Kung Fu Fighting

Roger Pratt BSC / The Karate Kid

Kung Fu Fighting

Roger Pratt BSC / The Karate Kid

Trailblazing cinematographer Roger Pratt BSC spent five months last year filming Columbia Pictures' remake of the classic '80s The Karate Kid, and spoke to Ron Prince about his favourable experiences with the resourceful local crew.

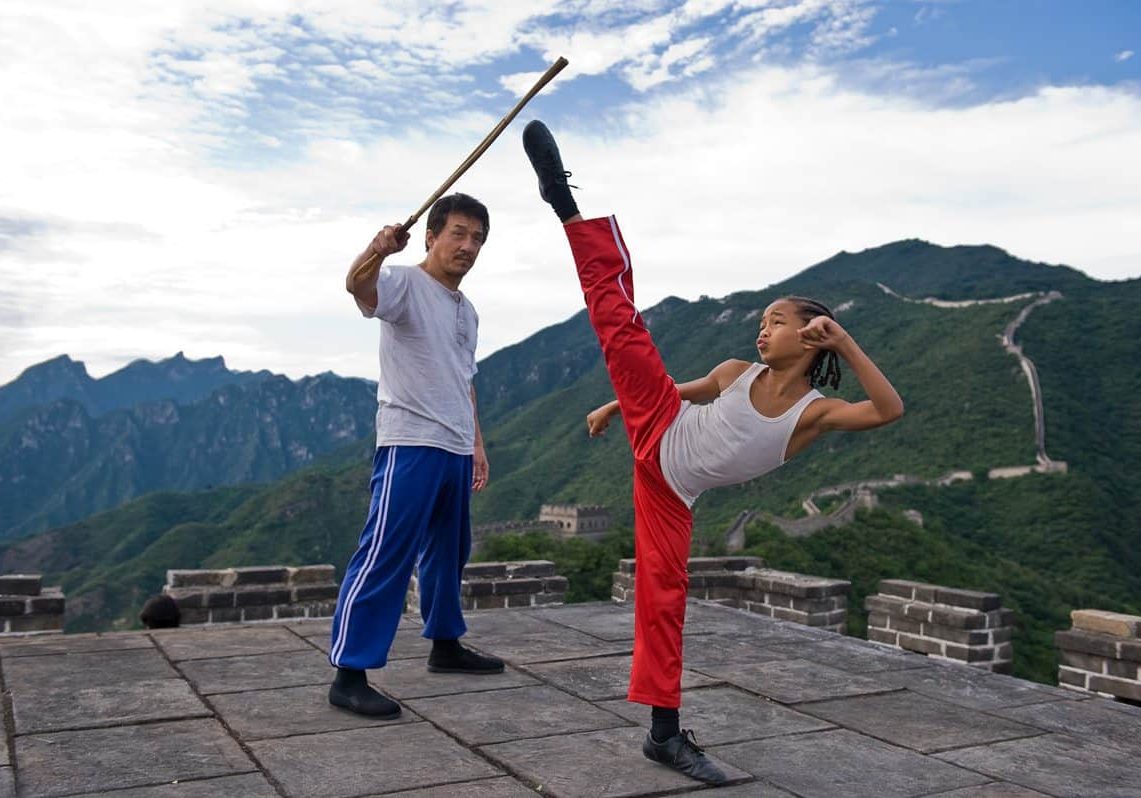

The Karate Kid, known as The Kung Fu Kid in China and Best Kid in Japan and South Korea, is the 2010 martial arts remake of the 1984 film of the same name. Helmed by Norwegian director Harald Zwart, produced by actor Will Smith and his wife Jada Pinkett Smith, the remake stars their 12-yearold son, Jaden, and martial arts legend Jackie Chan. The film was produced for Columbia Pictures through Smith's Overbrook Entertainment, in association with China Film Group and Jerry Weintraub Productions. Principal photography, under Roger Pratt BSC's auspices, took place in old and new studios in Beijing, and on location in the Wudang Mountains, between June and October 2009.

The new The Karate Kid keeps much to the same formula as the original, but with an oriental setting instead of California. Dre Parker (Jaden Smith) moves to China with his mother Sherry (Taraji Henson), when the car manufacturing plant in which she works is relocated to Beijing. Although Dre misses Detroit his mother tells him that China is home. He begins to like China when he falls for his classmate Mei Ying (Wenwen Han), but the romance is nipped in the bud by Cheng (Zhenwei Wang) the class bully who puts Dre to the ground with ease using his Kung Fu training. However, Mr. Han (Jackie Chan) the maintenance man, secretly a Kung Fu master, teaches Dre and, armed with this new skill, he eventually faces down Cheng in a Kung Fu tournament.

Pratt's involvement in the film came through the Norwegian director Zwart (One Night At McCool's, Pink Panther 2), whom Pratt has known for a decade working on commercials – one of the most memorable, Pratt recalls, a Lurpak butter ad for which he had to transform a snowbound, winter, Norwegian landscape, into to a French summer idyll using snow-ploughs and lashings of hot water.

Pratt's feature credits include The End Of The Affair, for which he was Oscar-nominated, and Chocolat, for which he earned a BAFTA nomination. He also lit Terry Gilliam's seminal Brazil, Twelve Monkeys, Wolfgang Petersen's Troy, and Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets for Chris Columbus, and Harry Potter And The Goblet of Fire, for Mike Newell.

"Harald was aware of my motion picture work, such as Chocolat, and when he landed The Karate Kid wanted a friendly face on board, with experience of shooting big pictures," comments Pratt. "The mantra with Harald was 'up close-and-personal ‘so we shot a great deal of Steadicam."

For reference, Pratt says he watched the original trio of films. "They were shot in original Technicolor, 12ASA film, and the things they were able to do then were not subtle. It was hard for DPs just to get good exposure I think, especially on an action-packed film like this, and they would always have had a Technicolor technician looking over their shoulder on set too. We have much more flexibility and subtlety now with cameras, lenses, lights and filmstocks. For example, in the denouement scenes at the Kung Fu tournament, we had lights blasting from all sides and above, multi-camera set-ups, a Rock & Roll lighting rig that had been left over from the Olympics."

Of course, when your shooting in uncharted country it pays for have a good wingman, which Pratt discovered in the guise of unit production manager Dany Wolf. "Dany was pivotal in making it all work. He speaks fluent Mandarin. He's a grafter, and very persuasive. His job was to find and get permission for all the sets. Not easy for places like Tianenmen Square! In the end the Chinese always came up with the goods."

Pratt also found an excellent resource in Fiona Qi, the best boy. "She is fluent in English, very technical, cinematography oriented, and very nice with it too. Absolutely indispensable."

Early on in the prep stages, Pratt needed a top gaffer from the UK, Tom Finch (brother of Chuck Finch), "who did a superb job. During what proved to be a really long shoot, we kept each other sane and on track."

Pratt praises the handheld work of Hong Kong camera operator Man-Ching Ng, and Jai Yip Siu Ching, who wielded an Alien Revolution rig during the many fight sequences, "a brilliant steadicam operator, very sensitive, and I would use him again."

Pratt went to Beijing for a week during May 2009, to look at the possibilities for shooting there. "Dany wanted me to scout around at facilities, kit houses and studios. I have to say I was impressed – it had all of the basics for a big picture, but not much specialist lighting equipment at the time. They had all the latest HMI lights, but still in their crates! During my time there, when expertise or equipment was required, their first turn was to Hong Kong, where they have been making feature films for world market for a long time."

Amongst the surprises on the studio front was Beijing Film Studios, around an hour's drive out of Beijing, offering nine stages, one being the size-equivalent of Shepperton's mighty H Stage, an outlet of ARRI lighting and camera equipment, and a backlot with local environments and lakes.

"It was brand new and beautifully done," says Pratt. "The stages have earth floors, so you could build a set on top of that to suit your needs."

Closer to the city, where the main production offices were sited, was an older, smaller and somewhat run down studio, but adjacent to this was a quartet of traditional village dwellings facing onto a communal quadrangle courtyard – Mr Han's home where he teaches Dre the art of Kung Fu.

Illustrating Chinese determination to help, Pratt recalls how Zwart came up with the idea of filming shadow play at night of a typical lesson, supposedly lit by a car headlight, playing on the walls of one of the buildings in the courtyard. Pratt knew he would need an open brute to create the hard-edged shadows.

"The request immediately caused quite a bit of consternation, as the Chinese have got rid of their old equipment, and all they have are HMIs," he says. "But low and behold Tom and Fiona found one in Hong Kong. We fired it up, and the shadows were so beautiful and sharp that Harald got inspired and wrote some extra scenes."

More helpfulness came during a five-day jaunt to film in the Wudang Mountains, two hours flight south of Beijing, in the northwestern part of Hubei Province known for the many Taoist monasteries and its association as a centre for martial arts.

"It's very different to Beijing, with beautiful countryside, spectacular scenery, and 2,000ft to the top," says Pratt. "Logistically, it seemed it might be a difficult place to film in, but if we asked for a 5Kw generator, some of the crew would run up with it. Nothing seemed to be a problem getting kit from bottom of mountain to top. It was hard to perch beside a temple on a sheer face, with cranes to look inside, but we managed it."

One concern at an early stage was the weather, as a significant amount of the production was due to shoot outside. "I will never forget sitting in pre-production one morning, and all of my preconceptions that shooting in China the weather would be lovely everyday, suddenly vanished as a storm came rumbling in. At 11am in the morning it was almost as black as midnight, and it absolutely poured with rain until 4pm in the afternoon. I knew we'd have to find a way of maintaining the continuity of lighting on the main exterior/interior set during production," he recalls.

Pratt devised what he terms a 60 x 60 x 60 Toblerone-rig, reinforced to carry the HMI and tungston lighting, which meant that should the daylight prove inclement, the production could carry on regardless, and could also be used for nightime sequences.

Concious that the sun moves one degree every four minutes, he also found himself deploying a huge silk, suspended over Mr Han's courtyard by a massive crane, which could provide various strengths of cover as required, but also able to give reasonably consistent soft fill-light.

As to the framing of the production, Pratt says it was a very quick discussion. "We didn't want to shoot Anamorphic, as those big lenses would have slowed us down. Harald likes to work fast and light, but wanted the elongated frame, so we went with 2.35:1, shooting 3-perf, which also saved us a bit on the stock, although there was an unforeseen drawback when it came to seeing the rushes.

Pratt selected ARRI LT cameras fitted with Cooke S4 lenses, using Primes for the many handheld or Steadicam fighting sequences, and Cooke's 40-200mm zoom for the rest of the film. Film stocks included Kodak daylight and tungsten stocks, about which he says, "with everything being one step further away than normal, we had to be a little bit more careful when ordering."

Processing was handled at the Kodak-owned Cinelabs Beijing. Although the director and producers watched rushes on their iPhones, Pratt was afforded the luxury of viewing some projected rushes, albeit in slightly compromised circumstances. No local cinema could screen the 3-perf rushes, but a large dubbing suite about an hour out of the capital was found. Despite the projector over-filling the screen, as it had the wrong lens for 3-perf, Pratt says he was able to get some idea of how the rushes were working out.

Overall, the experience was so good that Pratt says he would not be surprised to find other major productions finding a base in China.

"Beijing is a massive city, with an impressive modern infrastructure – beautifully-designed roads and flyovers, a foreign friendly underground system where the announcements are made in English as well as Mandarin, an Olympic gift, plenty of foreign shops and very nice hotels. Ten years ago, it would have been very different, but modern China is more westernised and, in terms of the film industry, very welcoming. The Chinese want to get on the world stage more in every walk of life. We were a big production, and despite a few hiccups along the way, they were hugely accommodating and handled it really well."