THE MAN, THE MUSIC, THE LEGEND

Telling the extraordinary life story of a legendary figure such as the king of rock ‘n’ roll is no small feat. Through meticulous research and using character dynamics and the drama of the script to drive the lensing, cinematographer Mandy Walker AM ASC ACS and director Baz Luhrmann crafted a biopic bursting with star quality.

“Once Baz gets on set, he’s like a conductor. He’s discussing the emotional resonance created by every aspect of capturing an image, for example calling focus pulls with the focus puller, walking next to the crane to set the speed and call the moments of rise and fall, and gesturing during a take to the gaffer and dimmer board operator about important lighting changes,” says Mandy Walker AM ASC ACS about teaming up for a fourth time with writer-director Baz Luhrmann.

Their latest sparkling production – the biopic Elvis – tells the legendary life story of rock ‘n’ roll royalty, Elvis Presley. When Walker joined the team in July 2019, Luhrmann was as well researched as always, came prepared with a type of look-book of historical references and preliminary designs he and Catherine Martin (the production and costume designer, and also Baz’s wife) had produced, and talked through the historical footage he had gathered after 10 years of research.

“He shared the general story outline for the film before the script had been written. There was a vast amount of historical footage documenting Elvis’s life and his influence on music and American history for us to refer to. So, I went away to continue researching and exploring the incredible footage as well as images and inspiration for the visual storytelling I could offer up,” she says.

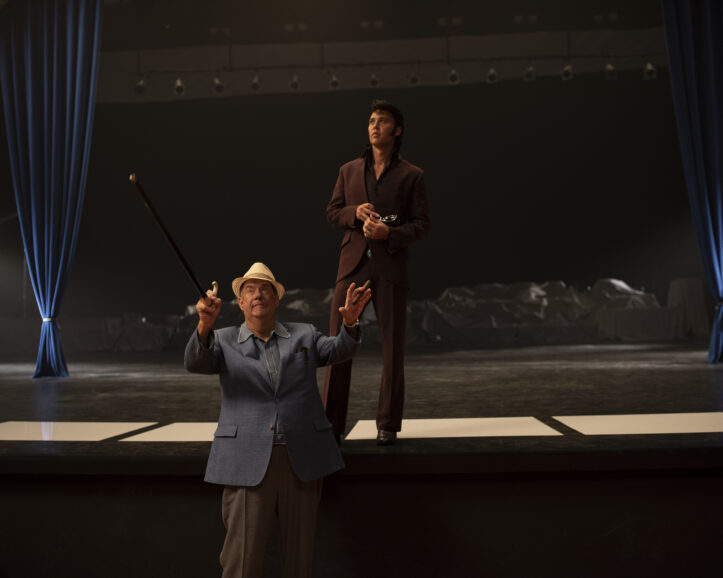

As well as feeling honoured to make a film about such a significant figure in history, Walker was excited to “bring the music and the drama of the story to the screen”, taking audiences on a journey through multiple periods in the star’s life as well as his experiences with manager Colonel Tom Parker, played by Tom Hanks. It was important to achieve this in a way “that both a young audience who didn’t grow up through this period of culture and music, and for an older audience of Elvis fans could relate to.”

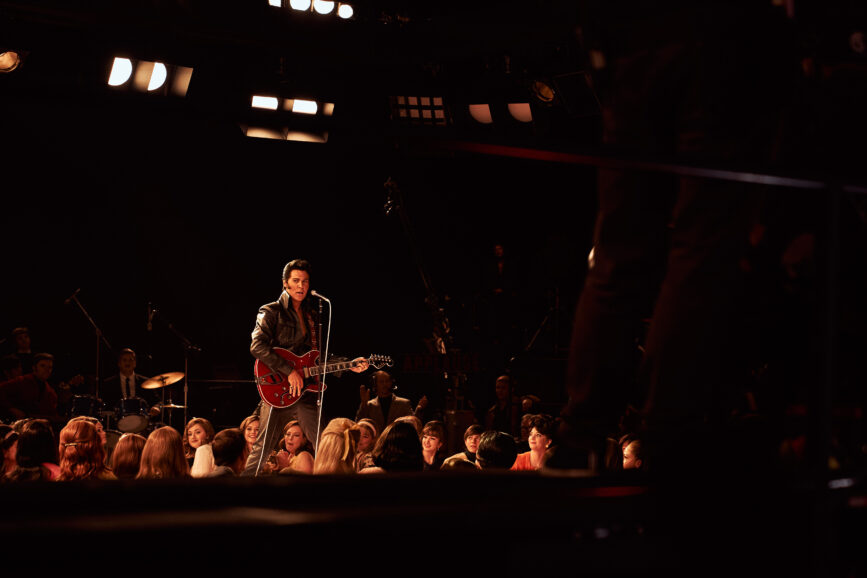

Luhrmann referred to the specific archive footage and stills from throughout Elvis’s phenomenal life and career which would be replicated by the filmmakers shot for shot as “trainspotting sequences”. These included the 1956 Russwood Park concert in Memphis – documented by photographers such as Alfred Wertheimer with his stills and 16mm black-and-white footage – and an iconic hour-long broadcast known as the NBC ‘68 Comeback Special and the first show in the Hilton Ballroom in Las Vegas.

Meticulously testing every element in unison has been essential to the success of Luhrmann’s productions, ensuring every department is on the same page from inception to create a visual language that flows throughout the movie. As always, Luhrmann gathered all the departments together during pre-production and shot meticulous tests with set pieces, costumes, lighting, make-up, and hair. They then studied the references thoroughly during pre-production before spending weeks plotting the camera set ups on the sets as well as with the camera department, lighting crew, and dimmer board operators to ensure when the historical events were captured, they were replicated accurately on screen.

Walker admits the 16-week prep period was lengthy, but “thinks it was the right amount of time to study the ‘trainspotting’ footage, study and talk about the many sets, shoot various tests for colours, textures, and costumes, and share ideas back and forth with production designers Catherine Martin and Karen Murphy to unite all the elements when creating Elvis’s world. We even worked out what length lenses they were using on the existing footage and placed the cameras in the exact same positions with our camera package.”

The dynamics between characters and drama within the script also influenced the way Walker approached her lensing. “For example, in the ’68 Special scenes, these sequences were also about Priscilla’s connection with and reaction to Elvis as she watched him perform and also the Colonel’s connection as he watched on from the control booth,” she says.

Lensing a life story

Having thoroughly explored the references and historical significance of Elvis’s life, Walker and Luhrmann visited lens specialist Dan Sasaki at Panavision, to further immerse themselves in the storytelling. Discussions led them to shoot spherical 65mm on Panavision Sphero lenses for the first part of Elvis’s life, from growing up in Memphis though to his time in Hollywood.

“Dan always creates a few iterations of the bespoke lenses. When we tested the first iteration of the Spheros it didn’t give us quite the feel we wanted for the different periods, so he detuned them a little, so they weren’t perfectly sharp, and looked much more relatable to the time period,” says Walker.

To capture the Vegas period of Elvis’s life, Walker switched to anamorphic, using the 1.8 squeezed Panavision T Series lenses. Sasaki also increased the contrast, saturation, and altered the colour of the flares. “I didn’t want just blue horizontal flares as I feel that’s a very modern look,” says Walker. “The film had to look like it was shot in the ‘70s rather than in the 2000s. Dan added different colours in the flares, so they also featured magenta, green, and a little bit of yellow.”

Walker used no filtration, achieving the desired look through the lenses alone. A Petzval lens captured some flashbacks, dream-like sequences, scenes of Elvis passing out after taking drugs, and some montage segments to “draw your eye into the centre of the frame and create a vortex vision.”

The way Walker approached colour evolved for the Vegas sequences, working with different LUTs for each period. “Baz and I worked with a great DIT, Sam Winzar on set to create our LUTs. Sam and I would go into dailies every night to make sure the historical transitions were balanced and the LUT was in line with our reference. The look of the final film didn’t change much from what we initially planned and determined at that stage of the process.”

The main elements requiring treatment in the grade – working with colourist Kim Bjørge on Australia’s Gold Coast – were some montage scenes and those integrating older footage with digitally captured sequences. When Walker did her final pass, visual effects, production designer Martin, and Luhrmann also oversaw the process. And as Bjørge was also the dailies colourist, he “already knew the film and images incredibly well, meaning he started from a great base when it came to the final grade.”

Walker and the crew shot 360 degrees, enhancing the sets through visual effects when needed. The team, headed up by VFX supervisor Tom Wood, extended the Beale Street environment, adding blocks in the distance. In concert sequences, such as those taking place in Vegas, the first third of the audience were captured in camera with the rest of the crowd added in visual effects.

“Shooting scenes of the MGM backlot on stage required the sky to be extended. So, I would sit with Baz and Tom and pick a sky and weather conditions, and then tell Tom where the sun was coming from and light to that as a reference point,” says Walker. “It was a similar process for the exterior of Lauderdale Courts – where Elvis lives with his family before they move to Graceland. We built one wall of that building, but then the scene where Elvis walks down the street was an extension of the set created in visual effects.”

Building a believable world

Like many recent productions, Elvis did not escape the pandemic disruption. Principal photography began at the end of 2019 before shutting down when Tom Hanks (Colonel Tom Parker) caught COVID. Production then resumed at the end of 2020, with shooting taking place across Australia and at two backlots 30 minutes’ drive from the Village Roadshow stages. The exterior of the iconic Graceland where Elvis lived with his family and Priscilla was built at one of the backlots, with four blocks of Beale Street, another significant location and influence in Elvis’s life and music, constructed at the other.

“It was tricky finding the Graceland location because we needed to create the façade of the building as well as an environment that matched the early days of Graceland. Beale Street needed to adopt a very clean palette because the streets were going to be extended in visual effects. It also needed to offer enough room for cars to be driven around the blocks and be shot against blue screen,” says Walker.

Everything else captured was shot on stage, including the sequences at Club Handy in Beale Street where Elvis performed during the early years. As all sets were being built Luhrmann, Walker, and key members of the crew spent extensive periods walking around and plotting how they would shoot the various stages of the star’s life.

“The NBC ‘68 Special and Vegas showroom were the biggest set-ups for me. I had to study the existing footage and documentary footage to examine the lighting with gaffer Shaun Conway. The songs we shot of his Vegas show, are lit in exactly the same way as the original performances, even down to the colour palette on the backdrop and all the lighting cues,” says Walker. “It took a lot of precision in the planning, but it pays off when you watch the footage. It also helps that Austin Butler was so amazing in his role as Elvis, and the performance is identical.”

Elvis marks Walker and gaffer Shaun Conway’s sixth production collaboration, having “grown up together in the Australian film industry” after making their first movie together, The Well, 25 years ago. “Shaun is so passionate about lighting and storytelling and is very involved in the discussions with Baz too,” says Walker.

Lighting the different stages of Elvis’s life and significant locations that featured required a combination of sources old and new. Predominantly LED fixtures were used to light the dramatic sequences with more traditional lighting that was in shot illuminating the concert scenes mixed with LED out of shot. “We worked with a lot of old Fresnel lighting in the 68 Special after studying what they did use in the TV studio, as well as adapting some LED lighting to fit in including ARRI SkyPanel S60s which we put in boxes, so they resembled the small soft boxes used at the time.”

PAR Cans were also selected for the concert sequences along with ARRI Orbiters to “create a PAR Can look because they could offer a similar quality, but much more exposure and colour control. What appeared in the frame was almost always old-fashioned real concert lights and Fresnel lights from the period, while LED lighting was off camera.” Moving Martin MAC Viper lights also featured onstage, creating a spotlight which would allow the colour and angle to be quickly changed.

Creating authentic moments

For the early part of Elvis’s life, references for tone and colour included the work of photographers such as Gordon Parks and Saul Leiter, and Elvis’s family photos and home movies. Walker and Luhrmann referred to the way these early parts of the musician’s life are captured in the film as “black-and-white colour which has a very limited palette and is a little desaturated” but which also has a similar contrast to images from that period.

“By the time we got to the sequences during his time in Hollywood, it was more of a Kodachrome look – more contrast with a little deeper depth of field, and different lighting and framing choices,” adds Walker. “For the later Vegas scenes, we switched to anamorphic colour, more saturation, and anamorphic flares. We also represented that time in the ‘70s using lenses from the ‘70s.”

The filmmakers decided to adopt a 2.40:1 aspect ratio for the whole film. “Once we were shooting anamorphic, we were at 2.40 so we then shot spherical 2.40:1 too. It was just about changing the feeling of the lenses and of the approach to composition and camera movement,” says Walker.

Very early discussions also explored whether shooting on film or adopting digital capture was most appropriate for the biopic. Ultimately, they felt they “could shoot digitally and still create authentic moments through the lensing and LUTs,” using the ARRI Alexa 65 provided by ARRI Rental for the majority of the film and the Alexa LF to capture some of the high-speed footage. Live grain was also added to certain scenes to match the archive footage.

“We believed we were starting with a palette we could be totally in control of using digital. As it’s an epic tale and Elvis’s experiences were larger than life, we thought why not go to an epic scale of photography using 65mm. I love the way it captures landscapes and wide shots as grand, but close-ups are very intimate, in turn adding to the drama.”

Camera movement was used more gracefully for the scenes in Tupelo and Memphis but when the story moved on to Vegas – when Elvis was performing hundreds of dates in a year – “more rapid and spinning camera movement was adopted to enhance the craziness of the situation.”

Hardly any handheld features; it is only used for specific sequences including when Elvis is attacked on stage in Vegas and to depict some aspects of his personal life and when he is intoxicated. The use of the camera always pertained to “the fast-paced and frantic period when his life was getting more out of control.”

Walker highlights that overall, the camera was controlled throughout the many pertinent drama sequences, partly because “Baz is always in control of the way the camera moves to the rhythm of the drama and performance. When it does move, there’s a reason for it.”

Composition and framing related to the images the filmmakers had seen depicting the period the story would unfold in, from the more formal and composed style adopted to shoot the early concert sequences at The Hayride – where the Colonel first spots Elvis performing as a charismatic vision in a pink suit – through to Russwood which featured more extreme contrast and was documented using more vigorous camera movement.

“That was especially true in the part of that concert where Elvis was pulled off stage and he couldn’t see his mother because she was dragged into another car,” says Walker. “We moved the camera in a more frantic manner and shot that on long lenses, with foreground people obscuring the view, and adding to the chaos of the moment by the camera flashes going off and girls crowding around his car. I was always conscious of replicating those historical moments people are familiar with but also capturing the drama.”

For around 90% of the shoot three cameras were rolling, occasionally using four or five to capture the concert sequences. Walker operated occasionally but as she had to oversee the vast number of cameras, standing with Luhrmann at the monitors discussing each shot, it was impractical to operate extensively.

The cinematographer was delighted to once again be working with a “talented camera team” to capture footage of a standard that would convey the king of rock ‘n’ roll’s phenomenal story. This included A Cam and Steadicam operator Jason Ellson and B Cam operator Jay Torta who shot splinter unit additional photography, both long term collaborators of Walkers.

“We have an excellent shorthand which really helped,” she says. “Even though this project doesn’t look like anything I’ve done before, working with people who already understand the way you communicate and collaborate creates harmony in the visual language.”

Working with key grip Greg Tidman and his team for the first time but with frequent collaborator dolly grip Brett Mc Dowell who Luhrmann also has a long working relationship with, and in close collaboration with Luhrmann, two Scorpio Technocrane systems (a 45ft and a 23ft), with Matrix heads were used to offer flexibility when capturing shots of the concert sequences. Luhrmann and Walker’s team also built smaller fixed cranes for the more intimate locations to shoot scenes such as when Elvis is writing in his dressing room.

Efficiency and education

Listening to the music Elvis created was imperative for Walker and the crew to triumphantly translate the story in cinematic form. “Baz had already recorded some of the music that was going to be added in post-production, so we would listen to that to help create the emotion of the scene,” says Walker. “We had it on set, obviously, but in the rehearsals, it was so useful to work out how to move the camera and the lighting cues in line with the music, and to determine how it would be used to create drama and emotion in the scenes. This was something I hadn’t done to that extent before, and it was a wonderful experience.”

When shooting the footage that was to be incorporated into the split screen sequences peppered throughout the film, Luhrmann was once again well-prepared and had already gathered most of the archive footage that would feature alongside it.

Walker considers Luhrmann a “visionary and a director unlike any other” she has worked with. Each collaboration is a learning experience as he always shares an abundance of knowledge. On this occasion Walker advocated for the importance of efficiency when lighting 360 degrees. “It gives the director even more flexibility of time with the actors. The faster I can swing around from one side to the other, and the more prepared I am, the better it is for the day to keep up the momentum.

“I learned that from Baz because he is so well prepared and would know exactly what we were aiming to achieve at all times. However, he also left room for change. Sometimes we’d be on set and things would develop and he wanted the freedom to enhance and adapt to ensure the most authentic and immersive story is told. Baz was once again such a great collaborator and communicator throughout, making everyone feel involved in the day-to day creation of the life story of Elvis and the effect he had during these periods of American culture.”