Stealing Hearts

Sean Bobbitt BSC / Widows

Stealing Hearts

Sean Bobbitt BSC / Widows

BY: Trevor Hogg

Upon graduating from Santa Clara University in California, Sean Bobbitt BSC headed back to England believing that he would go straight into directing television shows.

“Everywhere I went, people were kind but laughed as the average age for a director was 35 to 37. After about six months without a day’s work, and absolutely penniless, I was offered a job as a freelance news soundman for CBS, but a year later we both agreed that I should be doing something else. I told CBS that I could shoot, but didn’t hear anything from them until the Falklands War broke out as there weren’t enough cameramen in London. For 10 years I did mainly freelance work for CBS and just about everyone else based out of London. All of the time I was still thinking that I’m going to write and direct that perfect script, but it wasn’t quite happening. I moved into documentaries, which I felt were more interesting and challenging. Then I literally woke up one day and thought, ‘Wait a minute I’ve been shooting for 18 years. Maybe this is what I should be doing!’ I did a seminar with Billy Williams, who is an amazing teacher and cinematographer at the International Film and Television School in Stockport, Maine and by the end of the week I knew what I was going to do for the rest of my life – be a cinematographer.”

A fruitful collaboration was established a decade ago between the transplanted Texan with an acclaimed British video artist making his feature directorial debut. “I hadn’t done that many feature films before Steve McQueen and I started on Hunger. I tend to do two feature films a year, whereas Steve has done one every three years. We are good friends and keep in touch. We both bring back more into each subsequent film because of the experiences that we had between them.”

Following Shame and the Academy Award and BAFTA Award-winning 12 Years a Slave, the creative duo have partnered for a big screen adaption of a ground-breaking British miniseries released in 1983 about a group of women attempting to pull off a heist planned by their deceased husbands. “Steve first mentioned Widows to me a decade ago. We’ll have a casual conversation, discuss it a little bit, he’ll disappeared for a number of years, and then come back and make a comment about it. All of that time, Steve is consciously and subconsciously working on, exploring and figuring out that idea. Initially, it’s the gut emotion that he feels. As a child Steve watched the original Widows, which was the first TV drama on the BBC that had women in the lead roles and was written by a woman. Everyone watched Widows so it was talked about and discussed. Steve was never quite sure why it specifically stuck. Even as we were filming Widows, some days he would say, ‘There’s something here. I’m not sure what it is but it’s really good.’”

“As the script got developed for Widows we started talking about different ideas and possible visual influences that would lead us in the right direction to tell the story,” explains Bobbitt. “Steve is always presenting me with works of art not for colour or composition, but for the emotion that they convey. We looked at epic American films and one that kept on popping up was Chinatown. It was more about how the story progressed, strong compositions, confidence in the actors for holding the scene and simple camera movements.”

All of the films directed by Steve McQueen have been shot in the 2:40:1 aspect ratio. “We wanted Widows to feel epic. The 2.40:1 aspect ratio lends itself to a sense of scale. Also, when you get groups of people together in a scene, 2.40 gives you so many more possible compositions that holds everyone. Depending on where you place the character within the frame it can change the emotional affect that the audience has to that character. By being slightly below the eyeline you can make a character incredibly powerful, and by pushing them right off to the side and being slightly profiled they can appear rather ominous. Both Steve and I find it to be the most exciting aspect ratio to work with and also the most effective in terms of storytelling.”

Only the stunt scenes had storyboards. “The general day-to-day running is we arrive onset, I’ve done a pre-light of the location already, the set is cleared, the actors come in and rehearse with Steve, when they’re happy I’m called in, we look at a blocking, and Steve and I quickly breakdown the shot there and then,” reveals Bobbitt. “We don’t like the word coverage. What we try to do is determine the specific shots needed to tell the story. If we can make it work in one shot we’ll make it work in one shot. If it needs two shots, we’ll do two shots. If it needs more, then we’ll do more.”

One camera operated by Bobbitt was used for everything except for the explosion of the van. “Once you start putting second and third cameras in then the prime position for a camera to be in will be compromised because you don’t want to be in everyone else’s shot. You don’t need more than one camera if you understand the story, have good actors, and are willing to take the risk that you will get the shots needed for the scene.”

A documentary approach is taken as the camera responds to the actions of the actors. “Steve and I find it that much more engaging if the audience has to pay attention in the same way the actors do in what’s going to happen next,” notes Bobbitt. “We used the ARRICAM LT and ST in 35mm 4-perf, a 2.40 extraction using spherical lenses, primarily Cooke S4. The beauty of the Cooke S4 is that they have a slightly lower contrast and a touch of warmth that I find appealing mainly for portraiture work but at the same time are sharp; that contradiction is appealing and works beautifully on the human face. The Cooke S4 also drops off more quickly than some of the other lenses of the same focal length.”

The lenses ranged from 14mm to 350mm. “A lot of the time I was working with 40mm and 50mm. For the handheld stuff, 27mm and 32mm were my favourites.” All of the camera equipment came from ARRI CSC, which is part of the ARRI Rental Group in New York.

The lighting equipment came from various suppliers in Chicago. “We didn’t want the lighting to be too stylized, as the audience had to believe that these are real people in real places,” remarks Bobbitt. “But if you have a scene that is eight pages long, you have to be able to freeze that light in that period of time so you can’t use available light.” Principal photography started on May 8, 2017 in Chicago. “It’s incredibly changeable the weather. Not just day to day but minute to minute.”

A large mix of lights were utilized. “I’m using more LEDs because they’re lighter, more efficient and the quality of light that you get is wonderful. We used some China balls with the old-style incandescent bulbs and large HMIs for the daylight fill. Some of the locations were enormous, so some of the lighting setups were substantial but hopefully nobody will notice that.” Powerful lights were needed for a scene when Jatemme Manning (Daniel Kaluuya) kills two of his thugs. “We had six 18Ks coming in through windows with a big scaffold outside to light the basketball court as if it were happening in the afternoon.”

Footage was captured on Kodak Vision 3 50D 5203, 250D 5207 and 500T 5219. “The 50 Daylight has an amazingly fine grain structure and there is a depth of colour to it that is so rich and vibrant for the daytime exteriors of Chicago,” explains Bobbitt. “It’s also wonderful on the darker flesh tone. The 250 Daylight gives you enough exposure for your daylight interiors. It has nice flesh tones, a low grain and cuts well with 50 Daylight. The 500 Tungsten was used primarily for nighttime interiors and exteriors. For the exteriors, I’m using a lot of the available light so I’ll push it to 1000 ASA. I push it one stop in the processing. There’s almost no visible grain increase in doing so. It’s a flexible stock. It has beautiful rich blacks. There’s a lot of latitude with it. The thing that people don’t realize, is on a film you have three different colour layers so you’re getting a lot of information in the red, blue and green on every single frame. Whereas on a digital camera, you only have surface of the chip, so what you get in each pixel is what you get.

Colourist Tom Poole at Company 3 is the best in the world and knows how to find the hidden stuff in the negative.” Bobbitt adds, “There’s this crazy battle going on about 4K versus 6K versus 12K. At the end of the day as a cinematographer, I’m much more interested in colour information and exposure latitude.”

"We don’t like the word coverage. What we try to do is determine the specific shots needed to tell the story. If we can make it work in one shot we’ll make it work in one shot. If it needs two shots, we’ll do two shots. If it needs more, then we’ll do more."

- Sean Bobbitt BSC

Locations are a crucial part of the storytelling. “They inform so much of the composition and encourage the movement of the actors,” notes Bobbitt. “We were lucky to be working with [production designer] Adam Stockhausen [The Grand Budapest Hotel] again, who has a magnificent eye, comprehension of story, and how location tells story. We had quite a lot of prep period specifically so we could find and tailor each individual location so that the story is being constantly reinforced by where it’s actually happening.”

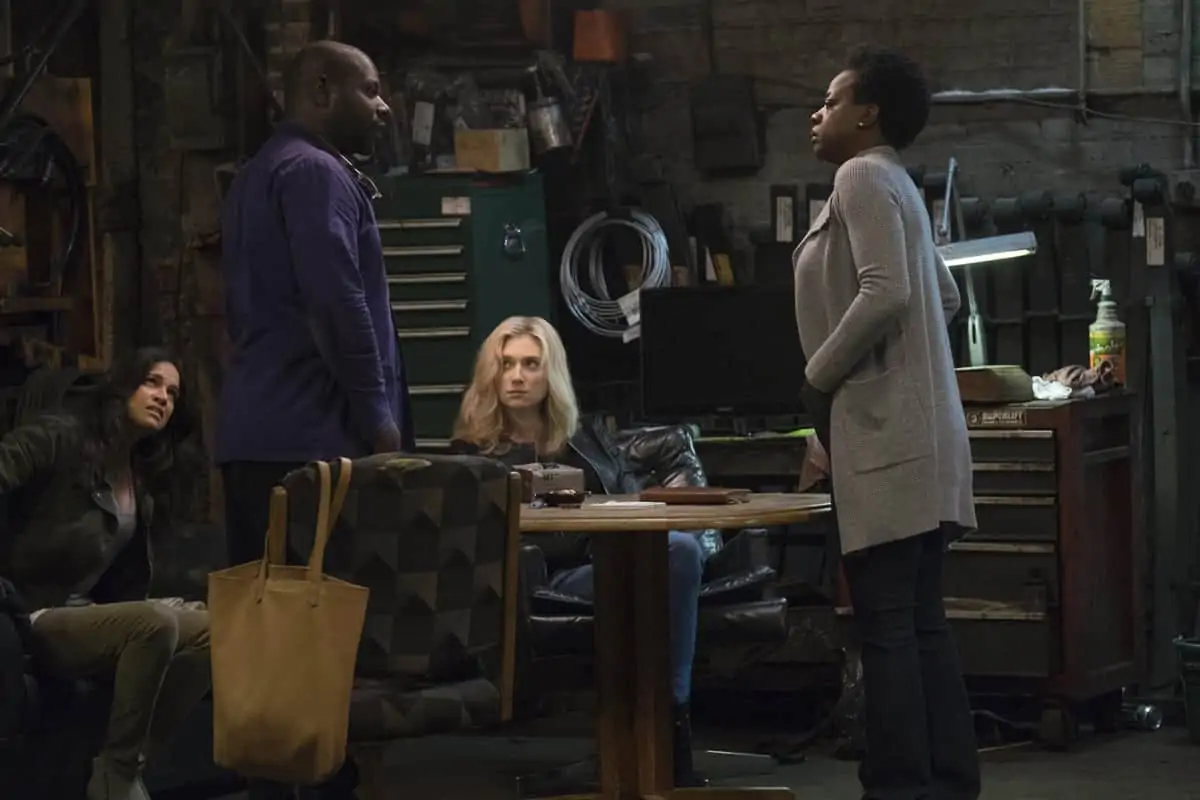

A key setting to find was the warehouse where the deceased spouses of the widows plotted their heists. “It had to be a space that spoke of their husbands constantly so there was that element of a reminder that they’re moving into their husbands’ shoes. Adam went through and refined it beautifully.”

“Chicago is a fantastic city,” notes Bobbitt. “The complexities of it socially, politically, and economically are fascinating. It is America writ large in a small space. Chicago has an incredible history and culture in terms of the architecture, art and music. You also have great wealth and poverty literally side by side, cheek by jowl.”

Widows was shot primarily on location. “Mulligan’s house where the heist takes place - it had to have specific elements, and took a lot of effort from the locations and art department to find the place where everything worked and we could have access for a long period of time. The house was gutted and redressed so we could use almost every single room in it for those sequences.”

A continuous two and half minute shot emphasizes the close proximity between the wealthy and poor. “The Jack Mulligan [Colin Farrell] character, who is a politician, gives a speech in a poor rundown area and then gets into his car and drives home,” explains Bobbitt. “We’re outside the car that has tinted windows so we only hear conversation between Mulligan and his assistant Siobhan [Molly Kunz] but we see the slow transformation from poverty to wealth in real-time.”

The main challenge was logistical. “You’re in a moving car which is being towed by a tracking vehicle that has a Technocrane on the back of it. From the moment that they get into the car to the moment they get out of the car, you have to ensure that there is a free flow of traffic. There are lots of moving parts there. But if you do your homework, rehearse it - which we did a number of times, work out all of the kinks and give it a go, then you’ll get it in the end. I did two or three takes. It’s all about anticipating what the problems are going to be and have solutions for them before you’re there on the day.”

A long Steadicam shot takes place during the basketball court scene. “We wanted to do something like that but didn’t know that we could do it until seeing a rehearsal,” states Bobbitt. “We had a great Steadicam operator, David Chameides, who worked for us on Shame. Whatever you ask him to do, no matter how impossible it is, David figures out how to do it. There’s a wonderful ballet between the Steadicam and the actors which ends with a moment of high violence.”

A lot of thought goes into how violence is going to be depicted. “Some of it is straightforward and technical. How explicit should it be? Do we want exploding heads and blood? How are we going to achieve that? A lot of the time, the idea is not to glamourize the violence but to make it as real as we can. One thing that Steve and I have discovered over the years, is by using a long continuous shot in association with violence, it takes you away from the conscious idea that you’re watching a movie. As the audience, you’re drawn deeper into the action by the lack of the cut. If you don’t put a cut in then you have no escape, so the violence compounds itself to great dramatic effect.”

A key crew member for Bobbitt was first camera assistant Chris Flurry. “Because I operate as well as light, the running of the camera department is left to Chris and he’s also an amazing focus puller. The gaffer was Bill Newell, who did Shame with us and is originally from just outside of Chicago so knew the place and the players. Bill knows how Steve and I work and what the expectations are so he’s a step ahead of the game. We were fortunate to have a fantastic key grip, Art Bartels, who is also a Chicago native but has worked all over the world. I hope one day to have made half as many great films that Art has worked on. Then there are the people who come with them, the rest of the lighting, grip and camera crew; these are the people who are the heart and soul of the film. We had a fantastic crew in Chicago. If you have a crew that’s hard working, openminded, and maintains a good sense of humour and comradery, then the days go faster, you shoot more, and you end up with a better project.”

Other notable contributions came from dolly grip Kelly R. Borisy, second camera Chris Whittenborn, second assistant camera Summer Marsh, film loader Matt Hedges and David Chameides who operated Steadicam and photographed second unit beauty shots of Chicago.

Widows stars Viola Davis, Michelle Rodriguez, Elizabeth Debicki, Cynthia Erivo, Robert Duvall, Liam Neeson, Colin Farrell, Brian Tyree Henry, Daniel Kaluuya, Jacki Weaver, Carrie Coon, Lukas Haas, and Molly Kunz.

“You couldn’t have asked for a more stellar group of actors,” enthuses Bobbitt. “The beauty of working with Steve is that great actors want to work with him, and as you watch the film there’s not a weak performance in there. They feed off of each other. I consider myself extremely fortunate as the operator because I’m the first set of eyes that these performances go through and so many times on this film I could feel the hairs standing up on the back of my neck thinking that, ‘Wow! This is something special.’”