Here in British Cinematographer’s Hollywood bureau, we await our second Pfizer shot, while gearing up to attend – virtually, of course – the coming ASC and Oscar awards. Normally, this column would be reporting on how they were.

You will have been well-versed in the nominees by the time this runs, naturally, and it would seem Joshua James Richards, who is credited with both shooting and designing Nomadland for director Chloé Zhao – and is nominated for DP honours by the ASC, Academy, and the BAFTAs – is the frontrunner in those categories. The scrappy, well-lauded production has also given Zhao directing, writing, and editing nods. And given the film’s recent PGA win, the overall production stands as the Oscar favorite, too.

As for cinematographer nominations, the aforementioned Big Three in this category are mostly aligned in their picks (with the inevitable small variances): Newton Thomas Sigel ASC, nominated for Cherry (and not Da 5 Bloods) by the ASC, yields to Sean Bobbitt BSC’s work on Judas and the Black Messiah on the Oscar side, while the BAFTAs omit Phedon Papamichael ASC GSC’s lensing of The Trial of the Chicago 7, to instead include Alwin H. Küchler BSC and The Mauritanian.

Still, Papamichael, a previous Oscar nominee for Nebraska (though he’s had four earlier nods from the ASC, including Ford v Ferrari) was pretty tickled, releasing a statement calling the nod “an amazing surprise for me. I feel very honoured and want to thank all my collaborators in every department that have contributed to making this small gem a very special experience, and to Aaron Sorkin who collaborates in such a generous way!”

But let us also add a fourth to that “Big Three,” namely the Independent Spirit Awards, traditionally held in a tent on the beach, the afternoon of “Oscar eve.” This year, of course, it’s digital too. And to show how fuzzy borders can be between “studio” and “indie” now, Nomadland is a nominated favorite there, too, including for its cinematography.

But since we won’t be doing interviews in the adjacent press tent on said beach, we did talk in advance with one of Richards’ fellow nominees in the cinematography category, Jay Keitel, who shot She Dies Tomorrow for writer/director Amy Seimetz.

Keitel has “worked with Amy for 17 years now – I hired her as an actress on my thesis film at CalArts,” which he describes as a “futuristic Western” wherein “Ansel Adams-meets-John Ford.” His collaboration with Seimetz took them through the Starz’ series The Girlfriend Experience, which she co-created, based on the Steven Soderbergh film, and now they’re collaborating on a film that might be described as Soderbergh-meets-Ray Bradbury.

The film, at least, has an early Soderbergh feel (in terms of both a lot of self-reflection, and a certain type of “contagion”) while married to some of the notions in Bradbury’s early short story, The Last Night of the World, where people become convinced the world is ending. Here, the film explores the memetic quality of insisting your own life is at its end, without any evidence as to why, with the narrative passing from one character to another like something out of Bunuel’s The Phantom of Liberty.

The camera choices represented unusual combinations as well, as Keitel notes they started with a “Canon C300 Mark II to help with texture of the film – (it) gave more organic grain – then we used the ALEXA Mini. As we moved through the film, we very much played with texture.”

That playing also included an array of lenses, like the 58mm Clavius from Richard Gale Optics in the UK, which are rehoused Helios glass made in the former USSR, providing “shading and shadows in the highlights,” and an adjustable anamorphic bokeh, allowing more control of points of light in otherwise soft backgrounds.

Keitel also used uncoated ARRI ultra primes, which “have very interesting flair qualities, but overall, are sharper than the Clavius lenses,” and an Angenieux 28-70mm zoom, also uncoated, with its “stained glass flaring” – especially important when the titular “she” has a scene where she attempts to arrange for disposal of her upcoming remains – a lens he both loves and has “used for years and years.”

Then there was the 1000mm 75-pound special from Kelso rentals, originally manufactured by Clairmont Camera, which allowed him to shoot some desert scenes day-for-night. “I really love thinking about what shots in the movie can be day-for-night,” Keitel adds, but clearly, he loves thinking a lot about all the shots, and the best gear to capture them.

And thus, his nomination leads She Dies Tomorrow into the Indie Spirit arena. His situation is the inverse of cinematographer Daniël Bouquet’s, who shot the heavily Oscar-nominated Sound of Metal, even though his own work wasn’t in the six categories – including best picture and actor – that the film picked up.

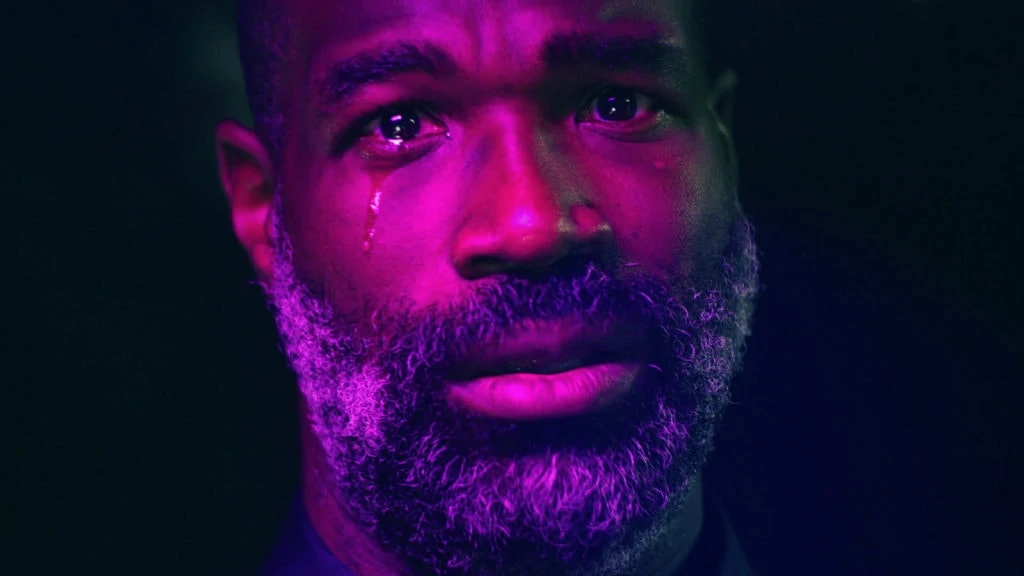

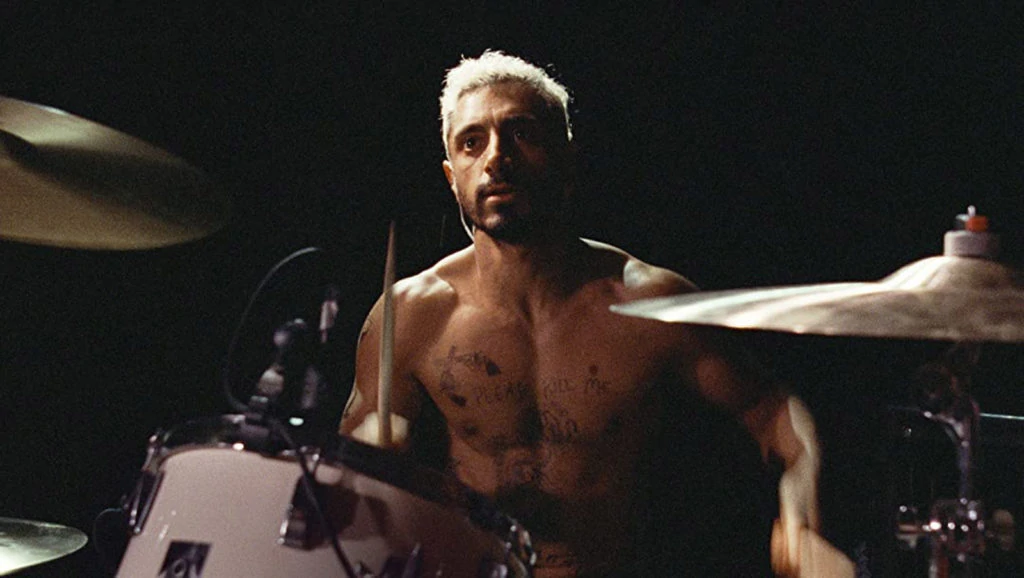

In part, this may have been because the story, about a punk-metal drummer, played by Riz Ahmed, who is losing his hearing and has to rethink his entire life, has been highly touted for its sound design, which helps take hearing audiences on the same journey into deafness that Ahmed’s character Ruben is experiencing.

Bouquet talks about working with nominated sound designer Nicolas Becker, saying he’d “never experienced such a professional pollination with a sound designer. We listened and spoke a lot about sound perspective, for Ruben, for the other characters and also for the audience. What do we hear when Ruben loses his hearing for the first time or doesn’t hear at all? And what do we hear when he sees someone else talking? We all expected a very rich and dynamic sound design and I felt I needed to visually make space for that, by keeping the imagery more sober, so that the sound could change perspective within the same framing.”

That imagery, meanwhile, was captured on 2 perf 35mm film, and Bouquet says that he and director Darius Marder, himself nominated, along with his co-writers, in the original screenplay category, wanted to use “as few lenses as possible” deciding on a “slightly longer lens to help isolate Ruben into his sound perspective.”

His gear choice was unusual though, as he “was happy to discover I could sub-rent the Aaton Penelope from a camera friend in LA. I knew the camera from previous projects in Europe. It’s a very flexible and compact, quiet sync-sound system. Perfect for these conditions.”

The Penelope also straddles aesthetic and technological eras in cinematography, being a 35mm camera with a scan video-tap that can also provide a 4K digital output. This was paired with Sigma lenses which Bouquet describes as “light weight, have nice fall off, (and) very close-focus and… are affordable.”

“It was such a great pleasure,” he says, “to have the opportunity to go back to that pretty elementary way of working. It was definitely not documentary, but we worked very intuitively and improvised where we could.” In the manner, perhaps, of musicians also on top of their crafts.

It was such a great pleasure to have the opportunity to go back to that pretty elementary way of working. It was definitely not documentary, but we worked very intuitively and improvised where we could.

Cinematographer Daniël Bouquet

Meanwhile, even in the swirl of awards season, other new films are getting released, some even with tentative, partial theatre audiences to see them – though all indications are that streaming will play an even larger part in release strategies than it did, pre-pandemic.

And while the horror genre has already been addressing pandemic-based stories for years, one newer theme is that of ethnic, or race-based trauma – horror deriving from persecution simply because someone belonged to a certain group, faith, looks a certain way, etc.

Get Out kicked off the current renaissance of what, sadly, has become an increasingly timely sub-sub-genre. On the publishing side (between columns, your correspondent has done some storytelling in this genre himself), there are books like Stephen Graham Jones’ The Only Good Indians, with similar explorations.

And currently available on VOD, in the also-growing sub-genre of Jewish-themed horror, a culture already replete with stories of golems, ghostly dybbuks, and more, comes The Vigil, where a young man in Brooklyn, attempting to leave a Hasidic, Orthodox practice (after a trauma of his own) to more fully enter the modern world, takes a job among his old haunts (literally, as it will turn out), to act as a shomer, a “watcher” who stands vigil over the body of the recently dead, to make sure the soul can depart with as few complications as possible.

Needless to say, complications ensue.

Cinematographer Zach Kuperstein was brought on by writer/director Keith Thomas, after admiring his also disturbingly effective work in an earlier indie horror film, The Eyes of My Mother.

“At the time,” Kuperstein smilingly recalls, “I was trying to not become the horror guy,” but Thomas, who had “studied at Rabbinical school (and) studies the Talmud and Torah extensively, discovered the mazzik,” a particular type of demon who “feasts on guilt,” as he terms it, and can remain “attached” for the rest of a person’s life.

Thus, the soul of the departed isn’t the only presence the shomer has to contend with.

Kuperstein shot the intense, primarily single-set character study, with actor Dave Davis anchoring most of the film, on what he terms a “normal Alexa,” but with two sets of lenses, to establish differences when Davis crosses from what we might call the “agreed-upon” world, into his long night with the mazzik.

There were also two styles of camera moves, too, “maintaining a sense of the moving camera until we get to the house,” at which point, a certain brimming quietude sets in.

As for the glass, he deployed Atlas Orion anamorphics “for the opening sequence,” then switched to Japanese-made Kowa lenses, which he said had the “opposite effect” of the Orions, “convex at the edges, (and) it expands and contracts as the camera moves.”

He was able to look “at other people’s tests online – you can bring up the videos at different focal lengths,” and thus was able to save a considerable amount of time in his three weeks of prep, leading to an even more compressed “eighteen shooting days.”

Making effective use of those shooting days was helped considerably by his crew, which Kuperstein says “he loves to pieces,” and include gaffer Joel Kingsbury, key grip Paul Wallace, 1st AC Logan Gee, and Steadicam operator Brendan Poutier.

Among their improvisations was using a glass casserole dish, borrowed from a nearby church (where crew lunch was served, after using the grounds for a location) with “the curvature of the glass (making) distortion effects,” when the mazzik shows up.

They “worked in that curvature to get it working just right,” even taking the anamorphic lens off the mount at one point, making for a “gut-wrenching moment, hopefully.”

But of course, the world has had many of those this past year. As for Kuperstein, he’s spent his downtime – with The Vigil’s release continually delayed – ‘inventing something. An accessory for use on film sets – I own the patent for it.”

We will, of course, keep readers updated when said unnamed device makes its appearance, though the inventive Kuperstein adds that he’s “learned a lot from the last year.”

It remains to be seen who else has learned anything from this past year, and thus, the market for topical horror will doubtless be with us for some time.

And speaking of delays, we’ll be doing our awards show roundup at last, next month!

Until then, avoid the mazzikim. And write us: @TricksterInk, AcrossthePondBC@gmail.com