BITTERSWEET SYMPHONY

A passion project many years in the making, Maestro immerses the audience in the life of composer-conductor Leonard Bernstein and his complex yet deep love for wife Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein. Following their success with another musically focused film – A Star is Born – director, co-writer and star, Bradley Cooper reunites with Matthew Libatique ASC LPS to lens the extraordinary life story.

Much like the soaring symphonies Leonard Bernstein is renowned for composing and conducting, the themes in Maestro are instruments working in harmony to tell the captivating story of a compelling character and the complexities of an unconventional marriage. Both a celebration of a master of his craft and a poignant portrayal of a love that lasted a lifetime, biopic Maestro chronicles the life and relationship of the composer-conductor (played by Bradley Cooper) and his wife, actress, artist, and activist, Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein (Carey Mulligan). The film charts their instant emotional connection and enduring love that enjoyed highs as well as facing challenges.

A movie of two narrative worlds, the story begins in the monochrome realm – capturing the start of their relationship, their careers and the family they raised – before colour is introduced as the focus shifts to their later years when cracks begin to appear in their marriage as it is tested by Leonard’s affairs with men.

Cooper was destined to make a movie about Leonard Bernstein, having had an urge to conduct since childhood. He was handed the script by Steven Spielberg, who originally set out to direct the film before he saw A Star is Born – directed by and starring Cooper – and realised he would be the perfect fit to direct. Once Cooper had decided to take on that role and co-write the script with Josh Singer, with Spielberg serving as one of the film’s producers, he immersed himself in detailed research into Leonard and his family’s lives.

He explored Leonard’s vast back catalogue along with photos, video footage and interviews, documentaries and books including Jamie Bernstein’s Famous Father Girl. Leonard’s three children – Jamie, Alexander, and Nina – were also involved during the writing stages of the script. Cooper discovered “the most interesting and relatable aspect” was the marriage between Leonard and Felicia. “It was an unorthodox, genuine love that I found endlessly intriguing,” he says. Alongside the love story was another key narrative strand – “the music, the great works both composed and conducted by Bernstein that serve as the score within the film.”

Shortly after Matthew Libatique ASC LPS (The Whale, Black Swan) shot his first project starring and directed by Cooper, the Oscar-nominated A Star is Born (2018), Cooper was eager to talk to him about his next production, pitching the story of the film about Leonard Bernstein’s life before it was a screenplay.

“At that moment, I had no idea about the extent of his fascination with the man, the art of conducting and classical music, but I then learnt he was obsessed with getting this role and film right and paying respect to this extraordinary life,” says Libatique.

The filmmakers tried to portray the story as honestly as possible “without getting too cluttered with technique” and being “more presentational” with Leonard. “He was unapologetically himself. In the beginning when he and Felicia watch the ballet On the Town, he says ‘I want a lot of things’, and that is true. He is a man who struggled bridging the gap between his public life and personal life,” says Libatique.

“He loves to compose music, but it’s lonely, so he likes to perform too because he’s surrounded by people. And that’s how he lived his personal life – he loved to be at parties, he loved people but he also loved to retreat back to his family and spend time with his kids and Felicia, so he was kind of living two lives. The thrust of the film is not only the strength of the relationship, but that this man was living a life that was unheard of at the time.”

Musical master

With music at the core of A Star is Born, Cooper worked extensively on his voice. When prepping for Maestro he immersed himself once again, being as prepared as possible as a performer so he could focus on directing. Libatique also embarked on a fascinating five years of research and testing, shooting proof of concept along the way.

Working with a director who is also one of the film’s protagonists was a familiar and enjoyable experience for Libatique, having done so for A Star is Born. “I don’t find it odd. Everything is centred around the camera still and there’s less peripheral noise,” he says. “It’s about the inner circle of who’s making it. Bradley likes it that way and I embrace working with a small group of people too. Some come in and out of that circle, but generally it’s the same 12 people.”

Locations were scouted and sets were built during a process which saw Cooper and key crew members visit some locations that had played a starring role in Leonard’s life including Carnegie Hall, Ely Cathedral in Cambridgeshire, Tanglewood, the Bernstein’s home in Connecticut, where several key sequences were captured, and their apartment – the Dakota – to later recreate it.

Cooper was keen to test makeup early so his transformation into Leonard was authentic. Prosthetic makeup designer Kazu Hiro (Darkest Hour, Bombshell) designed five stages of prosthetics, representing different phases of Leonard’s life. “It was important for us to be fluid and flexible,” says Hiro. “We continued to improve every look, even during filming.”

Shot on 35mm film, Maestro traverses black-and-white and colour as the story moves from the ’40s to the ‘80s. “I think Bradley’s first instinct was black-and-white and over the course of years we debated whether to go to colour at all and whether to shoot anamorphic or spherical,” says Libatique. “We even debated shooting some digital at the end of the film and were discussing aspect ratios changing from 2.40 to 1.33 until we realised that might be a step too far. Bradley wanted to be more of a purist by shooting on film.”

The filmmakers landed on “something simpler” by beginning with black-and-white and a 1.33 aspect ratio before transitioning to colour and remaining in the same aspect ratio for the most part. At the end, for scenes taking place in 1989, and when Felicia becomes sick, the film moves into what Cooper refers to as a “more relatable” 1.85.

This framing is appropriate, says Libatique, because the 1.33 frame “allows Leonard and Felicia to share the frame and exist in an embrace of their new world together.” Their relationship is set up in this way from when they first meet at a party. “In the next scene, they’re in a tight two shot profile, with the party behind them. It’s a 1.33 frame where half their heads are actually out of the frame,” he adds. “That tight frame exists again when she takes him to the theatre and they kiss. Later, when they fight, again, they’re both in the frame, but it’s much wider. And then towards the end Leonard is by himself in a 1.85 frame with all this negative space on either side.”

An extraordinary life

Libatique resisted looking at old black-and-white cinema to avoid “falling into the traps of how filmmakers back then had to do things based on technology. It’s not an old movie we were trying to recreate – we were recreating the realism of an extraordinary life.” Family photographs in John Gruen’s book The Private World of Leonard Bernstein provided inspiration along with the naturalism of photographer Elliott Erwitt’s candid black-and-white work.

Three primary stocks were selected: Eastman Double-X 5222 for the black-and-white scenes of Leonard and Felicia’s early years, Kodak VISION3 500T for the interior colour scenes, with 200T for colour exteriors.

When capturing colour segments of the story, the cinematographer strived for a nostalgic look. “I didn’t think I could achieve a Kodachrome feel, although that would have been fantastic,” he says. “I opted to shoot Kodak VISION3 200T – a 200 ISO stock I’ve had amazing results with before by underexposing and rating it at 400 or 320 and then printing up which I repeated on Maestro.”

Shooting on 35mm 4-perf film – with all processing taking place at FotoKem – was the only route for Libatique who believes film stock has the power to transport you. “Having tested every format, this was something Bradley and I 100% agreed on,” he says. “The proof of concept is this quilt of formats. Every time we looked at the black-and-white film, it was magic. Shooting on film is special; there’s something already there – you’re 80% into the final look. Whereas digital was just an image that had to continue to be worked on, like a lump of clay.”

As the black-and-white stock was thin, the filmmakers needed to ensure the pressure plates in the front of the camera had no reflectivity. “This discovery was made by Mark Van Horne at FotoKem who processed our negatives,” says Libatique. “From working on Oppenheimer he knew you need to go with black pressure plates which Panavision outfitted us with.”

After filming, the print was run through the DI process with Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company 3. “Here, the 35mm film was meticulously scanned into a digital format,” says Libatique. “This allowed for precise colour grading, refining the film’s look and feel, and seamlessly integrating our visual effects. Every frame was optimised to ensure clarity and consistency. Sound was then synced, and the film was prepared for both 35mm projection and digital formats.”

When deciding which lenses to pair with the two Panavision Panaflex Millennium XL2s – and an additional Panaflex Millennium XL for Steadicam shots – capturing the lyrical life story, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza influenced the selection of Panavision’s wide variety of glass which resulted in the use of vintage prime lenses, PVintage.

“Bradley was taken by some of that film’s lens choices, and through testing at Panavision with Guy McVicker we felt the PVintage was a hybrid set that offered a detuned quality but also the reliability we wanted,” he says. “They were peppered in different focal lengths for this film. As I wanted a 27mm, but there isn’t one in the set, we went with a 27mm Primo.”

The 29mm T1.2 PVintage Ultra Speed lens was a favourite, followed by the 35mm T1.6 PVintage. Other frequently used lenses included the 24mm T1.2 PVintage, 50mm T1.0 PVintage, and 21mm T1.9 Primo. For specific visual requirements, the 75mm T1.6 PVintage, 100mm T1.6 PVintage, and the 40mm T1.9 Primo Special Optics and 40mm T2 Normal Speed were utilised.

The 27mm T1.9 Primo and 65mm T1.8 Primo Special Optics were used more sparingly, as were the 135mm T2 Zeiss Super Speed. He worked with rehoused Zeiss Super Speed due to their flaring effects, with the 25mm and 35mm being well suited to powerful sequences when Leonard is conducting on stage at Carnegie Hall.

A variety of ND filters were used when needed, as well as polarisers and colour correction filters including the 85 series orange-tinted filters which were primarily used to balance the colour temperature of the film when shooting in daylight.

Lighting up the screen

When Libatique and gaffer John Velez first began testing they lit in the way they would in the current day with LED fixtures such as ARRI SkyPanel S360s. But when then realised they needed more light they went “back to big tungsten fixtures, 5Ks, 10Ks, 20Ks and put it through diffusion, bounced less, and went direct a little more, trying to get the black-and-white to really sing,” explains Libatique.

While shooting the black-and-white sequences and working with Mark Van Horn at FotoKem, Libatique realised his timing lights were often too low because he “played things a little out of shadows”. The solution was exposing more for the shadows and rating the stock at 100 and 120 ISO despite the box rating of 200/160 ISO. “As we tested black-and-white, we realised these new ways wouldn’t work, and it required so much light we’d have to go back to using bigger sources and forcing reflectivity of the face a little, with a little harder light rather than the softness you need in digital.”

When shooting colour sequences, he reverted back to more LED sources such as ARRI SkyPanel S60, S360, Hudson Spiders, and LiteGear LitePanel. Libatique also enjoyed working with the experienced team at FotoKem because “you get timing lights back and as a cinematographer it’s comforting to know that your exposure’s in the right place.”

Libatique also praises Cinelab for their work on the processing and 4K scanning of a portion of the film he consider to be “some of the most important footage” – a powerful moment which sees Leonard in a tour-de-force performance conducting Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” in Cambridgeshire’s Ely Cathedral.

“I had a tremendous time in the UK shooting that sequence and working with incredible crew including gaffer Perry Evans, key grip Darren “Dutch” Holland, and B cam 1st AC Ollie Tellett. “It was daunting to walk into the Ely Cathedral days before shooting and coming up with a plan to light the scene. I relied on the experience of the team to help get us to what’s on the screen.”

Shooting at Carnegie Hall was also challenging and featured a cable cam shot when the camera pulls back after Leonard walks to the corridor. “It’s the only moment I shot colour negative to turn into black-and-white because there was no way to hide anything in Carnegie Hall because we were pulling back, and looking at the ceiling,” says Libatique. “I bounced some lights for ambience right off screen, outside of the tilt up, and I had a light on a balcony off screen to give Bradley a little light so you can see him in the distance. Other than that, lighting fixtures were turned up as bright as possible.”

While Felicia and Leonard’s complicated relationship was a significant part of the story, the composer-conductor’s genius and talent also took centre stage at times. In certain sequences silhouette emphasised the musical master’s gift and powerful presence. “Bradley was unsure what he would look like conducting, so he had an early idea for the camera to spend time on Felicia and then you see his shadow move across from time to time,” says Libatique. “That idea turned into the shot in the movie – a giant silhouette that metaphorically takes over a life and Felicia is tiny in the frame. Everything’s about the size of the person in the frame, negative space and who’s filling it.”

For that scene the PRG Bad Boy moving fixture projected light onto Leonard as he stood on the platform conducting with a collection of High End Systems SolaHyBeam 3000s on Felicia to bring her out. “As the camera moved in, to avoid shadow, we used the light’s electronic blades to zero in so we could just keep moving forward. And then there was a crossfade between that light because eventually the blade covered it, so we started to dim that light and bring another light up to seamlessly get to her close-up.”

Following a fight between Felicia and Leonard, he pours his heart out in the powerful performance at Ely Cathedral when “the camera is almost intoxicated by the music,” says Libatique. “But the last shot of that sequence lands with Felicia over his shoulder, again conveying the idea that she is always present.”

Libatique often used moving lights because he likes to bounce light. “It doesn’t look like a mover scene, but in the big fight scene movers are above the set that I bounced in – one bouncing in behind the bed to the right and a couple hitting the windows to create more highlight,” he says. “I don’t necessarily point them at a face, but bounce them around the room because I can use their blades like ellipsoidal Source 4s. They weren’t just for the performance scenes, everywhere we put lights in the air, there were at least one or two movers.”

Searching for the shot

When directing, Cooper pinpoints the most important element in the scene and tailors the technique to suit. “It might be a long dolly push-in to Felicia when she’s sick and is talking to her two best friends, but we never cut to the friends until the end of the scene,” says Libatique. “It’s about putting the camera in a place that emphasises what’s important – searching for that one shot in the scene rather than six shots.”

The film opens with another significant and elaborately crafted sequence in which Leonard wakes up and receives a phone call asking him to take over from conductor Bruno Walter. A top shot then follows Leonard through various rooms and on to Carnegie Hall.

“The language for that first scene was in the script – it said ‘God POV’ – so Bradley wanted to show the moment Leonard gets that first important call and is pulled by God from an unnaturally high vantage point to his destiny,” says Libatique. “That high-angle repeats later with a top shot of Felicia that transitions into a top shot at the St. James, bringing us into a performance of On the Town.”

Achieving ambitious shots such as this initial sequence were possible working with a 45’ MovieBird crane and a Libra head. The bedroom was raised and the side and corner of the apartment and part of the ceiling were removed so the camera could be extended into the set. “As Leonard runs, he goes under the bed, down the stairs and the camera retracts and starts a dolly and swing around the hallway. Leonard goes underneath the frame and it transitions to the shot at Carnegie Hall,” explains Libatique.

The art department used Vectorworks to create pre vis for the scene, giving Libatique an idea of distance and allowing cameras to be placed on the pre vis set to view figures from different positions. “We all thought the shot would be perfect, staying with Leonard for every beat in the hallway. But there was one take where everything went wrong – the camera’s way ahead, and Lenny had to catch up,” says Libatique. “We thought for sure that was trash, and shot a few more but then Bradley watched the mistake take and said, ‘I think I like this one.’ At first we were horrified but watching it back, he’s right. That take in the movie really feels like God is pulling Leonard to his destiny.”

Among the crucial team members responsible for that sequence and many others were dolly grip John Mang and focus puller Aurelia Winborn. “Aurelia works in an improvisational and old school way,” says Libatique, “she’s always with the camera rather than at a monitor and is the last person I know to use a follow focus.”

Capturing the connection

With P. Scott Sakamoto SOC behind the lens as A camera operator and Colin Anderson SOC on B cam, Libatique operated the handheld work. “Scott and Colin have this filmmaking foundation Bradley loves. They work so hard to get the beats and shots, always being in the right place at the right time,” says Libatique. “Bradley had an instinct about how he wanted to shoot something and whether it should be handheld.”

Steadicam was used for much of the first half of the film, with handheld chosen for the East Hampton sequences. Crane and dolly shots featured throughout along with stationary dolly, while more specialised approaches such as remote head with jib set-ups, and Spidercam systems were selected for sequences such as Leonard looking over Carnegie Hall and the camera pushing him towards his debut performance.

For more dynamic shots, a variety of cranes were used such as the Scorpio 23’ and 30’ Technocrane, the Moviebird 35’/45’ Crane, and the Scorpio 45’ Technocrane. The cranes were paired with a versatile range of heads including the Scorpio Head, Libra Head, Matrix Head, and the Mo-Sys Head which was an essential piece of equipment throughout.

Rather than shotlisting and storyboarding, Cooper likes to focus on blocking and working with actors on set. “With him also being an actor, he has ideas, and is a very good listener and open to suggestions,” says Libatique. “He said he could see the lead role was really Felicia and what he wanted to communicate when playing Leonard was this love between them that would not go away. They were so connected and she understood who he was when she married him.”

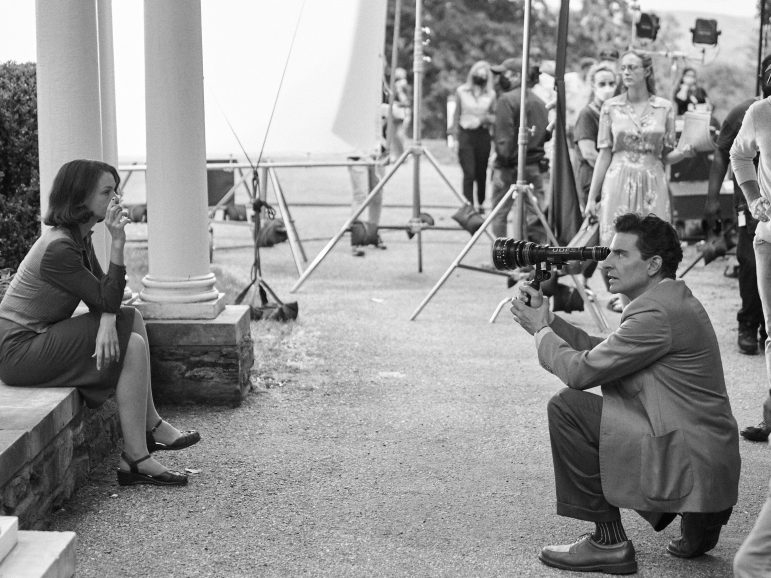

When capturing performances Libatique and the camera operators took cues from Cooper, needing to be nimble as the director was always attuned to the performers. One of Libatique’s favourite scenes demonstrating how Cooper informed the camera sees a lunch taking place outside a house in Tanglewood where Leonard introduces mentor conductor Serge Koussevitzky, and his friend, Aaron Copland to Felicia.

“They were off script the whole time and we were in a wide shot, a two shot, and another two shot until they got a rhythm,” he says. “Bradley gave them cues, they just kept talking, and the scene evolved and finally got back close to what was written. I’ve witnessed great technique from Bradley as a director when it comes to performance.”

Many sequences – including the opening scenes where Leonard wakes up in his apartment and opens the curtain, the Dakota apartment Leonard and Felicia spent Thanksgiving in and the party where Felicia catches Leonard being unfaithful – were shot at Steiner Studios in New York. Libatique commends production designer Kevin Thompson (Birdman, Ad Astra) for “making the sets fit into the reality of the film.”

Leonard’s apartment at the iconic Upper West Side building, the Dakota, had to be recreated on a stage and required meticulous research and a site visit to the apartment so Thompson could see the scale of the space and duplicate the mouldings and sizes of the windows. “We really tried to have key recognisable elements, especially with lighting, that would be nice little Easter eggs for people who wanted to look for them,” Thompson says.

Designing scenes for the monochrome section of the film required Thompson carefully select props and set elements that would be presented best in that medium. “Some colours might disappear or turn to black,” he says, so they began a laborious process where they would often photograph objects of set decoration, fabrics or wallpaper and then turn them into black-and-white to see how they translated.

Locations which Thompson painstakingly recreated included Leonard’s Connecticut and Manhattan residences. “In the case of the home in Connecticut, that was the actual house. It was remarkably close to the way it was when they lived there,” says Thompson. “We freshened things and made sure that it was for the right period.”

Significant scenes shot on location included performances at Carnegie Hall – a “phenomenal” experience the cinematographer treasures – and the fantasy sequence performance of On the Town at the St. James Theatre. “We shot in Tanglewood – a legendary place in the history of Leonard Bernstein and the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer home in the Berkshires. And most importantly, we shot at their family home in Fairfield, Connecticut,” says Libatique. “At first, I felt nervous about bringing equipment into the house and the grounds, but I soon felt this spirit of creativity and openness that surely came from the real Lenny and the Bernstein family.“

Some sequences were also shot at a house in Rye, New York, which doubled for the property in the Hamptons the family rented when Felicia got sick. Other important moments, including those of the family when Felicia is ill were captured differently, adopting handheld techniques. “We were very fluid about shooting the children, becoming documentarians in the scene and just letting it happen,” says Libatique.

Whatever the scene or setting, Cooper had laid a strong foundation to be able to perform the character as he also wanted his focus to be on directing and being brave with composition and coverage. “He’d be ready when we arrived, dressed and in makeup as Leonard, having spent six hours being transformed,” says Libatique. “But Bradley never wanted him being a performer to take away from him being a director.”

Cooper considers making a film about Leonard’s extraordinary life “one of the greatest joys” of his career and believes he has “never made art as fearlessly. His story forced me to be fearless, because he was,” he says. “That was the biggest gift that Lenny gave me.”