“The water’s risen up a couple storeys, it’s too hot to be out in daytime (and) people work by night.” If I told you that was a quote from a renowned DP, about shooting in New Orleans, you might wonder if it was someone just dispatched to record the aftermath of Hurricane Ida. Instead, it’s Paul Cameron, ASC, talking about filming the just-released “futuristic noir” thriller Reminiscence, with writer/director Lisa Joy.

It’s a collaboration that’s already proven fruitful. Joy is co-creator of HBO’s Westworld with her husband, Jonathan Nolan, and Cameron’s working relationship with the pair has gone from shooting the pilot, to subsequent episodes, to even climbing into the director’s chair on the show.

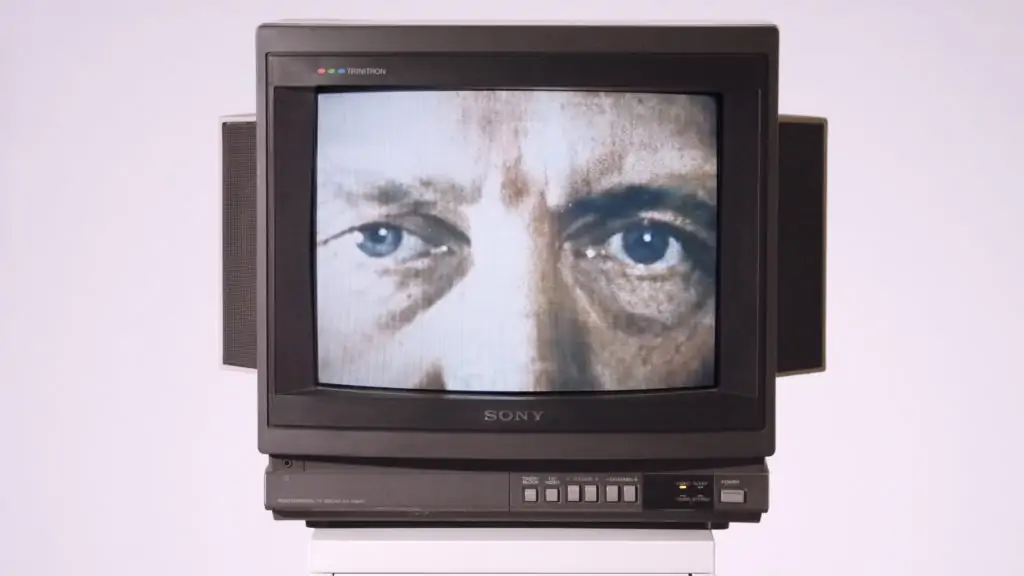

So, when it came time for Joy’s Black List-awarded script to be made, with Hugh Jackman as the two-fistedly named Nick Bannister, a “private investigator of the mind,” Cameron was the natural choice.

And there is plenty to be said about the work the always-busy Cameron did (when we caught up with him, he had just joined the Board of Governors at the Motion Picture Academy), such as his adaptation of Hologauze – a scrim-like material normally used in concert venues for projections to appear as 3D images on a 2D medium – for the rendering of the holographic memories that become Bannister’s particular back alleys. Cameron calls this breakthrough use of the material “a parallel to the (LED) volume work we’re seeing now,” in this era of “live” digital VFX.

There’d be all that and more to discuss, but happily, a more expansive piece on Paul’s work in the film is being done on Brtish Cinematographer’s magazine side, and I commend your attention to it, when that issue alights in your hands.

But one particularly striking detail came when Cameron mentioned using a deserted Six Flags park as a set – abandoned after the flooding from Hurricane Katrina, sixteen years ago, and him recalling it was “a little of a challenge to be in water, at night, in stormy New Orleans.”

Which, given recent events, would now seem like an understatement.

But it simply speaks to a challenging aspect of “near future” stories, especially ones like Reminiscence, which is set in an essentially “unusable” New Orleans, circa 2050.

That near future is here now. If Nick Bannister already had a detective agency in the Crescent City it may just have been flooded out, or had its roof torn off. While we write, many in Ida’s path are still without power, and other critical infrastructure components. And while the levees thankfully held – mostly – this time, the extent of physical and psychic damage is still being assessed.

As is the damage from the subsequent flooding of New York, New Jersey, and other areas, all of which happened as this column was being written.

The timing of all this, coincident to the film’s release, shows that what’s ahead may represent even more of a terra incognito than even some of our most imaginative minds can conjure.

Or, to paraphrase Faulkner, “the future isn’t far off. It’s not even ‘future.’”

For some, however, being routinely submerged in water isn’t a recurring facet of geography or hurricane season, but instead, vocation. Such is the case with Ian Seabrook, who is not only a director of photography, but usually an underwater director of photography, an interest that was sparked as far back as watching Sean Connery’s 007 don an oxygen tank and orange wetsuit in an attempt to stave off nuclear destruction. He became “super enamored” with how the aquatic scenes were done.

“Almost every second James Bond film seemed to have some sort of underwater sequence – films like Thunderball, and The Abyss. The amount of work involved in both those productions was just staggering.”

But also, apparently, inspiring, as Seabrook has gone on to shoot underwater sequences in films ranging from Mission Impossible – Ghost Protocol, to The Cabin in the Woods, Batman v Superman, Deadpool 2, and numerous other series and shows.

More recently, he found himself finishing up underwater photography on It Chapter Two – when a line producer on Jungle Cruise asked if he was available. He was, though it involved missing an intended Hawaiian holiday, as he instead flew to a meeting in Atlanta’s Blackhall Studios, with director Jaume Collet-Serra, some of the special effects crew, and the “dry land” DP, Flavio Martínez Labiano. Labiano had become a regular collaborator with Collet-Serra, on projects like the Liam Neeson thriller Unknown.

Seabrook wound up doing a tour, including “where they had built the puzzle-piece set,” for the film’s finale, where stars Dwayne Johnson and Emily Blunt seek to literally unlock secrets both human and botanical, near their cruised river’s headwaters.

“Some of the people (there) had done an underwater unit before – and some had not,” he says, and while the film’s submerged aspects represented “about a week and a half of work, every day there was something to do – even on our day off (like) making sure the water wasn’t being fouled by anything.”

There’s also always the business of keeping your stars alive. Seabrook recalls having “a situation where an actor lost his way, and nearly drowned. You’re the first line, you see everything.”

And while there are safety divers for the cast, on wide shots, they must remain outside the frame, which can keep them a bit farther away.

As for Seabrook, he’s usually behind eighty or so pounds of ballasted gear, underwater housings, and all. As for camera choice, he says he always “strives to use the same camera the main unit is shooting,” which in this case meant an ARRI Alexa SXT Plus, with Panavision anamorphic glass.

In this case – with Blunt appearing to dive and puzzle-solve with astonishingly long held breaths – it all went, dare we say, “swimmingly,” adding to what was a fun late summer treat from Disney.

Seabrook, meanwhile (who surprisingly, lists decidedly land-based cinematographer Robby Müller, NSC, BVK, “the master of available light,” as his own favorite) has Slumberland, a fantasy project based on the works of cartoonist Winsor McCay, coming up.

And nothing says “id” and “dreamtime” like water. Just ask Carl Jung.

Speaking of Jung (a first time for everything in this space), the psychotherapist who foresaw the rise of Naziism would likely be struck by the just-released documentary The Meaning of Hitler. Based on the bestselling book by Sebastian Haffner, the documentary, made by the married duo of Michael Tucker and Petra Epperlein, doesn’t give us another biography of the sociopathic leader’s rise to power. Rather, as its title suggests, it explores why, a hundred years after the Munich putsch (and all that followed), the personalities and atrocities of that era still have such sway on our own. Along with the concomitant grip on our imaginations, and politics.

The film follows various historians, Holocaust survivors (or combinations thereof), deniers, novelists, and more, and looks at current manifestations of Nazi worldviews in the streets of ostensible democracies.

Tucker said they “finished the movie the week the protesters were beaten and gassed in front of the White House. It feels like we’re at the beginning of something that we don’t understand – what are the forces here?” Tucker says that for him, that remains “the unsettled question.”

And like any good documentarian, Tucker and Epperlein explore answers to those questions with a stripped-down arsenal of production tools that allows more flexibility slipping in and out of war and other zones.

“We’ve always owned our own gear,” Tucker says. “If we’re out in the middle of somewhere shooting, we like to have two of the same things.” And while affordability might be one consideration, “the average audience,” he avers, “has no idea what camera package you’re shooting on.”

Which, outside the confines of columns like this, and given the ubiquity of high-end (and formerly high-end) image capturing tools now, may be a point – though the kinds of tools he uses, like Panasonic GH5s, are no slouches in that department, either.

Tucker also adds that “we don’t use gimbals for anything – I became anti-tripod. It was dangerous to carry a tripod; it looked like you were carrying a weapon.”

Those elements of danger can apply even when straddling the line between documentary and fiction, as in, say, music videos. Director Michele Civetta, of the newly released, St. Louis-set thriller Gateway, recalls starting his working relationship, and shared aesthetic, with DP Bryan Newman, on that same line.

Having met at NYU, Civetta says “we cut our teeth over the first years filming commercials in LA, and music videos. We filmed a video for Lou Reed in the barrios down in Central America, running around with undercover cops strapped with guns in red light districts and the ‘hoods of crime syndicates. Bryan and I have a certain fusion in working semi-guerrilla style with small camera bodies ala a neo-realist approach to storytelling and for some reason always find ourselves in precarious neighbourhoods. Maybe because we love street food.”

That love of street food, or more likely of precariousness, lead to what Newman calls a “neo noir aesthetic: something raw, visceral,” leading to the entirely unexpected, and entirely welcome referencing of “New American cinema classics like John Huston’s Fat City or John Cassavetes’ Killing of a Chinese Bookie.”

Unlike those ‘70s works, these shades of noir were captured on an Alexa Mini, sporting vintage Cooke Panchro lenses, “and an incredible LUT that my colourist Mark Wilenkin and I developed before production. The Mini’s compact design and light weight also allowed me to work handheld for the majority of the film…with the freedom to improvise with the actors in real time.”

And if improv is the art of capturing the intangible, it serves as a reminder that the seemingly separate disciplines within visual production may not be as disparate as we thought.

Consider the way Emmy-nominated sound mixer Alexandra Fehrman talks about her work – and about colour – on The Boys:

“Many people talk about sound in colour since sound is such an intangible thing. Using words to describe it is different for everyone. Directors and EPs will often use feelings to describe what they want from sound, or reference big scenes from past films.”

And if you remember last column’s talk about The Boys’ VFX and that department’s work with cinematographers, you may remember mention of a certain beached whale. Well, Fehrman had her cetacean encounter, too: “Both (fellow mixer) Rich (Weingart) and I played with and refined a specific reverb for what the inside of a whale carcass might sound like. We let the visuals of how the whale was designed inform us as to what type of space we were working with.” Just like lighting! “Many times the visuals direct sound, and we are building the environment to help the viewer immerse themselves in it.”

And in a time of so many unwelcome “immersions,” who could blame anyone for wanting to secret themselves away, Jonah-like, inside a whale – at least for a little while?

Meanwhile, our correspondent will likely be immersing himself inside a live Emmy press room this month as well. Like so much now, it will doubtless be familiar and strange, all at once.

More in October. @TricksterInk / AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com