ORGANIC MATTERS

Nancy Schreiber ASC’s choices as a filmmaker reflect her choices in life—find your passion, follow it, and don’t look back. The cinematographer shares highlights from her varied and extensive career and explores her love of the craft.

“I went from job to job, taking some assignments that were not great or not well-paid because I just wanted to shoot; that’s how I learned.”

Nancy Schreiber, ASC is someone who goes by her instincts. Her choices as a cinematographer reflect her choices in life—find your passion, follow it, and don’t look back. In her eclectic decades-long career, she’s shot narrative films, television series, commercials, music videos, and documentaries, and has never shied away from taking on projects that were, as she says, “not great” because you never know where something can lead. It’s been an almost innate part of her life from a very young age—letting the art take her organically from one part of her life to the next. She calls it “controlled chaos.” And, looking back, there have often been disappointments at not getting hired on certain projects she wanted or thought she’d be perfect for, but she kept going, always reverting to her love of the artform and the roots that it came from.

“My interest in visual mediums started with my family,” says Schreiber who was born in Detroit, Michigan. “Growing up, I saw my mother work as a docent at the Detroit Institute of Art as well as discovering up-and-coming artists in Chicago for her interior designer friend’s assignments. My dad was a commercial roofer and had a terrific design sense; he designed the house we lived in.”

When Schreiber was 11, her father passed away after a long illness and her artistic sensibilities shut down, painting and piano-playing waned. So, Schreiber threw herself into academics. So much energy had been focused on her father’s care, and afterwards, a huge void was felt in the family. So, it wasn’t until an exchange trip to Holland during high school when she was about 16 years old where Schreiber’s love for artistic expression began to blossom again into an appreciation for the beauty and expressiveness of storytelling through painting and sculpture.

“I practically lived in the Rijksmuseum and the Kröller-Müller Museum where all the Vincent Van Goghs were at that point,” says Schreiber. “That was a huge influence on me. Art became very personalised.”

Around the same time, Schreiber found her artistic expression rekindled after discovering her father’s cameras and she started taking stills. She and her siblings had recovered the 8mm and 16 mm home movies her dad had photographed when she was young, and they transferred everything to digital. In addition, they found a beautiful black-and-white 8-by-10 photo of their mother and father at a ranch in Arizona wearing full western gear and her dad holding the reins of a horse in one hand and the 8mm camera in the other.

“He really was an amateur cinematographer,” says Schreiber. “I love that my calling in life seemed to be sealed long before I realised or found it.”

In college at the University of Michigan, Schreiber started taking pictures in earnest, using a dark room, learning to develop her own film, and snapping both colour and black-and-white stills. But she was a psychology major and art history minor and thought she was going to become a clinical psychologist following a rigorous honours program. But along the way, she ended up taking a course about perception and remembers well the experiments on altered states of consciousness.

“We looked at a study of movie trailers which showed quick cuts of popcorn in between each trailer,” she says, “and moviegoers were shown to get the subliminal message to buy more popcorn, which they did. I loved it. And I learned a lot about the power of moving imagery. Though, my clinical thesis advisor was not pleased about me embracing the behaviourists school, but I knew deep down that I would not be spending my life as a therapist.”

This was also during the nascent days of the second women’s movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. She began shooting small documentaries and experimental films with women’s groups, and her love for the moving image grew even stronger.

“There wasn’t a film school at my university,” says Schreiber, “but I was able to immerse myself in film history by programming and running The Alley Cinema, part of the Ann Arbor Film Society. We showed mostly all foreign films, the Nouvelle Vague from French filmmakers, Japanese, Swedish, Italian, and Polish films, and also American underground films. And that was my film education, running The Alley Cinema Monday through Thursday nights.”

After graduating from University of Michigan, she followed a boyfriend to New York City who was going back to be with his mother after his father had passed. She knew at that point that clinical psychology was not for her and did not pursue applying to grad schools. But a friend who had moved to NYC the previous year to attend New York University’s film school found a sublet in Greenwich Village and told her about a summer-long course in filmmaking.

“It was me and mostly Vietnam Vets,” says Schreiber of her crash course in filmmaking. “It was wild. But I had a great teacher, Jim Pasternak, who I know to this day and who has inspired so many to pursue the filmmaking path. I was making films all summer with a 16mm Bolex, and when my boyfriend went back to Ann Arbor for law school, I stayed, falling deeper in love with NYC by the day. I answered an ad in the Village Voice and took a job on a movie as a production assistant. That’s when I became devoted to getting into the film industry.”

The film was The Werewolf of Washington, a modestly budgeted political satire shot on 35mm which recreated Washington, D.C. on Long Island. Schreiber was hired to drive a van for $50 a week but ended up helping with props and costumes during pre-production, and eventually becoming an electrician in the tiny lighting department during filming.

“On this first job I felt like I was home,” Schreiber reminisces. “I loved the energy. It suited me. I knew nothing about electricity, and yet I realised there that lighting was such a key to the artistic expression of visual storytelling. I had studied light and shade in endless paintings and photographs over the years and then when creating my own little movies and stills. So, I just threw myself into it.”

Schreiber worked first as an electrician, then best boy, and finally, as a gaffer, and was soon accepted into New York’s NABET Local 15. Gaffer Bobby V. [Vercruse] hired her often for commercials and movies and helped to support her shooting aspirations by loaning her gear from his company, Filmtrucks. There was only one other female gaffer she knew of in NYC, Celeste Gainey, who was the first woman to be admitted into IATSE in 1974. Together, they created Gotham Light and Power, a short-lived gaffing company that joined their respective powers together for a while as they both worked their way up in the industry. And this led her to director/cinematographer Mark Obenhaus and his partner, cinematographer Arthur Albert.

“If I had a mentor,” says Schreiber, “it was probably Mark. We would do these three-week documentaries practically living with different families across the states. I would light the subjects’ whole house up so that, with a flick of a couple of switches, Mark could film 360-degrees. I remember using Polecats floor to ceiling and attaching lights at the top, and then hiding the silver poles with tape the colour of the walls of the home. Mark and Arthur began to loan me their Eclair NPR and were totally supportive of my move from electric to camera.”

Schreiber’s shooting credits date back to 1980 for which she has logged nearly 50 narrative features including Ondi Timoner’s bio-drama Mapplethorpe, Tribeca Film Festival charmer Folk Hero & Funny Guy, and 10 Sundance premieres, including the thriller November for which she took home the Sundance Film Festival cinematography award in 2004. Her television credits include the original The Baby-Sitters Club on Nickelodeon, HBO’s The Comeback, FX’s Better Things, ABC’s Station 19, and Starz’s P-Valley, and dozens of commercials and music videos with the likes of Billy Idol, Billy Joel, Aretha Franklin, and Van Morrison. Her work on 1992’s Chain of Desire earned her an Independent Spirit Award nomination, and she received her first Emmy nomination in 1996 for shooting the stylised documentary, The Celluloid Closet.

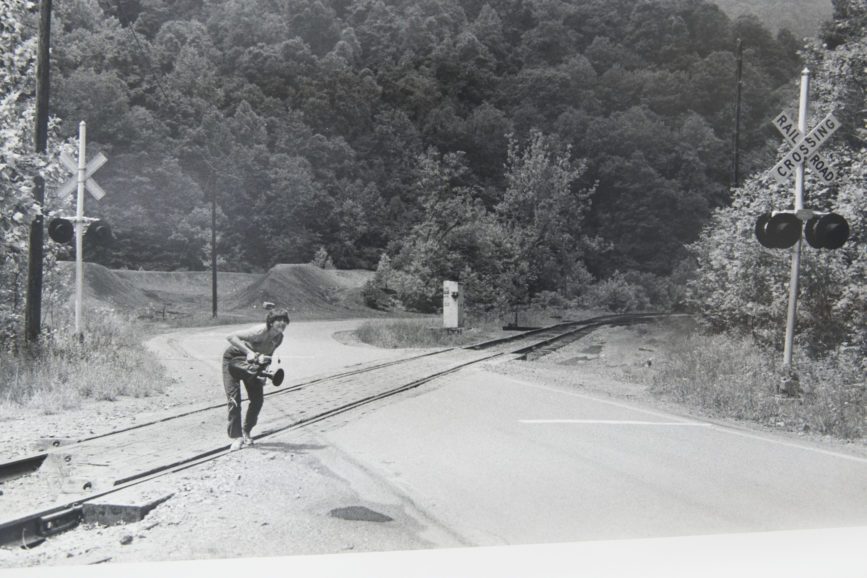

Schreiber also directed and photographed several films, including the documentary, Possum Living. This was early in her shooting career, and since documentaries were where the women were getting hired at the time, she used this film to demonstrate that she could shoot handled. Possum Living was chosen for the prestigious film festival, New Directors/New Films, and even recently was restored by IndieCollect, partially funded Jane Fonda.

In 2017, Schreiber was the first woman to receive the American Society of Cinematographer’s President’s Award after joining the male-dominated club in 1995 as the fourth woman ever to be accepted into the prestigious ranks. But as Schreiber told Variety on the eve of receiving her President’s Award, “If I had paid attention to [sexism] being an issue I would not be where I am today. You can’t focus on obstacles. It would have been ludicrous to have those types of thoughts in my head – self-defeatist really.”

She says now: “I had a calling, and nothing would stop me from pursuing my passion.”

And just as she operated in her early days in NYC, nowadays, Schreiber doesn’t stop to think about the challenges which may arise from being a cinematographer who happens to be a woman who happens to have been around for many decades. She just gets in the truck and drives. Or rather, today, she participates in boot camp workout classes three times a week and a Zumba dance class two times a week. “Some of us are in pretty good shape,” she says, nodding to an aging but still active contingent of cinematographers. “And we don’t want to be thrown away. Unfortunately, experience is not necessarily celebrated, as the industry seems to always be drawn to who’s new and hot.”

“It’s still an uphill battle for all the isms—sexism, ageism, racism—you name it,” continues Schreiber. “There are mandates and quotas now within the studios, and that can get very tricky. You want the best people out there for the job, and the underrepresented people might not even have made it into the room, as it has been hard to get opportunities in the first place. There is still some pushback and resentment toward quotas, but things are changing as the need to ‘hire diverse’ gets embedded into people’s consciousness. Our sets are beginning to better reflect the makeup of society in America.”

Recently, Schreiber shot the Amazon Studios pilot, Hot Pink, a comedy starring Sarah Michelle Gellar and David Arquette, which hired nearly all women to run every head of department: The director, showrunner, line producer, creative producer, production designer, editor and Schreiber’s entire A-camera team were all women. Her B-camera team was diverse, too. As was her P-Valley camera, grip, and electric departments.

“Early in my career,” says Schreiber, “I know that I raised a lot of eyebrows when I would walk on set with an assistant who was a woman or a person of colour. I know how hard it was for me to get work. And I have always been committed to showing how competent these artists and technicians are, and just need an opportunity to prove themselves. It is crucial for each of use to pay it forward to the next generation.”