CHASING SHADOWS

Carol Reed’s 1949 masterpiece The Third Man, starring Orson Welles and Joseph Cotton, returns to cinemas in a 4K restoration, showcasing innovative cinematography by Robert Krasker BSC.

After 75 years, the story of a black market racketeer, Harry Lime, played by Orson Welles, and friend, the naive pulp fiction author, Holly Martins, played by Joseph Cotton, still garners attention. It was hailed as a masterpiece when it premiered in London in September 1949 – and was an international success, winning the Best Film BAFTA, the Grand Prix at Cannes and an Oscar. In its 75th year, The Third Man is back in cinemas after a 4K restoration by StudioCanal.

Carol Reed’s film of Graham Greene’s story was innovative. It was filmed extensively, but not entirely, on location in bombed-out Vienna. It used major Hollywood talent but was predominantly a British production with input from Hollywood titan David O Selznick. It also had an anti-American and anti-establishment theme. Perhaps the most lasting innovation was the visual look of the film and the sharply angled photography.

The deliberate distortion of the level horizon line in the film frame is called a canted or oblique angle. It was and still is called “a Dutch Tilt” in the British film industry. It is mainly associated with German expressionist cinema. It was given the name Dutch via an awkward translation of the German word for “German”, Deutsch. In British and Hollywood films, Alfred Hitchcock was the most notable exponent of the Dutch Tilt in his films, after spending time at the start of his career at the German Studio UFA. His most significant uses are in the films Suspicion (1941), Notorious (1946), Strangers on a Train (1951) and The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). The Third Man is often associated with this technique and is widely regarded as the film that makes the best use of the method to add to the story and drive the narrative.

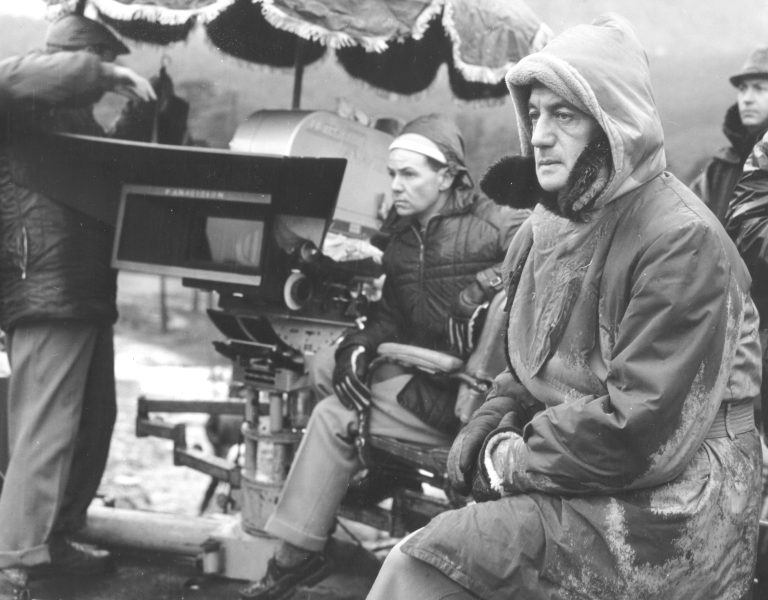

Director Carol Reed knew the look he wanted for The Third Man, and his first and only choice would be his cinematographer from Odd Man Out (1947), Robert Krasker BSC. Krasker had lit locations in Belfast, Northern Ireland, for Odd Man Out in black-and-white and was up to the task of creating the evocative shadows in the boomed-out grandeur of post-war Vienna. He used the Dutch Tilt technique to create a startling effect.

On The Third Man, so compelling was the tilting camera angles that legendary filmmaker and close friend of Reeds, William Wyler, gave Reed a spirit level and a note reading, “Carol, next time you make a picture, just put it on top of the camera, will you?”

In a later interview, Reed revealed what he was trying to achieve photographically. “I shot most of the film with a wide-angle lens that distorted the buildings and emphasised the wet cobblestone streets (it cost a good deal to constantly hose them down). The angle of vision was just to suggest that something crooked was going on. I haven’t used it much since, only to shoot someone standing behind another person who’s sitting, and I don’t want to cut off his head.”

In a 1972 interview, Reed told Charles Thomas Samuels about the emotional effect of his camera techniques. “I hope it’s not noticed by someone less familiar with pictures than you are. I intend it to make the audience uncomfortable.”

Krasker was born in 1913 to Australian parents in Alexandria, Egypt. He moved to England in 1932 and became a camera operator for Alexander Korda’s London Films, working on The Four Feathers (1939) and The Thief of Bagdad (1940). He received his first assignment as a lighting cameraman or director of photography on the film The Saint Meets the Tiger in 1941. Before working for Reed on Odd Man Out, he would light Henry V (1944) for Laurence Olivier and Brief Encounter (1945) for David Lean. Krasker’s opening shot from the film remains and is praised for its cinematic bleakness as Pip runs across the marshes, almost silhouetted by the night sky and river behind him.

Krasker would win an Oscar for his work on The Third Man and later have great success with the historical epics Alexander the Great (1956), El Cid (1961), and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). Krasker was a founder of the British Society of Cinematographers in 1949. Director Martin Scorsese says, “You can’t talk about The Third Man without recognising the incredible contribution of Robert Krasker’s photography. The night scenes, the streets wet down and the city ruins. An extraordinary sense of the world has come apart, particularly the tilted cameras. The camera style visualises it for me; there’s no settling of the camera, and you don’t feel grounded. It reflected what was left of Vienna. People live in beautiful apartment buildings, but simultaneously, the camera would pan and destroy it. The images never feel grounded.”

When Krasker died in 1981, filmmaker Bruce Beresford wrote, “From the beginning, his style was distinctive and remains quite undated when his films are screened today. He eschewed glamour in favour of realism and was noted for his extraordinary use of high-contrast images and bold wide-angle compositions.”

This article appears in The Third Man: The Official Story of the Film by John Walsh.