Lighting the way

The cinematographer and director behind a Goya Awards-shortlisted documentary set against a backdrop of Sierra Leone’s energy crisis reveal their filmmaking choices.

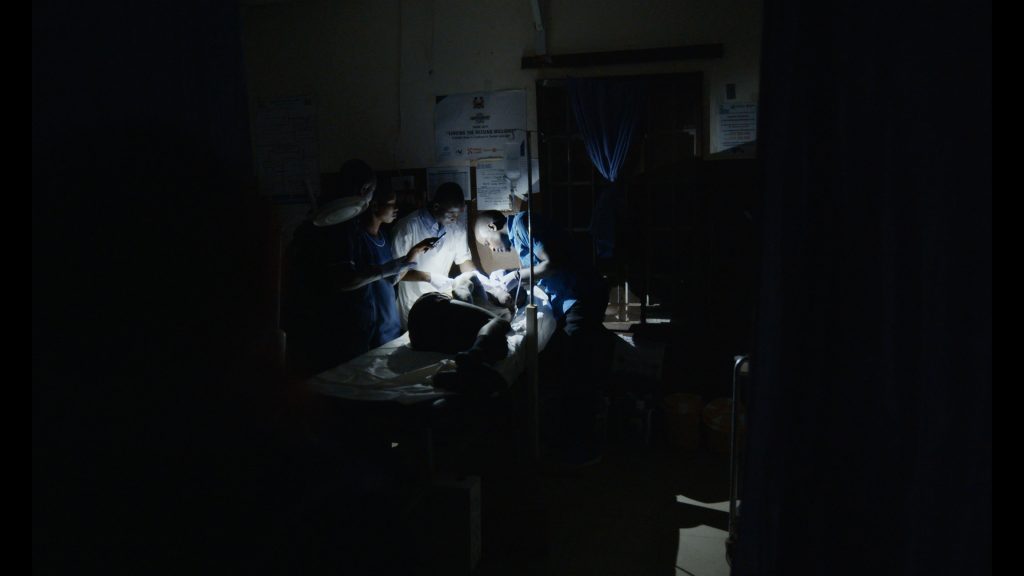

The Road Bad and the Place Dark takes viewers to Sierra Leone, and inside the hospitals of the Koinadugu district, exploring how workers and patients grapple with the challenges of limited electricity. We spoke to director Borja Larrondo and cinematographer Miguel Angel Viñas about capturing the dark reality of life in one of the world’s poorest countries.

British Cinematographer: Could you each introduce yourselves and tell us a bit about your filmmaking journey so far?

Miguel Angel Viñas: I am a Spanish cinematographer who lived in Ireland for 13 years. I started working in the film industry as a camera intern in movies like Guerrilla, (dir. Steven Soderbergh), Broken Embraces (dir. Pedro Almodóvar) and Biutiful (dir. Alejandro González Iñárritu); after several years of being a camera intern I stepped up to become a 2nd assistant camera with the same people I was working with, then I moved to Ireland, where I started shooting short films and became a cinematographer. England is now home and a new and exciting adventure!

When I was a camera intern I used to drive all the cinematographers crazy with questions and thoughts about why they lit scenes the way they lit them or why they moved the camera in a certain way. I remember Prieto, Kamiński, Chivo and the late Dave Devlin being extremely patient and answering questions when they could. I was never interested in the technical side of the explanations, what I wanted to hear and learn was the creative and artistical reasons, and they all were very good at explaining all those things.

As a cinematographer it is really important to know who you are artistically speaking, and to be able to always pull into that direction. For me, filmmaking is about giving a voice to certain people that might not have the power or the resources to do so and highlight societal issues/changes that could transform their lives. On the other hand, character studies are really attractive to me because you can immerse yourself in their psychological world and show it on screen.

Borja Larrondo: I am Borja Larrondo, director of the documentary The Road Bad and the Place Dark. Like Miguel, I started working and falling in love with this industry from the bottom and with the work of great directors. My time at production company Babieka Films in Spain allowed me to be Ridley Scott’s assistant, where I learned about a way of shooting and its link with cinematography when building new worlds, the importance of aesthetics and production design, and the decision-making regarding the technical aspects of the film when incorporating them into the narrative.

From there I continued my training in documentary photography with a Master’s degree at the EFTI International Centre of Photography and Film in Madrid, which ended with a mentorship at the prestigious Magnum Agency and the tutoring of the great British photographer Peter Marlow, where I was captivated by his gift for photojournalistic language.

I am currently studying Social and Cultural Anthropology at the UNED (Spain), seeking to answer new questions and understand our world and society through the power of the image.

BC: How did you meet and what makes your DP-director partnership so successful?

MAV: Coming from a photographic background, Borja and I share a lot of common references and ideas. While he is more “photojournalist”, I am more “tableau” and I believe that the combination of both talents is what makes our relationship very strong.

We also like similar types of cinema (Eastern European, social documentaries, etc.) and we both work by setting a series of rules to our projects. Sometimes those rules are very loose, like “Let’s move around with the camera to find something that we like”, and some other times they are very thorough: “We are not going to show the windows in the close-ups.” Those rules allow us to create a camera/lighting language that is usually quite artistic but grounded in the reality of the stories we decide to make.

Most of the time we shoot with one or two lenses (21mm and 29mm, or 25mm and 35mm). We don’t like cutting the actions to switch lenses and shoot a close-up because we aim to document what is happening in any given scene. That might lead to moments where we don’t know what the actors are going to do because they are improvising, so cutting is not an option! I’d rather move closer than break the momentum.

Our relationship is like that of siblings, sometimes we are happy together, sometimes we argue together but the most important thing is that we know all that, we like working with each other. [Even more importantly] we are really good friends!

We met through a common friend, Chema Sayago, who is the producer of Lobo Kane, a production company in Spain. Chema and Borja were awarded a project for Médicos Del Mundo (Doctors of the World) in Spain in 2018 and, somehow, Chema thought that I could be a great fit for it. He was right!

BL: As Miguel says, I think we fit together so well and became great friends because of our joint passion: film and photography as life. A way to express ourselves, to make art, to understand, even to dance. That which makes us vibrate. Hence the rules or establishing a dogma for each project. Really, in this sense I think we are very influenced by direct cinema and its opposite, the cinéma verité, and with it the tension that is established between the two when filming. The aesthetics of European cinema, and the freedom of independent American cinema in directing actors and letting go like John Cassavetes.

I think there is always some magic in this. That you can always learn something new from each other’s vision. Something to discover. We talk about friendship, passion and respect as people and professionals.

BC: Why did you decide on Sierra Leone’s unstable power situation as the subject for your documentary?

BL: We are facing an undeclared crisis situation. A crisis of energy dependency that is affecting more and more people around the world every day.

The lack of a stable electricity supply is something that unfortunately occurs in more places than we can imagine and, in the not-so-distant future, along with access to other basic resources, it will be the reason that displaces a large portion of the population towards marginalisation and regression in the face of technological development and prosperity for others.

In an initial search, we considered other countries in the African continent and even areas in Spain and the United Kingdom. However, the chosen location for this first documentary had to have a series of ingredients that would make it unique: “Not too far, not too close.”

It needed to function as a cinematic setting, visually interesting for the camera. We wanted to build an appearance, a character that would captivate the viewer from the very beginning.

[It needed to] be within earshot of an ethnocentric society. The place should be known ubiquitously: Sierra Leone’s civil war and the Ebola outbreak had placed it on the map of Africa. However, its issues had not been explored beyond the latest episode.

Its development, as a country, doesn’t fit into a misguided idea of the Third World that is not really such – not too isolated, distant, or underdeveloped for us to care. They and we are connected in global terms. Their hospital facilities should remind us of those we attend with our families, with our children.

Therefore, the story had to work on both a local and global level. It had to be extrapolatable to other places and hence able to connect with them. We aimed to create a cinematic drama, a narrative dystopia.

BC: When did you shoot the documentary and how long did filming last?

BL: The documentary was filmed in the days leading up to the global COVID-19 lockdown. In fact, during the journey, we were beginning to realize what was coming our way, and the alarming situation they would face due to the lack of resources and medical equipment. We also became aware of the Sierra Leonean people’s resilience, their strong mentality, and their ability to come together to overcome horrors like a civil war and Ebola, and to learn from their experiences.

When we returned to Europe, we found ourselves with many hours of footage depicting the hospital shifts and time to reflect on our experiences.

The journey lasted for 30 days, and the filming took up 10 of those days.

MAV: In a way, the COVID-19 lockdown was extremely beneficial for us as we had time to knock on some doors and say: “We made this documentary, we would like to work with you but we don’t have a budget, we have a lot of time now though, would you do it?”

Everybody was keen on jumping on the project and work on it when they could. We would have not been able to have the collaborators we had if we had to deliver the project when we initially wanted to do so.

Most of the time spent during our shooting days was at night in the different hospitals, waiting for something to happen.

BC: Take us back to prep – what kind of research did you do, and what creative references did you exchange regarding the look of the documentary?

MAV: I remember the day that Borja rang and said: “What would you say if I told you that we are going to shoot a documentary at night in a place with no lights or electricity at all.” I said: “I love it! Sounds like a great challenge!”

From that initial conversation to the moment we started filming we spent about four or five months talking to each other about the core ideas of the documentary.

We decided earlier on that we wanted to embrace the darkness of the spaces while being able to show depth in the shadows. Another key point was to be honest and truthful to the places and people we were going to be documenting, we wanted to be as invisible as possible. Having an observational style was paramount to this approach since we did not want to interfere with what was happening around us.

Regarding the camera language, we shared several references like Children of Men, The Hurt Locker, Rosetta and 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days. Those movies incorporate a camera that is self-aware and, sometimes, wanders around to show us the world their characters live in or focuses on something else that is happening within the realm of the movie. All of them have a very observational and non-intrusive camera; they are there as spectators, exactly like you, there are no flourishes and the tension is created by the things that are happening around.

As for the lighting language, we wanted to steer away from the idea of the documentary being shot in Sierra Leone and make it a bit closer to us. On top of that, darkness had to be treated as one of the main characters, one which caught us, grabbed us, absorbed us, our eye had to learn to see inside it.

We knew that we were going to encounter situations where there was no way of getting an image recorded because there was no light at all. I looked at other projects that dealt with similar situations, like The 33, and started thinking about using the tools that the people who were dealing with the lack of electricity used, such as mobile phones, battery-powered headlights and battery-powered camping lights as our lighting tools. Once we embraced that that was the world we were going to explore, the rest was being open to what could happen and use any available light that might make sense in the story.

Borja and I talked a lot about the look of early documentaries and, of course, how the image having a lot of imperfections and grain gave a sense of reality and “being there”, experiencing what the characters where going through. We wanted to translate that feeling to our documentary, even though we were going to have to use a super-new, modern digital camera.

BL: For four-to-five months prior to filming, we identified various countries and cities where we would encounter the same energy problem: a lack of electricity supply and how it could affect society both physically and psychologically, as well as hinder a nation’s development.

This became possible through collaboration with the NGO Médicos del Mundo. Through them, we not only gained more insight into the issue and the daily experiences of those living through it, but the initial idea for the documentary was built around this: personal stories, real stories. We wanted to remain true to journalistic integrity and objectively portray what we were going to encounter.

However, at the time of travelling, everything was yet to be done: establishing contacts, gaining access, and dealing with bureaucracy involving authorities and hospitals. Indeed, prior scouting was crucial in this preparation.

The documentary needed to incorporate the best elements of the documentary genre while also drawing from narrative and visual lessons learned from fiction, in order to make it appealing to an audience that might be somewhat saturated and disconnected from African topics.

We aimed to move away from the stereotypical and exotic idea of Africa – something that would sound “too far away”. Instead, we wanted to create a dystopian, almost apocalyptic story that was socially relatable in terms of the themes and the subjects to be interviewed, yet distant due to the unimaginable nature of the situation.

Our literary and cinematic references were: Ebola. Como suena África (book); Ante el dolor de los demás. Cómo fotografiarlos. Respeto. (book); Children of Men (film) District 13 (film); and The Hurt Locker (film).

Once the language was defined, the rest involved being receptive to what we would encounter, continuously questioning ourselves, and following our instincts.

BC: Which camera and lenses did you choose and why? Which rental house did these come from?

BL: Any filming equipment always ends up being cumbersome and intrusive. And typically, a documentarian or a photojournalist is always the outsider in the field – someone who doesn’t belong to the reality being shown and told. The first conversation we had was about how to avoid building that barrier that could undermine the project. We didn’t want to lose the sensitivity, humanity, and respect for what we were going to portray. We wanted to be invisible.

On the other hand, we needed to find a way to be as self-sufficient as possible. Recording equipment that consumed power like a lighter (both batteries and memory cards for downloading). Something compact and easy to handle. It had to be capable of seeing in the darkest night we were about to face, in contrast to the situations we would encounter during the day.

Our suppliers were Welab and MadCrew in Spain.

MAV: When we started preparing The Road Bad and the Place Dark, one of the main challenges was exactly what camera and lenses we were going to use and why.

We had to use something that was able to record an image in cases of a total absence of light, graciously deal with the sun in Sierra Leone yet being light enough that we could travel and move fast with it.

Since we were aiming to go back to the roots of documentary, we were very keen on shooting on Super 16. Thanks to our producer, Chema, who kindly explained all the logistical reasons as to why we should consider other options we quickly moved from that idea and began exploring other tools.

At the time I was very impressed by the Sony Venice, having used it in a couple of commercials pushing its sensor to the highest settings I knew that it could handle really extreme situations lighting wise, it had all the needed Internal ND filters and was compact enough to move around with it. But our budget couldn’t afford a Sony Venice and the Sony FX9 was just out.

I met with the Sony representatives in the camera rental house we were going to rent the equipment from, Welab, and they gave me a quick tour of the capabilities of the camera. I was super impressed by the fact that I could use a 4000 ISO as a baseline and then go higher and open up the shutter to get more light in and start creating aberrations in the image and get more noise.

In theory, the Sony FX9 ticked all the boxes, so we set up 1/2 day of tests in Welab where we shot a model through different lighting setups, different ISOs, underexposing, overexposing, etc. Once we finished the tests we discovered that we liked the look and noise of the camera at 10,000 ASA or 10,000 ASA + shutter off and underexposed 1 1/2 or 2 stops. We asked one of our DIT friends, Montse Motril, to make a LUT based on those sets and off we went to Sierra Leone!

It was the right camera for how we wanted to film the project and we shot everything at T2, 10,000 ASA and 1 1/2 or 2 stops underexposed in camera so we could get noise in our image and be closer to our social realism references.

As for lenses, I mainly shoot with either one or two lenses so that really fit the box of “being light”. I looked at the Super Speed lenses, which are one of my favourite lenses of all times, however, I wanted to be able to have a more contemporary look, as well as more depth and the Super Speed didn’t provide that.

The Supreme Primes and the Leica Summilux were available in the rental house and as I had worked with both sets before and the Supreme Primes were smaller, we picked two Supreme Prime lenses, the 21mm and the 29mm, together with a doubler (which we used once). I love the Supreme Primes, they have a wonderful timeless look and they render faces beautifully.

We had several thoughts about what focal lenses to use. Initially we wanted to have a 21mm and a 35mm, using the 21mm for the wide shots and using the 35mm with the medium shots and close ups to present the characters in a more honourable manner. Through the months of prep we started to think about how a 21mm and a 35mm were going to fit together seamlessly, and because we don’t really like swapping lenses we thought that the 35mm could be a bit restrictive if we did not have space to move. When we shot the tests we used a 29mm instead of a 35mm and we fell in love with how it portrayed faces and how it opened up the world. As you can imagine, we shot most of The Road Bad and the Place Dark with the 29mm.

On top of the lenses, I always used a Glimmerglass 1 + Black Diffusion FX1, which are my standard filters.

Our first assistant camera, Ismael Blanco, was able to fit the camera, the accessories and the lenses in two simple backpacks while travelling to Sierra Leone. Once we got there, the camera and the accessories were always ready to go and we had just one backpack with us for the media, batteries, hard drives and the other lens.

BC: How easy was it to get access, for example to the hospitals?

BL: It was a matter of time and trust. During the initial shifts in the hospitals, we entered as “civilians”, armed only with a notebook and a pen. Gradually, the mutual interest in what was happening in the hospital and our presence there grew. After a few days, we introduced the camera into these shifts, but we only uncovered the lens to conduct various lighting tests. On the 10th day, we shot our first frame.

BC: Can you tell us about your approach to framing and composition? How did your choice of aspect ratio play into this?

MAV: My favourite aspect ratio is 1.33:1, I believe that there is harmony in how it serves as a portraiture aspect ratio while psychologically driving the attention of the viewer into the artist’s performance. You are focused on the gestures, the face, the body language and everything else just disappears. There is no space left in the frame.

On top of that, if I want to use negative space I can do so really well and play with composition by driving the attention towards the centre of the image or one of the corners, etc.

I happen to like taller aspect ratios the most because you can see more of the performance and you can be closer to the artist.

That said, while exploring options for The Road Bad & The Place Dark we realised that 1.33:1 was going to be a bit restrictive because we were not going to be able to show much of the world around the characters when we were up close with them.

We eventually landed on 1.66:1, which let us have the same height and be close to the people we were going to interview while allowing us to see more of the world around them. Coincidentally, 1.66:1 is the aspect ratio of Super 16, which was the documentary workhorse back in the day and a feeling that we were keen on bringing back, those documentaries that were more about finding things on the spot and constructing a narrative on the go than having everything lined up.

Believe it or not we spent many hours talking about the aspect ratio and how the documentary would benefit from one or the other.

BL: In terms of style and language, our intention was always to revalue the genre. This is why we chose a classic aspect ratio, reminiscent of the early film recording formats. To apply that direct cinema we were talking about before, where the documentary genre and the camera would be the maximum expression of the conception of cinema as a “window to the world”.

Choosing an aspect ratio that led us to talk about Super 16 also connected us to the next aspect. The grainy image, a “dirtier” image that seemed to bring a plus of realism to those early documentaries. Also the use of synchronous sound appealing to spontaneity, to chance, to the lack of control of the situation. So, we had to force the ASA and mistreat the sensor so that the viewer could be there with us.

The framing, composition, and behaviour of the camera were meant to convey the sense of being present in the moment. It was akin to an outsider’s gaze driven by the intention to discover, reminiscent of the early photojournalists of magazines like LIFE. Through their experienced portrayal, they brought forth a new reality, connecting it with the rest of the world. Hence, the camera movements and its freedom to navigate through different spaces, whether it be the city or a hospital.

BC: Were there any new tools or techniques you used on this production?

MAV: Not new tools or techniques per se as pushing ASAs is something that we have done since the first steps of photography. I like pushing digital camera sensors until I break them. I believe that once you start making the camera misbehave, the images coming from it suddenly become quite interesting.

The noise, the texture, the lack of perfection, the strange artifacts, those are the things that I am attracted to and having the ability to decide when you want to push/pull a camera’s ASA for artistical reasons and see it live is extremely useful. We can do that nowadays because we have digital cameras that have a wide range of ASAs and while one cinematographer might prefer to shoot everything at 400ASA, another would prefer to shoot everything at 10.000ASA to get a different result or use more filters in front/behind a lens.

Being able to have a light that was battery powered, lasted for a really long time and emitted a big quantity of light was groundbreaking, we wouldn’t have been able to make this project as it is without the Astera tubes, they were a game changer.

Having a defined and clear understanding of what you want to achieve and how to use our tools to accomplish that is what makes the art of filmmaking a marvellous one.

BL: Rather than relying on new tools, our aim was to uphold and highlight classic techniques. We wanted to take the best from various genres to engage the audience in the storytelling. We needed to transport them to the nights of Kabala and make them feel the terror of darkness.

Speaking of the references mentioned earlier, perhaps the pacing of the film Children of Men was one of the aspects that influenced us the most – how tension gradually seeps into the audience as spectators.

BC: Tell us about how you lit The Road Bad & The Place Dark?

MAV: I wanted The Road Bad & The Place Dark to feel as if there was no cinematographer behind it. Just a person who happened to be there and pressed record while things unfolded.

As with the camera equipment, we had to use lighting kit that was portable, light and didn’t use much power. My longtime friend and gaffer, Sergio Fuidia and I had many conversations about what we could use but more importantly about the things that we could not use because of the limitations of the project.

To me, it is important to give space on a set to the artists and the director. Not having to retouch the lighting from wide shots to close ups is my preference and if I can, I light for 270 degrees, usually with windows behind and in front of the characters so that I can modify the contrast as needed. That process always leads to me lighting spaces rather than actors and blocking the actions in a way that we maximise the already existing natural/available light or the one that I am going to create.

Most of the time I light from outside and create contrast by using frames with black fabric or nets near the characters.

Let’s add the fact that we were going to be in a place with no electrical power and that makes things extremely interesting since the units that we were going to use were going to be always the ones that were the brightest in the whole town.

Coming back to the idea of being able to move quickly we prepared two backpacks, one with two Aladdin lights (1×1 and 2×1), some batteries, clamps and cables and another one with two Astera tubes. We also used a light that Sergio brought with him, an AtomCube, which is a light the size of an iPhone but super powerful and with a lot of effects. It is like a mini SkyPanel that you can control through your phone! When we used our “film” lights (mainly in our interviews) we used them to light different spaces from outside and convey the idea that some street lights were around the area and were lighting the interiors of the rooms.

However, most of the times we used the lights that are in the frame to light the spaces or the actions. In fact, Sergio and Diego Sanchez, our production assistant/photographer, went to the different street markets in Sierra Leone to buy several portable camping lights/headlights/flashlights that we could give to the doctors so they could use them as they normally would or that we could place somewhere in our frame. We were able to use those lights as our key lights because we were shooting at a really high ASA.

Ethically, we couldn’t brighten a scene as we envisioned and then leave midway through a surgery, leaving them without light. That wouldn’t make any sense at all!

BL: Our idea was to try to be invisible. To create an accurate snapshot of the situation and way of life. And this set the first principle of the project: no interference.

We had to be grounded in the reality we found (the energy situation), a challenge both for life and the project, and turn it into our greatest asset – the cinematography. This meant being prepared for everything. Working with the existing lighting conditions in the hospital and those the doctors worked with.

Therefore, we decided that we would never artificially light the scenes, only the exteriors. Any sources of light (flashlights) that appeared had to come from local markets. That would serve as the foundation for the interviews and action sequences.

BC: What was the trickiest location to light?

MAV: Emotionally speaking, the most difficult location to light for me was the interview with the mother and the baby.

The lighting itself was as simple as it gets, a 2 x 1 Aladdin outside the window.

However, thanks to not having to rely on any lights in the interior and being free to roam around the room and go from wide to close at any time (as opposed as traditional filmmaking where you usually cut and light the close-ups, etc.) we were able to hear her story without any interference, she started to talk, we just listened and it was heartbreaking.

BL: Perhaps the opening scene. We weren’t fully aware until we saw it there, standing still. A woman’s figure in that hospital room – solemn and impactful. So much to convey in such a confined space. A flashlight guiding us, revealing the horror of a burned body. The pain of a lifelong scar. The most faithful portrayal of the situation we were about to confront.

BC: Who did the grade and what was their brief?

MAV: Jenny Montgomery, from Company 3, was the colour grading artist who worked with us on The Road Bad & The Place Dark.

Not having worked with her before, we created a PDF document with our images and I explained in detail the feeling we wanted to achieve together with some reference images. The base of the brief was to make it look like it was just around the corner of everybody’s house.

When she came back with the grading I was really nervous before watching it; I am usually in the room when the colour grading happens and I don’t like things changing much! After I finished watching it I could not believe what she had done, not only had she elevated the cinematography at a different level but also added an extra layer to the story, we were able to see the complexity of the emotions in people’s faces. The spaces had depth in the shadows! I called Borja and told him: “I am not going to tell you anything else other than WATCH IT NOW!”

Jenny is absolutely wonderful.

BL: Just like in the editing process, we sought a female perspective for this crucial role. Frankly, Jenny’s contribution was instrumental in the quality of the documentary. Alongside the direction of photography, she managed to give depth and dimensionality to that room. Through her work, we were able to transport ourselves back to Sierra Leone and see in the darkness.

In terms of instructions, the main goal was to steer clear of the typical warm and exotic images associated with the African continent. We wanted Africa to appear as a part of London, in terms of visual representation.

BC: What are you most proud of from your work on The Road Bad & The Place Dark?

MAV: I love the fact that thanks to our documentary and the people involved in it, we were able to highlight a problem that was happening in Sierra Leone, raise awareness and find funding to successfully solve the issue. Telling a real human story through a lens and be part of the actual change is a wonderful feeling.

BL: In addition, we are incredibly proud of the final outcome of The Road Bad and the Place Dark. The staging, cinematography, and sound design make it a powerful project that emphasises cinematic production values. We were a small but highly talented team, with each department led by skilled individuals. Perhaps our greatest source of pride has been working together to pursue a shared goal relentlessly until achieving it. It has been a pleasure to have these individuals as part of the project.

BC: Is there anything you’d do differently?

MAV: I would have loved to be able to spend more time discovering and recording the different paths that kept opening up through the different conversations that we had with people. Some of the different avenues were really interesting and worth exploring in a different documentary.

BL: More days, more footage, more topics.

BC: What are you working on next?

MAV: I just started working as the cinematographer on an AAA video game that is using Avatar‘s technology to seamlessly integrate both mediums, videogames and movies. We work in a very much “film set” style. We block our scenes with our actors in physical sets that represent our videogame sets. When we have the shots that we want, we “transfer” them to our “video game” sets and polish them (lighting-wise). With a budget that is nearly as much as that of a Marvel movie and having the whole control of the world, it is a cinematographer’s dream!

BL: Our vision is for The Road Bad and the Place Dark to become the first episode of a series of documentaries focused on the same theme – poverty or energy scarcity. We are currently in the editing process of a second documentary set in Spain, specifically in the Cañada Real area of Madrid. This territory spans 16 kilometres and its population has been deprived of energy supply for years, resulting in profound psychological health consequences.

Our goal is to connect this issue on a global level – different locations, continents, and realities, all tied together by a common denominator: energy.

I sincerely believe that these last nominations such as the Goya or the BAFTA could give the project the fuel it needs.

BC: Are there any team members not yet mentioned that you’d like to highlight?

BL: As I said before, we have been a small family of professionals who have been behind and have given life to this project. Those who went to Sierra Leone and those who joined us on our return. The editing, the sound design, the colour grading… To make a project at the height of the story we tell. Everything passes through the hands of each one of them, and begins with gratitude to the people of Sierra Leone who have made it possible.

MAV: Everybody who was involved in the project has been very kind with their time and their knowledge. Our producers, Ramon Corominas, Chema Sayago and Eva de Lera were very understanding when we told them what we intended to accomplish. Nerea Muguerza, our editor, was able to create a compelling story out of our hours and hours of footage with the limited time that she had.