INVISIBLE IMPACT

Jordan Peele relied on the services of MPC to ensure the VFX was fantastical, yet grounded in realism, to achieve the right tone for his sci-fi horror epic Nope.

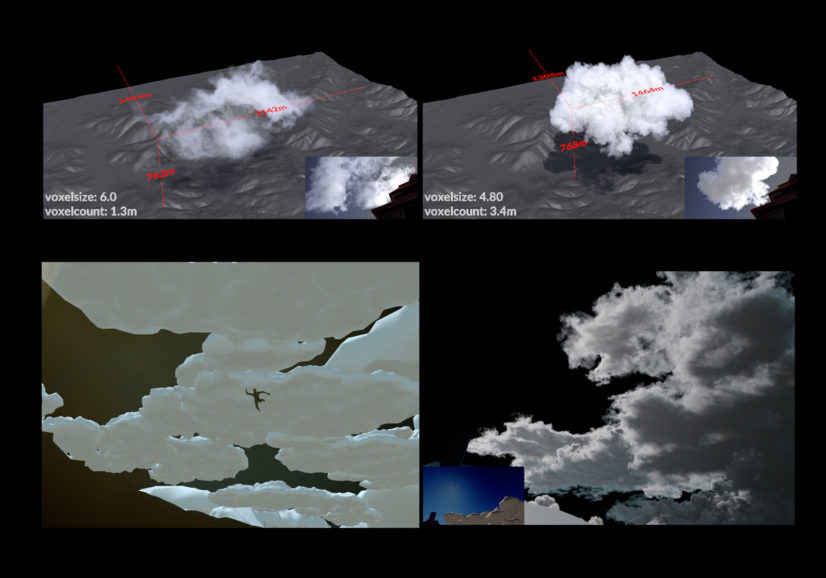

MPC VFX supervisor, Guillaume Rocheron, spoke to British Cinematographer in order to enlighten us on how to break boundaries with VFX, whilst making sure the audience isn’t removed from the reality being presented on screen. For Nope, this involved MPC creating an incredibly in-depth cloudscape system, as well as placing computer generated animals into notoriously difficult semi-transparent environments.

The balance between realism and haunting supernaturalism is achieved to immense effect as the film sees a run-of-the-mill town in California rocked by chilling discoveries.

How particularly important is VFX to horror, where the suspension of disbelief is a cornerstone of the genre?

I think that, as with best suspenseful scenes, the key is to engage your audience to show them something they haven’t seen before, but at the same time, leave enough room for imagination to complete the picture.

VFX is a great tool to achieve this, as long as it is used to propel the story, or the experience of the audience, forward. I don’t think VFX and CG in general impress audiences anymore unless you try to offer a different experience.

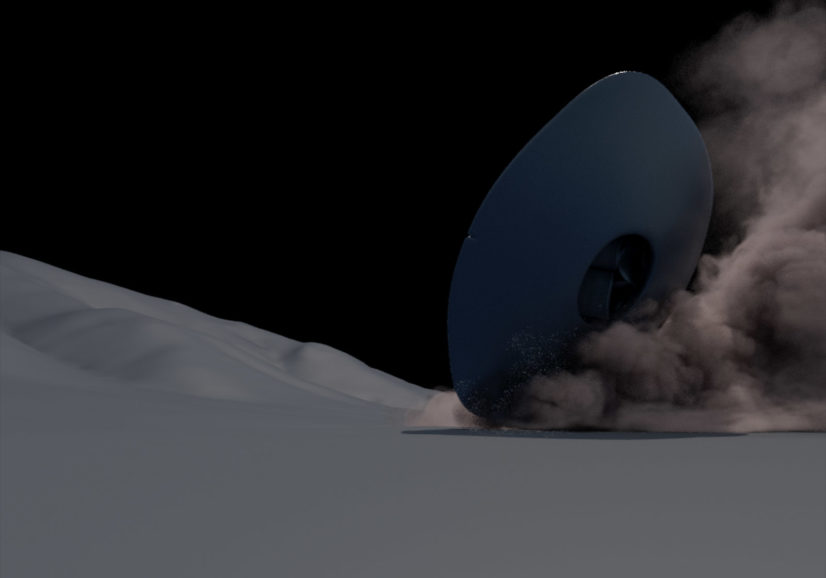

On Nope, Jordan was a big advocate of constantly pushing us to find new ways to suggest things instead of presenting them perfectly. If you look at the Gordy scene, the chimp is CGI, but we went to great lengths to showcase it through a semi-transparent tablecloth. Or with the UFO (nicknamed Jean Jacket), it is always in clouds or through the dust.

This made our work much more complicated; instead of just having to animate a flying saucer in a shot, we had to create and simulate entire cloudscapes around it. I personally think that the more accurate and invisible the VFX is, the more effective the impact of the work is.

Does your approach differentiate from genre to genre?

I don’t really change my approach based on the genre; I think you adapt it to the group of people you are working with. The first step is to understand the director’s vision and find ways to support it as best as possible. It is generally a very collaborative effort between all the departments to put effort into capturing as much as possible in camera, so there is a realistic foundation to build the VFX work upon.

How did you collaborate with cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema FSF NSC ASC when constructing models and sequences?

Hoyte is incredibly collaborative and a great engineer. We previsualised most of the encounters because of the shoot, and Hoyte and Jordan were constantly involved in designing shots and moments with a unified vision.

We also collaborated very closely to create the night scenes of the film. Unlike traditional lit movie nights, we wanted to develop nights as the human eye sees. Our instinct drove us to want to shoot day for night, but we wanted the nights to feel real and immersive. Hoyte designed a camera rig to film each night shot with two cameras aligned and synchronised: an infrared Alexa 65 and a 65mm film camera.

Because we were shooting in the middle of the day, infrared gave us black skies and contrasts akin to how to eye sees at night. But, the infrared is black and white, so we created VFX techniques to colourise the infrared footage using the synchronised 65mm film camera, and we found ways to extract depth and features to model the sky’s and landscape’s visibility realistically.

What existing creative inspirations did you draw from?

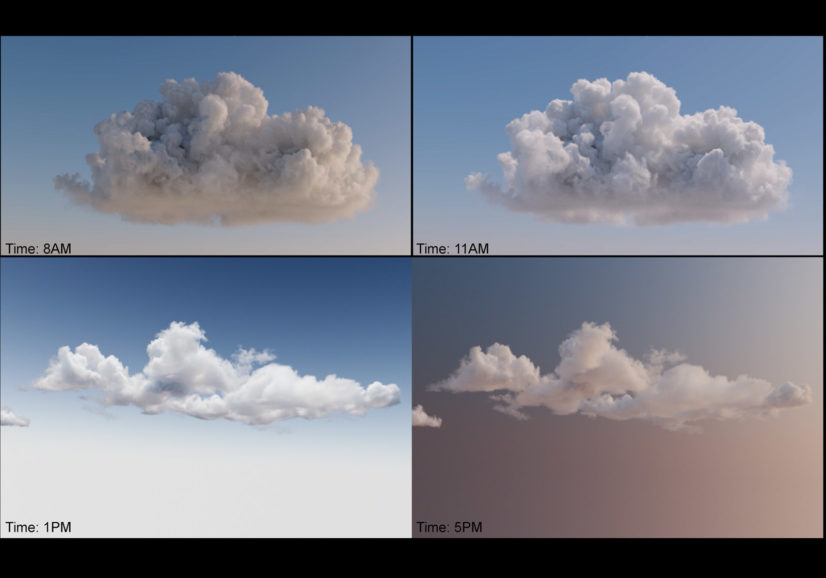

Jordan screened the 1933 King Kong, Jaws, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. They were definitely in our heads when discussing how to bring awe and terror with a certain visual restraint. And we looked a lot at nature for the behaviour of Jean Jacket and Gordy. My team and I spent countless hours looking at clouds to understand how to make them realistic.

Hopefully, it is invisible to the audience, but our computer graphics artists create the skies and clouds throughout the film. It was crucial that the audience would never question the reality of the skies.

What conversations were had surrounding the final design of the UFO? Was this the longest part to design given its importance?

This was the first thing I started to work on and the last we finished, well into the post-production schedule. As Jordan was writing the script, we did designs very early on with concept artist Leandre Lagrange at MPC, and we very quickly settled based on Jean Jacket.

We talked a lot about birds and mysterious sea creatures. An extensive reference was Neon Genesis Evangelion in terms of minimalistic design. We were striving for something unique but very minimalistic and functional. After the initial design pass, we consulted with multiple scientists in different fields to discuss anatomy, biology, and aero dynamism. Professor Daribi at Caltech, an expert in jellyfish propulsion, was instrumental in giving us realistic cues to make Jean Jacket functional and economical in its movement within its environment.

How did Jordan Peele’s artistic vision stand out when designing the VFX?

Everything we did so specific to Jordan’s vision. He is incredibly tuned in to how an audience experiences each scene and each shot. He creates a very collaborative environment between all the heads of the department to help him shape different ideas and creates an honest dialogue. He involved Nicholas Monsour, his editor, and Johnnie Burn, his sound designer, very early in the process.

Sometimes, the sound design would guide some of the visual designs and vice-versa. He is incredible at finding the perspective that will make the VFX more grounded and real within the context of his story.

What was the biggest takeaway you got from Peele’s approach?

I just loved the continuous brainstorming to try to improve our ideas and shots design. He really uses all the tools he has available to service the story and the experience, whether it is visual effects, practical effects, or sound. It is a big collaboration between all of us.

What was the hardest sequence to design?

There were many very specific challenges in each scene, but I would say that the common thread between all of them was the skies and the clouds. MPC spent a year developing a system that could allow us to design realistic cloudscapes that would be utterly modular. You designed a set that could be realistically lit to fit in Hoyte’s photography. That was our basis for all the work on the film and took us a lot of engineering and post-production time.

What was your personal favorite sequence, or detail, you constructed?

The design of Jean Jacket was something really interesting to put together.

I really like how we achieved the night scenes in terms of sequences. I think the combination of infrared and colour footage allowed us to create something the audience had never experienced like this in a movie. Seeing the vastness of the sky at night is incredibly immersive and scary.

What lesson will you take away from the project?

There is never a status quo in my job; you are constantly learning new things which is what makes it so enjoyable, especially collaborating with people like Jordan, Ian, Hoyte, Nicholas and Johnnie.

What can MPC’s work on Nope demonstrate about the future of VFX and storytelling?

Our approach was to make the VFX as invisible as possible, even though this is a science fiction film with a lot of impossible things happening. It was a refreshing approach for a large film, like immersing the audience in something closer to a real experience than a spectacle for the sake of spectacle.