different textures of source light in each era, the series’ culminating episode is also marked by a couple of remarkable tracking sequences. One occurs in the Gordon Ford Show offices, as Alex Borstein’s indefatigable manager character, Susie Myerson, is trying to pin down producers on her client’s behalf.

The idea for the “oner”, as Mullen likes to call them, came from series creator, and finale director, Amy Sherman-Palladino, who said: “I want to go from the first floor to the second floor and back down to the first floor. Knowing the speed Amy likes to move at,” Mullen added, made simply walking backwards unsafe.

So, a Technocrane was used “from the first floor to the second”, and which point “we had to reconnect” to a Mōvi Pro to continue the shot. “Jim McConkey (SOC) operated everything,” though Jeff Muhlstock (SOC) “took over the second half of the shot”, after the “very tricky” reconnect to the Mōvi Pro.

After a couple nights of rehearsal, the shot was “80% there”, and on the culminating take, ending as the studio orchestra is ready to go “live”, there was still “some bumpiness”, later stabilised in post. Anticipating that, Mullen says “the sequence was shot with some overscan to have some room in post to smooth it out.”

As entrancing as the long Wellesian take is, it’s joined by another sequence, as Maisel’s parents, played by the estimable Tony Shalhoub and Marin Hinkle, are frantically trying to find a taxi ride to that same studio, only to run from one parked or idling cab to another, to find them all off duty, and ultimately winding up on a bus.

“We normally would’ve done that on a Steadicam,” Mullen says, especially since “Amy wanted the camera to pass through some cab windows.” McConkey would hand the camera to a strategically placed key grip, so the shot could keep moving through one car to the next. Think the chase scene in The Raid 2, except period comedy, in mostly idling New York traffic.

It was also one of “only two times we didn’t use an ALEXA” on the show, instead opting for the full-frame gimbalised DJI Ronin, with a “similar sensor to Sony”.

“We had two blocks of cars, basically,” and a lot of street lights he was stuck with, so Mullen “hung a SkyPanel in front of every street light (which) acted as both a light and a flag”.

He also placed “little LEDs – placemat lights” in the taxis, even “taping LEDs to the bottoms of the camera operators” as they squeezed through the cabs, “so they would act as highlights” for the on-camera faces. With all the toplighting at the location, “I didn’t want the actors’ eyes to go dark.”

Double jeopardy

Mullen at least had the benefit of being able to see all the sets of eyes he was working with at once, while he was filming them.

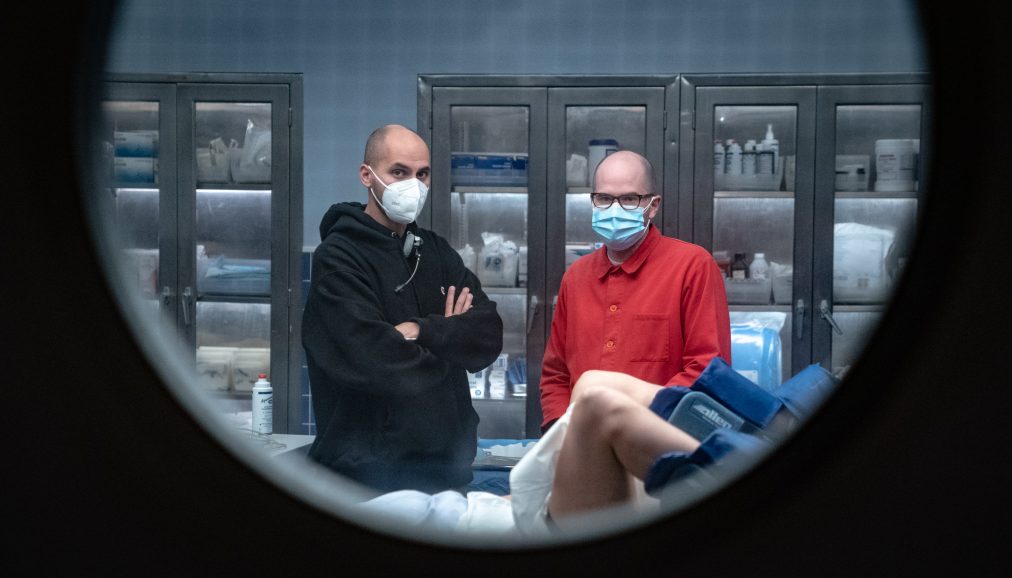

Jody Lee Lipes ASC, on the other hand, when shooting the initial episodes of Amazon’s Dead Ringers, only had one set at a time available from his lead performers. That’s because Rachel Weisz, who puzzlingly did not get an Emmy nod for her work, plays twin OB-GYNs in this remake of, and riff on, the David Cronenberg film of the same name. The twins, the Drs. Mantle, Beverly and Elliot, are hoping to find funding for a modern, science-pushing birthing centre, where bringing life into the world isn’t merely treated as an industrial process. But being derived from a Cronenberg tale (and a source novel), there are also a lot of “twin secrets” along the way, and some rather primal encounters with blood, surgical procedures, and life at either end of the spectrum.

But if Weisz was overlooked, Lipes was not, being nominated in Emmy’s Limited or Anthology Series or Movie category for the series’ first episode, One. He considers himself “lucky” that producer and director Sean Durkin asked him to come on board, extending a relationship that stretches back to NYU film school.

Lipes figures it was because he also had some “twinning experience” on HBO’s I Know This Much Is True, which featured Mark Ruffalo as twin brothers, with one dealing through a lifetime with the other’s bipolarity.

Lipes originally came on to shoot “the first three episodes that became the first two,” and then hand the reins over to DP Laura Merians Gonçalves, for whom “it was her first time doing ‘twinning’ stuff. It was nice to be able to explain it again,” he says. “I’m the kind of person that learns best when I do something twice. It really distilled the process and clarified it [for me].”

This second time around, he had some advantages compared to the earlier series, which was done both on film, and mostly locations. For Ringers, he found “shooting digitally is much easier in terms of matching lighting.” And while he acknowledges matching lighting is always a challenge when also matching each twin’s “side” of the same sequence, here “there was a lot of stage work. Having that controlled environment makes twinning much easier.”

He’s also quick to credit VFX supervisor, “close collaborator and friend” Eric Pascarelli for how convincing Weisz’s scenes are, as he “worked on the show a lot longer than I did – and Eric is so responsible for how [the series] looks,” just as he also was on the same earlier show with Ruffalo.

Lipes’ contributions to that look were captured on a Sony Venice with Panavision G Series anamorphic glass, the first time he’d been “able to use the full Venice sensor,” which he hadn’t done on The Good Nurse, the project he’d wrapped just ahead of Dead Ringers.

The anamorphics also helped him capture the look Durkin was after, wanting the show to be “stylised… and a little beyond reality”.

Which is where we came in, this month, as everyone in Hollywood and its literal and metaphorically adjacent territories, continues to feel “a little beyond reality,” as they wait for things to come back down to Earth.

That is, if this 21st century of ours still allows for such things.

See you next time, in the October country.

@TricksterInk / AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com