PAINTING TERENCE DAVIES’ POETRY

You wouldn’t associate filmmaker Terence Davies with VFX. His films are fluid but sedate, his compositions painterly, the structure and content tending to the poetic. Yet in Benediction, a drama based on the life of solider and poet Siegfried Sassoon, his interest in blending classical with digital technique comes to the fore.

“I went in with the idea of Terence being this classic poetical filmmaker and what I found really exciting was his embrace of VFX to achieve his vision,” says Nicola Daley ACS.

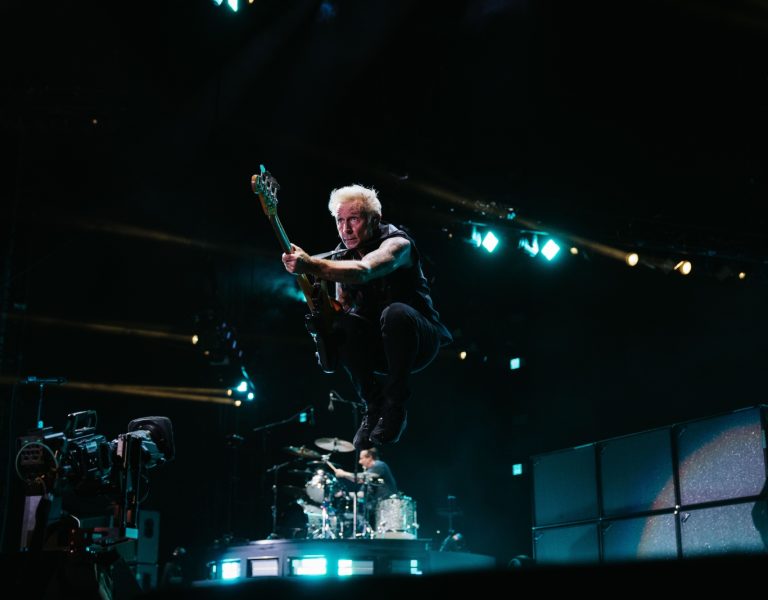

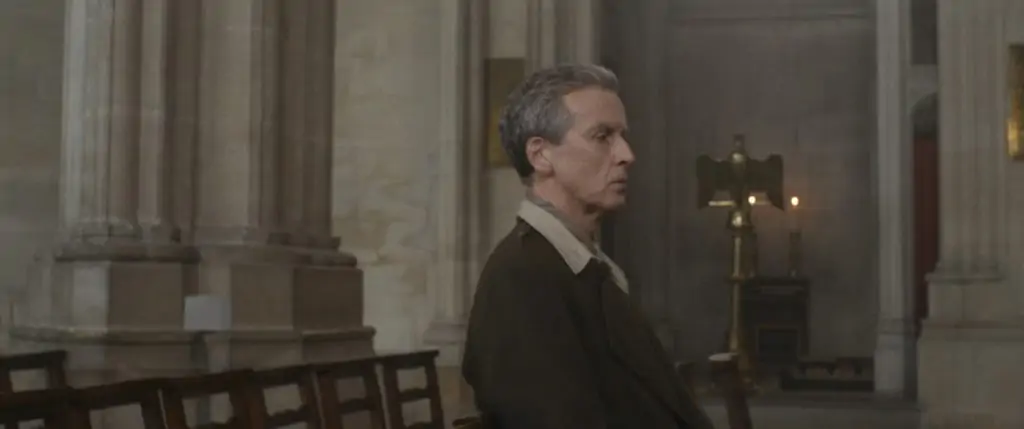

A case in point occurs in the first third of the film where actor Jack Lowden, playing the younger Sassoon, morphs into the older Sassoon, played by Peter Capaldi. It’s a scene depicting Sassoon’s conversion to catholicism and was shot in Downside Abbey, Somerset – the same cathedral where Sassoon was admitted to the faith in real life.

Login to continue reading

This content is exclusively for digital magazine subscribers.

Start your subscription today, or login below to continue.

“I lit the space to film a 180-degree arc in the middle of which is the morph between young and older character,” Daley explains. “It’s an idea that Terence took from his previous film A Quiet Passion but extends here using a moving camera on a motion controlled MRMC Talos rig. It’s quite a bold melding of modern VFX and classic filmmaking devised by Terence and worked out by me with VFX supervisor John Paul Docherty.”

Daley hadn’t worked with the director and screenwriter of Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Deep Blue Sea but had long admired his work. At interview with Davies and producer Michael Elliott, she says they talked about old films.

“We got along really well. I’d been sent the script which Terence told me he’d spent five years writing. He’d done a lot of research into Sassoon’s life. The story spans 1914 to the early sixties but it’s not a traditional biopic. It’s more thematic, nonlinear, going in and out of his time periods, about Sassoon’s search for meaning in his life.”

Ahead of her interview, Daley assembled a pitch document of stills from films and paintings. Davies skipped straight to the paintings. These included CRW Nevinson’s depictions of WW1 “for the colours of uniforms and battlefield backgrounds,” Walter Sickert’s post-impressionist paintings of theatre society and period portraiture by David Jagger and John Singer Sargent.

“We also looked at the photography of Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) for scenes in the beginning of the film before Sassoon goes off to war – in particular for the look of blooming highlights of street lamps in a foggy London.”

There were, though, two films that Davies specifically referenced for look. Powell and Pressburger’s timeless ballet drama The Red Shoes and David Lean’s This Happy Breed, adapted from Noël Coward’s play about family life between the two World Wars. Released in 1944, This Happy Breed was shot on three-strip Technicolor stock but in a way that defied convention.

“Lean was obliged to have a Technicolor representative on set, but he ignored them,” says Daley, who did her own research on the film’s production. “Because he wanted to show life for the family as being hard, Lean drained a lot of the jazzy Technicolor look, except in scenes of celebration and bunting decorating the street when the Technicolor bursts into life. That was the touchstone for what Terence wanted for Benediction.”

Camera tests with costume and make-up helped her devise a LUT inspired by This Happy Breed with Lipsync colourist Jamie Welsh. “The LUT is muted but with warm skin tones. I’ve done lots of blocks of TV shows (S2 of The Letdown for Netflix, S3 of Harlots for Hulu) where you inherit a lot of LUTs, and it can get complex. I prefer to keep it simple.”

The budget didn’t allow for a 35mm shoot but Daley was more than happy to return to the Sony Venice which she had previously used on episodic show Paradise Lost for Paramount.

“Terence prefers traditional mid-shot singles to over the shoulder shots so I thought skin tone would be important and Venice has beautiful skin rendition. I chose Cooke Speed Panchros (also hired from Movietech) as older spherical lenses that leant the image a softer look. At Terence’s suggestion I cropped for 2.39:1, an aspect ratio he had liked on A Quiet Passion.”

Daley used Tiffen Glimmerglass diffusion for pre-war scenes and removed it for a harsher look when Sassoon is in war hospital Craiglockhart (where he met budding poet Wilfred Owen).

She also used a variety of gels. “Before the War, when we’re at the theatre with Sassoon and his brother and we see his mother waving him off to the front, I used Vittorio Storaro’s Cyan Cinegel. It offers a slightly greener-blue colour for the moonlight.

“The way Terence writes and edits means the story is not operating in the realm of realism. He is transposing one time period to another. That’s why I think a degree of theatricality in colour and lighting works.”

At the end of the film there is another use of VFX which required previz. In the scene, Sassoon is at the christening of his child and asks his wife to dance. The camera moves around the couple, looks into a mirror and moves into this ‘mirror world’ where Sassoon is seen (imagining) dancing with the other significant loves from his past.

“As a concept it took a while to figure out,” Daley says. “We shot the first part up to a real mirror on Steadicam (VFX plates required) and the mirror world was shot against green screen with the camera following an identical track for each of the couples. I kept the lighting the same, but it starts with a warmer colour temp and with each successive couple it gets cooler. It is very poignant and sad as we feel his sorrow at all these loves lost.”

Benediction was shot entirely on location including at stately homes Chillington, Hagley and Himley Halls (all in the West Midlands), Redditch theatre (interior) and Leamington Town Hall (exterior). Photography was delayed from March until September 2020 with scenes finessed with Davies over Zoom.

“He doesn’t even have a mobile phone so getting him on Zoom was a treat in and of itself,” Daley relays. “He has never before used Steadicam, but I showed him showreels of operators (Dan Edwards, Tom Wilkinson, John Hembrough) whom I thought he would get on with – and he jumped at the chance!”

Another scene showing boys and girls in a park voiced to a Wilfred Owen poem was shot Steadicam. “It was at dusk and we used some poly to bounce light and he loved the fluidity of it. I’m not sure he’d experienced that before. It was beautiful to watch him so joyful at the new experience.”